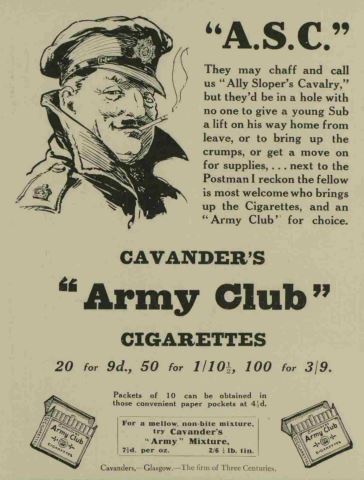

The men of the Army Service Corps (ASC) were jokingly referred to as Ally Sloper’s Cavalry, after the scruffy, vulgar, gin-swilling loafer Victorian comic strip superstar famous for sloping off down the alley to avoid the rent collector. It was a good choice – the men in its ranks needed the same cheerful disregard for danger as they ducked and dived around the fighting soldiers,

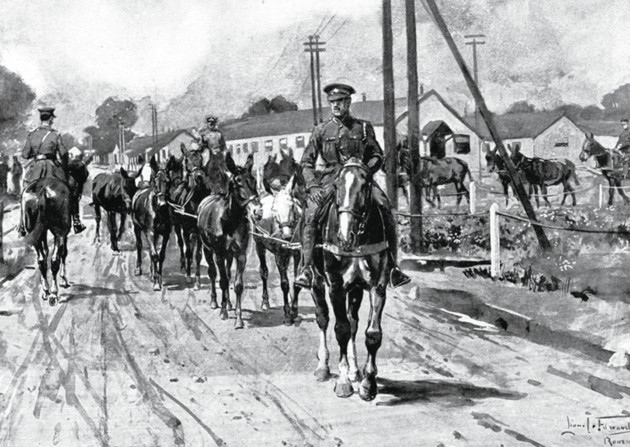

Soldiers can not fight without food, equipment and ammunition and during the Great War, they could not move without horses or vehicles. It was the job of the ASC to provide them. In the Great War, the vast majority of the supply, maintaining a vast army on many fronts, was supplied from Britain. Using horsed and motor vehicles, railways and waterways, the ASC performed prodigious feats of logistics and were one of the great strengths of organisation by which the war was won.

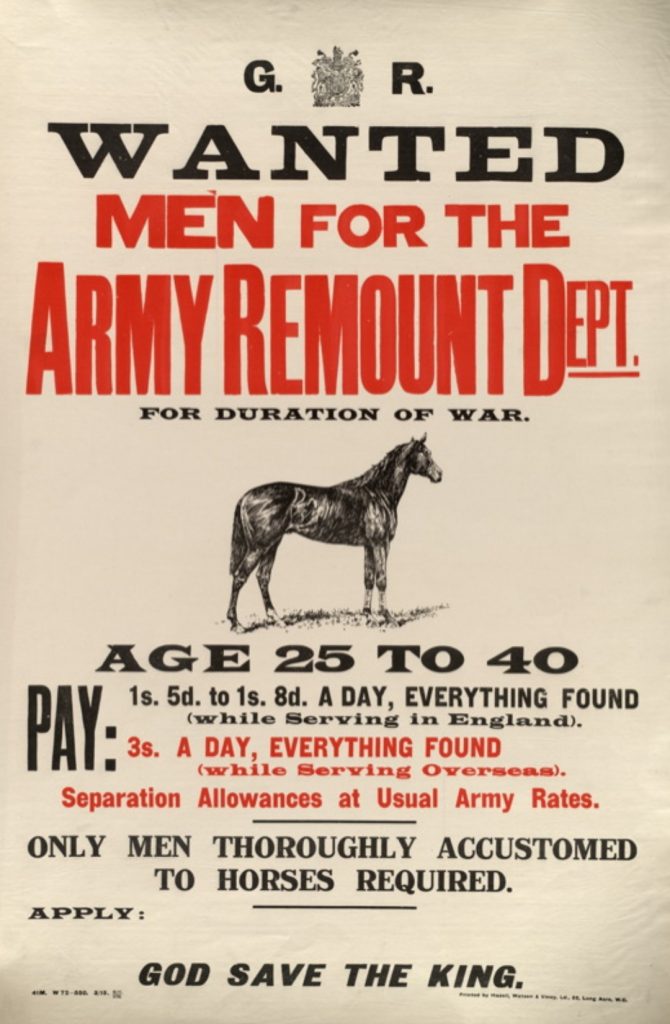

A Remount Squadron consisted of approximately 200 soldiers, who obtained and trained 500 horses. The soldiers of the Remount Depots were generally older, experienced soldiers.

