As the Country and the rest of Europe were rejoicing in the end of fighting and their countries being liberated from Nazi Germany, tragedy struck a Melton family as they received news that their son had been killed in Holland, two days after VE Day.

The Melton Times published an article titled “MELTON SINGER KILLED“ about Private Lawrie Hart. ‘Lawrie’ is the Great Uncle of my wife.

“Mr. and Mrs. T. K. Hart, of 14, Eastfield Avenue, Melton, this week received news that their youngest son, Pte Lawrie Hart, had been killed in Holland.

The funeral took place at Hilversum with full military honours.

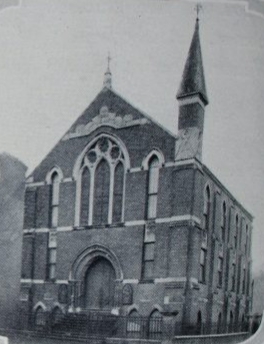

Pte Hart was a popular Melton singer. He had been a member of the Melton Operatic Society for about six years, and used to sing in the choir of Sherrard Street Methodist Church.

Aged 24, Pte Hart had been in the forces three years. He went to France about 10 months ago.

After leaving school, he served his apprenticeship with Messrs E Clarke and Sons, Snow Hill, Melton, until he was called up.”

Lawrence Copley Hart was born 6th March 1921 and was the youngest son of Tom Kemp Hart and his wife Alice Hart (Nee Copley). His 3 elder brothers were Albert Ernest (b.1905), William (Bill) (b.1908) and Cecil Harry (b.1910).

As the Melton Times had reported, he served his apprenticeship with Messrs E Clarke and Sons and his trade was a bricklayer, the same as his elder brother Cecil.

On the 19th Feb 1942, Lawrie was enlisted into the Leicestershire Regiment and started his military career at No. 22 Infantry Training Centre at Warwick, used for training soldiers from both the Leicestershire Regiment and the Royal Warwick Regiment. according to his enlistment papers, his height was recorded as 6 feet and half an inch.

He stayed at the Warwick ITC until he completed his basic training when he was transferred to join the 1st Battalion the Leicestershire Regiment on 30th July 1942 at the historic and renowned Gresham School at Holt in Norfolk.

In 1942, Lawrie qualified as a Gunner by passing his Mortar training.

In early 1943, The Bn moved from Holt to Purley in Surrey taking up defence duties in London and the south of England. In April 1944 the battalion was deployed between Goodwood and Chichester organised into flying columns reinforcing RAF regiments defending sixteen airfields in the area including the famous Tangmere airfield. An additional task was to guard the cordoned area for the Mulberry Harbour construction site.

After ‘D’ Day, 6th June the battalion moved back to Purley on the 14th where a V1 rocket (buzz bomb) took out 21 vehicles including Bren-gun carriers enabled for amphibious landing. The next morning drivers reported to collect replacements vehicles.

At 21:00Hrs on Saturday 1st July 1944, the Brigade Major arrived with orders for the Bn to move to France on the next day to replace the 6th Duke of Wellingtons Regiment who had received heavy casualties and had been withdrawn to the UK following heavy losses at the battles of Le Parc de Boislande and Juvigny on the Western outskirts of Fontenay-le-Pesnel.

The following day, at 14:00Hrs, the 1st Bn Leicestershire Regiment left Purley on the first part of their journey into France, Belgium, Holland and into Germany. On leaving Purley, the troops shouted to their well-wishers “Monty has decided he cannot do without us!”.

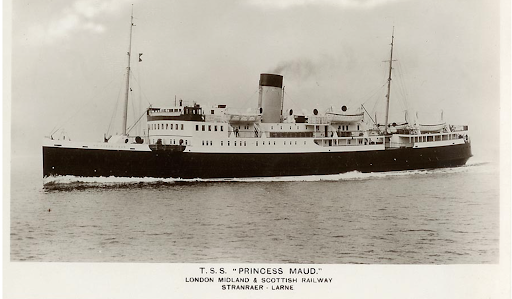

From Southampton, they sailed on the Princess Maud a veteran of the Dunkirk evacuation. The ship was shelled in the engine room taking fatalities on 30 May 1940. On 4 June 1940 following repairs she was able to return to the evacuation rescuing 1270 in a single trip being the penultimate ship away from Dunkirk.

