Eighty years ago in the Summer of 1940 the fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force were in almost daily combat with the German Luftwaffe in the skies over our country and surrounding waters. Initially the Luftwaffe were set on trying to destroy our airfields in preparation for an invasion, but on the 7th September they changed their plans and swapped from destroying the airfields and the RAF to bombing our cities which subsequently became known as the Blitz.

The Battle has been described as the first major military campaign fought entirely by air forces. The British officially recognise the battle’s duration as being from 10th July until 31st October 1940.

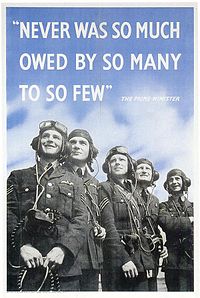

“Never In The Field of Human Conflict Was So Much Owed By So Many To So Few” was to become the famous words mentioned by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in his wartime speech that he delivered to the Nation on the 20th August 1940. By the time of Churchill’s speech, RAF fighter pilots had been in almost daily combat with the German Luftwaffe and those who flew combat missions during the battle have forever since been referred to as “The Few” and has been immortalised in posters just like the one below.

In this bog, I look at two very different war memorials that can be found in All Saints Church at Hoby near Melton Mowbray. Both memorials commemorate members of the Beresford family, one of which commemorates “One of the Few”.

War memorials can be found in all sorts of shapes, sizes and designs as mentioned in “Blog 19 – Protecting our War Memorials”. The memorials in All Saints Church take the form of a wooden Roll of Honour listing the names of 48 men from Hoby who served during World War One, a bronze tablet commemorating eleven men of the Parish who fell during the Great War, a stained-glass window commemorating the members of the extended Beresford family who made the ultimate sacrifice during World War One and a stone tablet commemorating another member of the Beresford family who was “One of the Few” and made the ultimate sacrifice during World War Two.

The memorials themselves are interesting, but they are more than just a name on a window or plaque, it is the stories behind those individuals names that make the memorials even more interesting providing links to not only military history, but also social history.

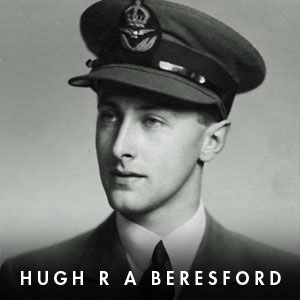

Flt Lt Hugh Richard Aden Beresford – One of The Few

On the Chancel wall opposite the Stained Glass window, is a plain stone tablet commemorating three members of the Beresford family, the Reverend Hans Aden Beresford, his mother Annie and the Reverends Son, Flight Lieutenant Hugh Richard Aden Beresford who was “One of The Few” and is the only Hoby casualty from World War Two.

Hugh Richard Aden Beresford was born 8th November 1915 and was the son of the Rector of Hoby & Rotherby, Hans Aden Beresford and his wife Dorothy Lydia Royston.

He was known by the family as ‘Tom’ and was educated at Rossell School in Fleetwood Lancashire. He was a keen sportsman and fine cricketer playing in the first XI team for four seasons and became team captain in his final year at the school.

Hugh joined the RAF on a short service commission in 1935 and after completing his training he was posted as a pilot to No 3 (Fighter) Squadron, arriving at Port Sudan as an Acting Pilot Officer on 23rd March 1936. Port Sudan is the Capital of Sudan and is located on the Red Sea coast. The aircraft operated by the Squadron was the Bristol Bulldog, until it was replaced by the Gloster Gladiator. Just over a year later, he was posted to the No 1 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit at Biggin Hill on the 12th April 1937.

On the 4th October 1937 he was appointed Personal Assistant to Air Vice-Marshal Ernest Gossage, Air Officer Commanding No 11 Group at RAF Uxbridge and on the 16th January 1938, Hugh was promoted to Flying Officer. Whilst at Uxbridge, in December 1939, Hugh married his wife Cherry Kyree ‘Pat’ Kemp, the daughter of a RAF Officer Walter Ernest Kemp.

On the 17th May 1940, No 257 (Burma) Squadron was reformed at RAF Hendon initially being equipped with Spitfires. Beresford joined the Squadron from HQ No 11 Group as Senior Flight Commander. The CO was Squadron Leader David Bayne who lost a leg in a flying accident whilst serving on No 3 (Fighter) Squadron, back in July 1935 when his Bristol Bulldog crash landed at RAF Duxford. This was the same Squadron that Hugh joined after leaving school.