The Central Remount Depot was based at Aldershot with additional Remount Depots (No.1 at Dublin, No.2 at Woolwich, No.3 at Melton Mowbray and No.4 at Arborfield).

The acquisition of horses for the war effort was an enormous operation. In his book, The horse and the war, Sidney Galtrey states that 165,000 horses were ‘impressed’ by the Army in the first twelve days of the war alone. Records show that during the course of the war some 468,000 horses were purchased in the UK and a further 618,000 in North America.

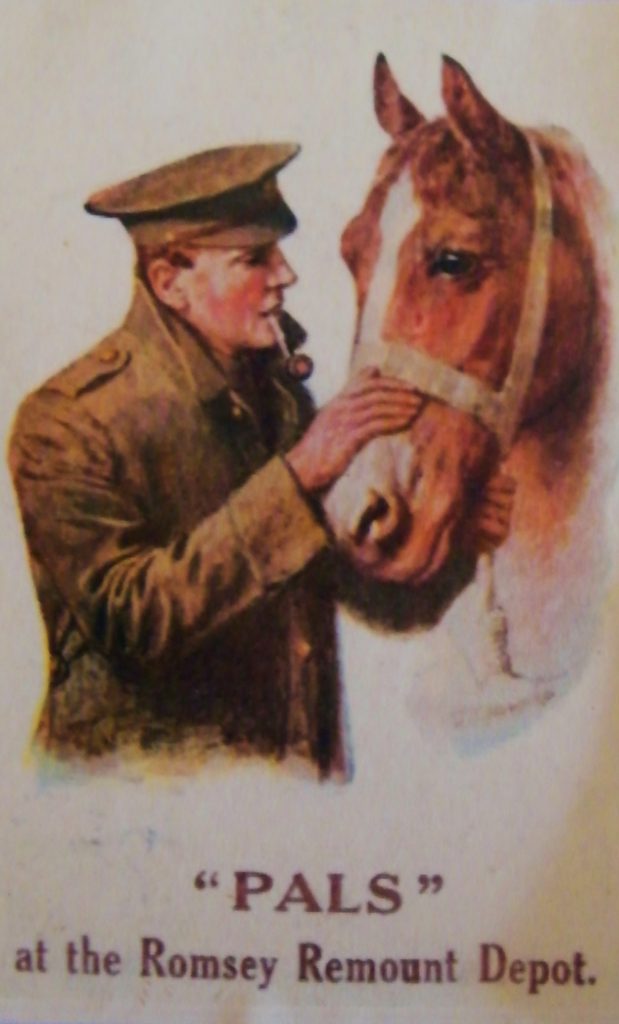

This massive increase in numbers required a rapid expansion of the Remount Service. Four additional main Remount Depots were established at the following locations:– Shirehampton (for horses received at Avonmouth), Romsey (for Southampton), Ormskirk (for Liverpool) (depot situated at Lathom Park) and Swaythling (a collecting centre for horses trained at the other three centres for onward shipment overseas).

As you wander around Thorpe Road cemetery in Melton Mowbray, you will see the familiar gleaming white Portland stone grave markers/headstones. Standing proudly above the graves of military personnel, they mark the graves of those who had died whilst serving their country, some through enemy action but the majority through accidents. Some are in tended plots whilst others are scattered and isolated. This is no different to the other war graves throughout the UK.