She subsequently assisted the evacuation of British and French troops from Veules-les-Roses around 12 June 1940 at the time of the surrender of the 51st Highland Division at Saint-Valery-en-Caux, a few miles to the west, transporting 600 British and French troops of the 2,280 rescued.

She then reverted to serving the Stranraer-Larne route on behalf of the Admiralty until in 1943 when she received modifications for D-Day landing operations to turn her into an infantry assault trip capable of launching six Landing Craft Assault (LCA) boats via hand hoists.

For the D-Day landings she was attached to the US Task Force Operation Neptune Force O at Omaha beach. She is reputed to have carried 1,360,378 troops in her war service.

The 1st Bn Leicestershire Regiment was part of the 148th Brigade, 49th Division, known as the Polar Bears. Alongside the 1st Leicesters, the 49th was also made up of units including the Durhams, the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, the Lincolns, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Tyneside Scottish, the Kent Yeomanry, the Loyal Suffolk Hussars, 89th LAA (the Buffs) and in August 44 were joined by the South Wales Borderers, Gloucesters and Essex Regiments.

On arrival in France, the 1st Bn landed on the beaches at Arromanches Mulberry Harbour on the 3rd, just a few miles from Courseulles-sue-Mer and concentrated at Carcagny on the 4th July. Under the command of Lt Col Novis, they marched to Cristot and joined the 11th Royal Scots Fusiliers and the 7th Duke of Wellingtons Regiment of the 147th Brigade on the 6th July. They then had 5 days when most of the officers and NCOs had a short attachment to the units in the line. On the 13th, the Bn went fwd into the line near Fontenay having relieved the 4th Royal Welsh Fusiliers of the 53rd Welsh Division.

The Leicesters spent from 24th July to 10th August in the line at Le Poirer with a 2,000 yard front where they actively patrolled frequently under enemy shelling and mortaring.

On the 22nd August, The Leicesters played a big part in the battle to take Ouilly-le-Vicompte with their pioneer platoon setting up ropes for them to cross the 20 feet wide river Toques. Their first battle was a success despite a fierce counter attack in the afternoon. The rifle companies nearly ran out of PIAT and small arms ammunition and approximately half of their 20 stretcher bearers had been hit. Despite heavy shelling which had cost the lives of 1 officer and 11 men plus wounding a further 35, the Leicesters had defended their bridgehead.

During the period 10-12 September, the Leicesters were involved in Operation Astonia, The assault on Le Havre. At 23:00Hrs on the 10th, the 1st Leicesters attacked, the tracks and roads were still found to be heavily mined and progress was slow. By noon on the 11th, the Bn finally captured its objective East of the Forêt de Montegon and a vital bridge leading into the port.

After a weeks rest, the Bn was re-organised near Pont Audemer and was now commanded by Lt Col F W Sandars DSO. The key road was still heavily mined with blown up vehicles blocking it.