During May and June, the Squadron was involved in training missions including bringing new pilots up to speed on Spitfires, Interception Exercises, formation flying, gunnery practice, night flying, high altitude (25000 feet) flying and dog fights.

On the 10th June, it was announced that the Squadron would be re-equipped with the Hurricane fighter, meaning more re-training for the pilots. The first eight Hurricanes arrived the next day with a further eight the day after. Training continued through June with the Hurricanes and on the 30th, the Squadron were informed they would be moving from RAF Hendon to their new base at RAF Northolt on July 4th.

Although the Battle of Britain hadn’t officially began (10th July), after settling in at Northolt on the 4th, the Squadron were put on Standby the following day at ¾ Hour before Dawn on the 5th. The Squadrons first scramble came on the 9th when Flt Lt Hall, PO Frizell and Sgt Forward were ordered into the air and Sgt Forward engaged a Do17 at 22000 feet.

Hugh had an aristocratic bearing which gave the men of his squadron much needed morale. He was affectionately known by his fellow pilots as “Blue-Blood Beresford” which was a reference to his aristocratic good looks and up-bringing.

Allegedly he was privately very nervous and vomited under the daily intense stress of the Battle of Britain. With exhaustion taking its toll on him, he was known for obsessively pacing up and down the dispersal hut continually asking “What’s the time?” and “I’m sure there will be a Blitz soon”. On 18th August, Hugh and Sgt Girdwood shared in destroying a He111 from III./KG 53 flown by Uffz Gustav Gropp which came down in the sea with all crew killed and a few days Hugh later claimed a Me110 on the 31st.

On 22nd July, the CO Squadron Leader Bayne was posted to HQ Fighter Command with Squadron Leader H Harkness taking over as Commanding Officer. Apparently the Squadron had poor leadership and was held together by two well respected Flight Commanders, Flt Lt Hugh Beresford and Fg Off Lance Mitchell.

Hugh Beresford and A Flight had patrolled Martlesham twice during the morning of the 7th followed by a 3rd patrol around Colchester at 11:15Hrs, landing at 12:20. At 14:15 the whole Squadron was called to 15 minutes readiness but were not ordered off.

Beresford in Hurricane P3049 along with 11 other Hurricanes of Yellow, Red, Blue and Green Sections of 257 Squadron left Martlesham Heath at 16:53Hrs to patrol Chelmsford area at 15,000 feet. They were vectored to the Rochester area under the Command of Squadron Leader Harkness when at 17:50Hrs they intercepted a formation of about 50 enemy bombers flying up the Thames estuary.

The large formation of enemy aircraft flying up the Thames were intent on sustaining the continuous bombing of London. An escort of Luftwaffe fighters above dived towards the squadron as they attacked.

The CO, Yellow 1 (Squadron Leader Harkness) passed the information about the enemy aircraft to “Kiwi 1” and the Squadron climbed up to their level, turning North. As they were coming from the Colchester area, they didn’t have the advantage of attacking out of the sun and must have been seen by the Me109s which were circling above the bombers at about 18-20,000 feet.

Yellow 1, followed by the Squadron, did a head on attack on the port section of three enemy aircraft. When Yellow 1 broke away to the right, Yellow 2 (PO Gundry) followed him without firing. Yellow 3 (Sgt Robinson) when following Yellow 2 in line astern, doing a steep turn to the right was thrown over on his back, losing control of his aircraft and dropped about 8,000 to 10,000 feet as a result of ant aircraft fire all around him.

Red 1 (Flt Lt Beresford) “A” Flight Commander followed Yellow Section into the attack and slightly to the right, is believed to have been unable to attack the bombing fleet head-on as his line of fire was obstructed by the leading Hurricanes. He climbed to about 500 feet in a clockwise circle above the bombers and turning to attack them from astern. At this point, Red 2 (Sgt Fraser) noticed at least four Me109 fighters with yellow noses swooping down on the section from astern.

Hugh Beresford tried to warn the other pilots of the danger over the radio by issuing a frantic warning “ALERT squadron – four snappers coming down now!” to the squadron about the attacking fighters, stating that he could not attack as another Hurricane was in his line of fire. (ALERT was the radio call sign for 257 Squadron). Then there was silence. In his final few moments of life he had used his last breath to save others.