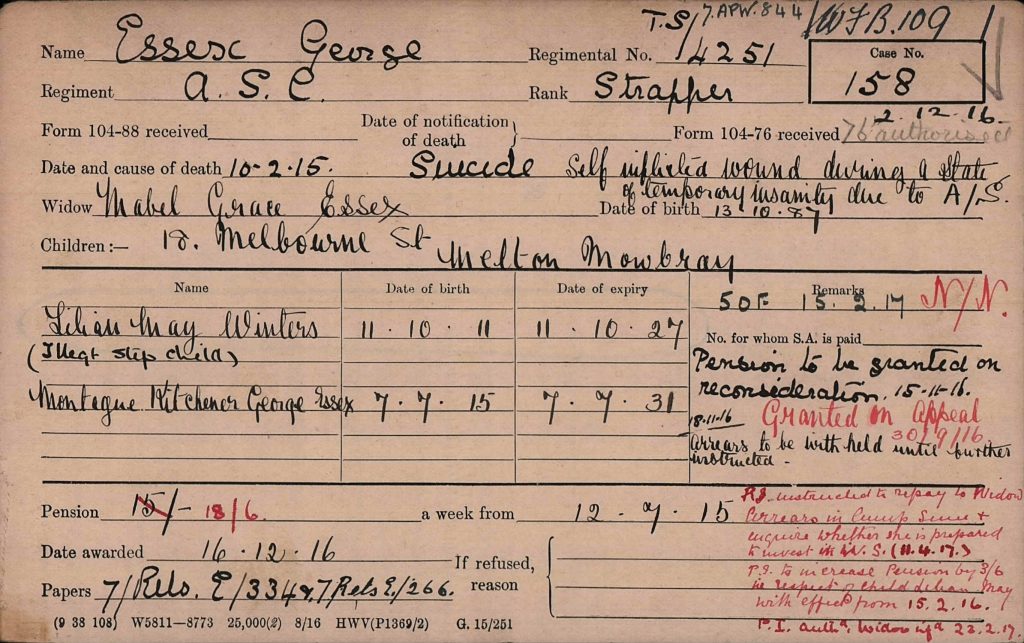

One of the scattered war graves is that of an Ally Sloper – Strapper George Essex, Service Number TS/4251 of the Army Service Corps who died 10th February 1915. The TS prefix to his service number means that George was specially enlisted for his trade: in other words, he came from civilian employment in a trade that was of direct value to work in the Horse Transport.

A Strapper is the same rank as a Private and is essentially a groom working with horses. This is certainly no surprise seeing as there is an Army Remount depot in Melton.

There are, however, a couple of anomalies:

Firstly, the inscription on the headstone shows his unit as the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) and the Regimental badge displayed on the headstone is also of the RASC. George died in 1915 and the Army Service Corps was not giving the Royal assent until 1919 by the King in recognition of its efforts during WW1.

Admittedly, the CWGC casualty record does display his unit correctly as the Army Service Corps (ASC). They are aware of this error and when the headstone is replaced, the correct Regimental crest will be engraved on the new stone.

Secondly, according to his casualty record on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, he was the husband of M.G. Essex of 13 New Street, Melton Mowbray. As a serving soldier from Melton that has died whilst serving their country, you would expect to find his name on the towns war memorial. Unfortunately, this is not the case, so why does George Essex not appear on any of Melton’s war memorials?

Let’s take a look at who George Essex was.

George was born 1878 to William Essex and his wife Fanny (nee Draper). He was baptised on 11th August 1878 by Reverend William Colles. According to the 1881 census, William was a brick labourer and George was the middle child, with an elder sister, Esther, and a younger sister, Fanny.

In 1889, Georges mother Fanny died, and William later re-married in 1892 to Ellen Wooding.

By the time of the 1901 census, William had become and engine driver, George was a bricklayer labourer and there was now Elizabeth and William in the family.

At the time of the 1911 census, the Essex family were living at 4 Bentley Street. Georges’ father, William, had passed away, Ellen was the head of the household as a widow. George was listed as aged 32, single and his occupation was a Furnaceman (Labourer).

George married Mabel Grace Winters on the 21st March 1914 at the Register Office. When they got married, Mabel already had an illegitimate child, Lillian May Winters. The family made their home in a small three bedroomed house, not far from the centre of town at No.5 Bentley Square, Melton Mowbray.

When the 1911 Census was taken, Mabel was residing at No 9 Wilton Terrace with her sister Violet Pearson, her husband Alfred Pearson and their daughter Zara.

Mabel’s daughter, Lillian May was born 11th October 1911 and the birth certificate listed her address and occupation as 24 Scalford Road, Melton, a Doubler in a Spinning Mill. The birth certificate did not name the father, consequently it is unknown as to whether Lillian is the child of George.

As soon as war was declared, George started working as a civilian Groom at the Melton Remount Depot. He subsequently enlisted into the Army on the 5th November 1914.

According to his attestation papers, he was aged 36 years and 158 days and his height was listed as 5ft 5in. His occupation was listed as Groom and his answer to Question 15, “Are you willing to be enlisted for General Service?” was “Yes Remount Depot Only”.

Shortly after enlisting, George was transferred from the Melton Depot and attached to the Romsey Depot to help train horses being received in Southampton following purchase in the USA.

George had been home on leave since Friday 5th February 1915. Prior to that, he had been hospitalised for about a month with injuries to his leg following being kicked by a horse he was training.

The Essex’s neighbour, Mrs Mary Cox, husband of Charles Cox at No. 3 Bentley Square believed George had got home late on the evening of Friday the 5th. She saw George on Saturday morning and she asked him how he was getting on. He told her “quite well” and how kind the people at Southampton and the other various depots were.

According to Mrs Cox, she said he seemed to be himself but she noticed a ‘sort of wildness’ in his eyes. She had also seen him on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday and he still had a ‘glassy’ excited look in his eyes. She knew he had been in hospital for about a month with his leg and he had been to France and back since he came out of hospital.

Mrs Cox believed that George was going to be returning to camp on the Wednesday as his wife Mabel had got in some provisions that he usually took back with him.

On Tuesday evening, George and Mabel retired to bed at about ten o’clock. About half-past six the following morning, Mabel heard George get out of bed, and asked him where was going? He said was going downstairs for a “fag” and went and returned immediately.

The next moment George struck Mabel on the head with a hammer that he had brought upstairs with him. She struggled with her husband, and, though he succeeded striking her about the head three or four more times, twice on the stairs whilst she was endeavouring to escape, none of the blows were of sufficient force bring her down.

It was about twenty to seven when a Mr Carlton was walking home from his night shift at the Holwell Iron Works and saw Mabel stood on her front doorstep in her night clothes. Her hair was matted with blood and her nightclothes were covered in blood from the injuries sustained from the hammer blows.

Mr Carlton got the attention of the Cox family, next door at No.3 and Mary Cox asked Mabel “What the matter?” she replied, “Oh my baby, never mind me, my baby”. The Cox’s eldest son, pushed by her and went upstairs and grabbed the child, brought her downstairs and put herein her mother’s arms.

As the son went upstairs, Mary Cox saw George sat at the kitchen table. When she said to him “George what have you done?” she noticed a wound in his neck from which blood was flowing and as he tried to speak, he could not and only turned his eyes. George walked around the kitchen table and collapsed on the hearth rug in front of the fire.

When Superintendent Hinton of Melton Police spoke to Mary Cox, he asked “Have you heard of any previous quarrel between the man and his wife?” the response was “No Sir, They have come into my shop together and have always seemed a comfortable pair.

The questions continued: “Was he a steady man, as far as you know?” Mary Cox replied “Yes, he had been a teetotaller for months, in fact, years.”

“Do you think he was jealous of his wife?” Mary again replied “No, I don’t think so. There is always one or two mischief makers who try to upset things, but I don’t believe the man was naturally jealous. He always spoke respectfully of his wife. There might have been a little trouble some months ago, but it was only hearsay, as far as she was concerned, and she did not take any notice of that.”

Dr. J T Tibbles examined the body of George Essex. He found him lying on the hearth rug, lying prone on his face and his feet towards the window. The Doctor could feel no pulse and pronounced him dead. He had a large wound in the neck, from beneath the left angle of the jaw right across the front of the throat to a point below the right of the jaw.

The wound and consequent loss of blood was sufficient to account for death. From the nature and direction of the wound he had no doubt that it was self-inflicted. On a chest of drawers Dr Tibbles saw a razor, it was open, and covered with blood stains. The actual cause of death was syncope from the loss of blood.

At the inquest, George’s sister, Sarah Pick stated that about fortnight ago she received a letter from George, which Mrs. Essex saw, and which she afterwards ascertained she had destroyed.

George wrote asking her to keep an eye on his wife. On a previous occasion when he came home on leave, he had said to Mabel that he knew about her as the talk was all over town. Sarah told him she had heard things, but he must not take notice of what people said, as possibly they made more of it than there was. He replied, “Well, seeing is believing, and if I hear any more you will not see me again.” She then asked him if he meant to keep away, and he nodded his head.

He was certainly very troubled about his wife and was very fond of her, but he thought she was going on in a different way from what she ought, and it preyed on his mind.

The incident was reported in the local press, the Melton Mowbray Mercury and Oakham and Uppingham News. It was also published in other newspapers around the country such as Manchester Evening News, Birmingham Mail, Nottingham Journal, Nottingham Evening Post, Leicester Daily Post, Leicester Chronicle, Coventry Standard and Grantham Journal.