None of the squadron saw what had happened to him, but a River Board worker inspecting the water ditches which criss-crossed the flat Isle of Sheppey, was watching the dog-fight developing above in a crescendo of engine noise and rattling of machine guns. He saw a lone Hurricane break away and dive vertically into the soft estuary ground alongside a ditch at Elmley Spitend Point, Sheppey.

There was no fire or explosion, just a small crater with a black stain and slashes either side where the wings had cut through the grass. No time could be spent during the weeks of the Battle of Britain to mount salvage operations and as the aircraft was deeply buried it was eventually forgotten.

From the combat action in the 7th, three pilots failed to return, Hugh Beresford, the other Flight Commander Lance Mitchell and Sgt Hulbert. Later, the Squadron received news that Hulbert was OK and had crash landed near Sittingbourne. None of the other pilots could provide any info on what had happened to the two Flight Commanders and enquiries were made with other RAF airfields, Police HQs and Royal Observer Corps observation posts but nobody saw what happened.

Hugh’s wife, Pat, rang the Squadron in tears on the evening when he failed to return. The Squadron Adjutant spoke to her and telling her that he might have been picked up by boats in the sea and not to give up hope. It was as if she new his fate as she asked if she could pick up his clothes.

Hugh Beresford was classified as missing in action and an Air Ministry telegram was sent to Pat telling here that he had failed to return from an operational flight and they would contact her again as soon as possible when they received further news. No news came forward, and one year after he went missing, he was officially presumed dead.

Shortly after his Hurricane had plunged into the marshy ground, RAF personnel from nearby RAF Eastchurch came to the crash site and as little could be done, they reported it to No 49 Maintenance Unit who covered the South East of England

Ten days after Hugh’s disappearance, Air Vice-Marshal Ernest Gossage wrote to Reverend Hans Beresford, explaining that Hugh had once been his personal assistant and that he had become very fond of him. His letter also said that he wanted to make sure that no possibility of him being alive before he wrote with his sincere and heartfelt sympathy.

For decades no one knew the exact spot where he laid buried. 39 years later, in August 1979, there was renewed interest by aviation enthusiasts in locating and excavating the wrecks of wartime planes. Hugh Beresford’s Hurricane was discovered and on 29th September 1979 the entire wreckage was recovered with Hugh’s body being found still in his aircraft. Hugh Beresford and his tattered identity card were recovered.

Forty years to the day he was shot down, on the 7th September 1980, BBC2 Television documentary series Inside Story screened a programme “Missing” all about Hugh Beresford and the remarkable story of him being reported as missing in 1940 and the discovery of his Hurricane fighter with his remains still in the cockpit.

He was laid to rest with full military honours in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, with the Band of the RAF and the Queen’s Colour Squadron providing the honours. Hugh’s sister, Pamela who lived in Hoby village attended his funeral along with a few other residents from the village.

For more details about his burial at Brookwood Military Cemetery, see his CWGC Casualty Record.

Additionally, the CWGC E-Files archives holds a series of black and white images showing CWGC staff erecting his headstone, levelling it off, applying soil to the border, cleaning it and finally with the plants in place around it. To view the images, visit the CWGC archive site and enter Beresford in the search box.

In 2022 I was on a visit to Brookwood Milirat Cemetery so whilst there, I took the opportunity of visiting Hugh and paying my regards.

The personal insciption at the bottom of his head stone was chosen by his family and comes from a poem titled “No One So Much As You” by Edwrad Thomas

NO ONE SO MUCH AS YOU LOVES THIS MY CLAY, OR WOULD LAMENT AS YOU ITS DYING DAY

No One So Much As You by Edward Thomas

No one so much as you

Loves this my clay,

Or would lament as you

Its dying day.

You know me through and through

Though I have not told,

And though with what you know

You are not bold.

None ever was so fair

As I thought you:

Not a word can I bear

Spoken against you.

All that I ever did

For you seemed coarse

Compared with what I hid

Nor put in force.

My eyes scarce dare meet you

Lest they should prove

I but respond to you

And do not love.

We look and understand,

We cannot speak

Except in trifles and

Words the most weak.

For I at most accept

Your love, regretting

That is all: I have kept

Only a fretting

That I could not return

All that you gave

And could not ever burn

With the love you have,

Till sometimes it did seem

Better it were

Never to see you more

Than linger here

With only gratitude

Instead of love –

A pine in solitude

Cradling a dove.