The verdict of suicide could well explain why George is not listed on any of the towns war memorials. There was no strict rule as to who was included on the war memorial or excluded from it. The list of names to be added to the memorials was approved by local committees and quite often, those service personnel who committed suicide were excluded.

Back in 2013, Princess Anne unveiled a new War Horse permanent memorial to commemorate the thousands of horses shipped into battle during WWI have unveiled a bronze model of their statue. Click here for more info.

About 120,000 of the 1.3 million horses and mules involved in the conflict passed through a giant military depot just outside Romsey in Hampshire.

Not everyone that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorate was killed by enemy fire. Consequently, all serving military personnel who died during the First or Second World War, irrespective of the cause or circumstances of their death are commemorated with a headstone where the burial location is known, hence why George has one of the familiar war grave headstones on his grave.

It would appear that around the time that George enlisted into the Army, his wife Mabel had fallen pregnant. Mabel gave birth to a baby boy on 7th July 1915. Tragically George and his new born son, Montague Kitchener George Essex never got to meet each other.

In August 1915, Mabel was informed by the Colonel IC Army Service Corps Records that in view of the circumstances of the death of her husband, a pension for herself and child can not be granted from Army Funds.

Following an appeal, the War Office confirmed that “it has been decided that the widow of No TS/4251 Strapper George Essex, Army Service Corps, may be regarded as eligible under the usual conditions for the grant of a pension from Army Funds”.

According to the pension record card, the amount awarded was 18/6 a week from 1th July 15. Following the successful appeal, the Army were instructed to pay the arrears as a lump sum and to make enquiries as to whether Mabel would like to invest the money into the War Savings scheme.

On 17th July 1919, the War Office issued a list of service personnel who had died on Active Service (A/S) and whose next of kin were to be issued with the Memorial Plaque, commonly referred to as the ‘Death Penny’ and Commemorative Scroll, the list contained the details of TS/4251 Strapper George Essex.

However, the Colonel IC RASC Records at Woolwich queried this in a letter dated 20th September 1919 asking the Secretary of the War Office as to whether the circumstances in which George died should debar the next-of-kin from receiving the plaque and scroll. On the 5th October, the War Office subsequently approved the issue of the plaque and scroll.

After the death of George, his wife Mabel continued living in Melton and never remarried. She passed away in 1948.

Lilian May went on to Marry Kenneth Daley in Melton and passed away in Macclesfield in 2000.

Montague Kitchener George joined the Northamptonshire Regiment during WW2. He married Joyce Weston in Northampton in 1943. He was taken Prisoner of War in 1943 in Germany held in Stalag IVG camp. He survived the war, returned to Northampton and passed away in 1981.

According to George’s service records, the cause of death was recorded as “Suicide self-inflicted wound during a state of temporary insanity due to A/S”.

What was the cause of this temporary insanity? Was it jealousy of his wife, was she having an affair? Was it a result of the injury sustained from being kicked by the horse? Was it the stress of military life, seeing the result of military action resulting in death and destruction in France?

I suppose that we will never know the truth behind this tragic incident in what the press reported as “Soldier goes mad – Suicide follows attempted murder at Melton” or “Another Domestic Tragedy at Melton”.

Soldiers described the effects of trauma as “shell-shock” because they believed them to be caused by exposure to artillery bombardments. As early as 1915, army hospitals became inundated with soldiers requiring treatment for “wounded minds”, tremors, blurred vision and fits, taking the military establishment entirely by surprise. An army psychiatrist, Charles Myers, subsequently published observations in the Lancet, coining the term shell-shock. Approximately 80,000 British soldiers were treated for shell-shock over the course of the war. Despite its prevalence, experiencing shell-shock was often attributed to moral failings and weaknesses, with some soldiers even being accused of cowardice.

But the concept of shell-shock had its limitations. Despite coining the term, Charles Myers noted that shell-shock implied that one had to be directly exposed to combat, even though many suffering from the condition had been exposed to non-combat related trauma (such as the threat of injury and death) like George Essex. Cognitive and behavioural symptoms of trauma, such as nightmares, hyper-vigilance and avoiding triggering situations, were also overlooked compared to physical symptoms.

Luckily for the sufferers of what we now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, it has been recognised that it is these cognitive and behavioural symptoms that define PTSD. The physical symptoms that defined shell-shock during WW1 were often consequences of the nonphysical symptoms.