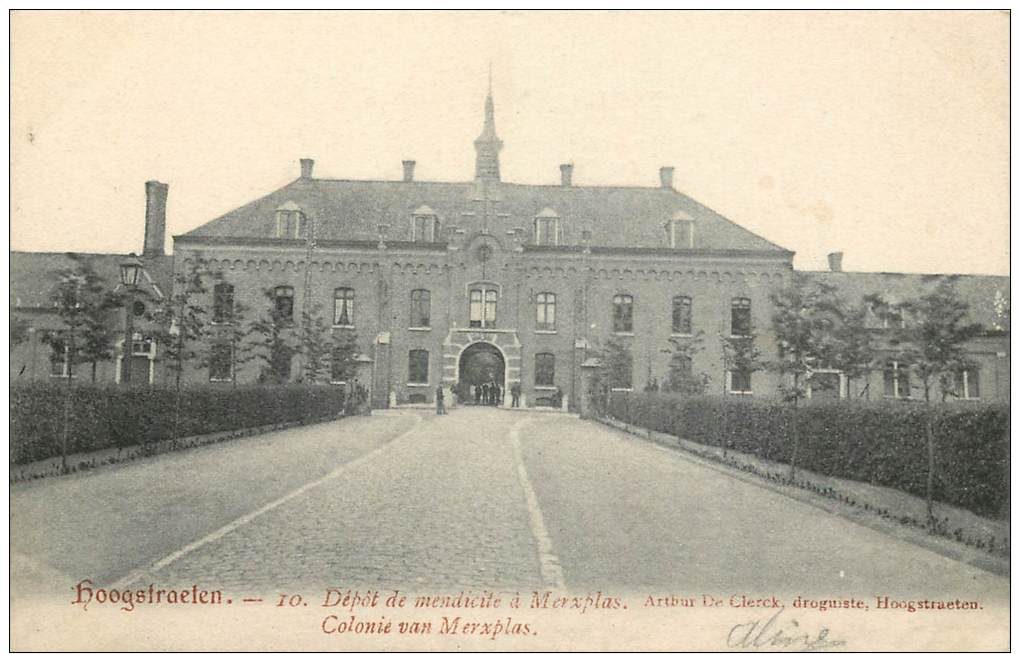

The 1st Leicesters were again in battle on the 29th in what was known as the Battle for Mendicité, a formidable barrack block made up of a combined prison, workhouse and lunatic asylum. Situated in 100 acres of farmland, intersected by deep ditches, the main enemy position had been reinforced by a second battalion and was surrounded on 3 sides by a moat, 20 feet wide and 3 feet deep.

Along with the Lincolns, the Leicesters cleared the north bank of the canal, they then proceeded to attack the Mendicité from the West whilst the 7th Dukes and Glosters attacked from the South. The Leicesters battled away throughout the day capturing the key road bridge. By late evening, Mendicité had been captured at a cost with the Leicesters losing 70 men either killed wounded or captured.

There were many feats of gallantry and some were awards were given out, For the Leicesters, Lt V F W Bridgwood won an immediate MC, as did Lt F A Gaunt. D Companys CO Peter Upcher who led the assault won a DSO. Pte C H Woods, Cpl W A Saunders, Sgt W Irwin and Sgt T Johnson all received the MM. Following the capture of Mendicité, the Bn moved from Belgium into Southern Holland.

On the 28th October, the Leicesters were once again in battle, this time as part of the Battle for Roosendaal. The main attack was from the 147th Brigade from the south, the 1st Leicesters on the left and the 7th Dukes on the right with eh 4th KOYLI and 11th Royal Scots Fusiliers to pass through and capture the town.

On their way north towards Roosendaal, the Leicesters were involved in a battle at Brembosch. Under heavy fire the Bn proceeded to Roosendal which they made by nightfall having suffered 17 casualties.

The Leicesters were involved in the Battle of Zetten took place on the 18th/19th January 1945 and during he 2 days of fighting they suffered 60 casualties whilst they accounted for 150 Germans killed wounded or captured.

From Zetton, the Leicesters made their way through Holland passing through Nijmegen and travelled down the river Neder Rijn to Arnhem using the 36th LCAs of the 552nd Flotilla. On reaching Arnhem they made their way to the top of Westervoorsedijt near the harbour and dug in near the Elisabeth Hospital.

On the evening of the 4th May, came the news that all German troops in NW Germany, Denmark and Western Holland had unconditionaly surrendered, to take effect from 08:00Hrs on the 5th. On the 6th, Maj Gen Rawlins met the Commander of the German 88th Corps to arrange the occupation of NW Holland and the disarming and concentration of the enemy.

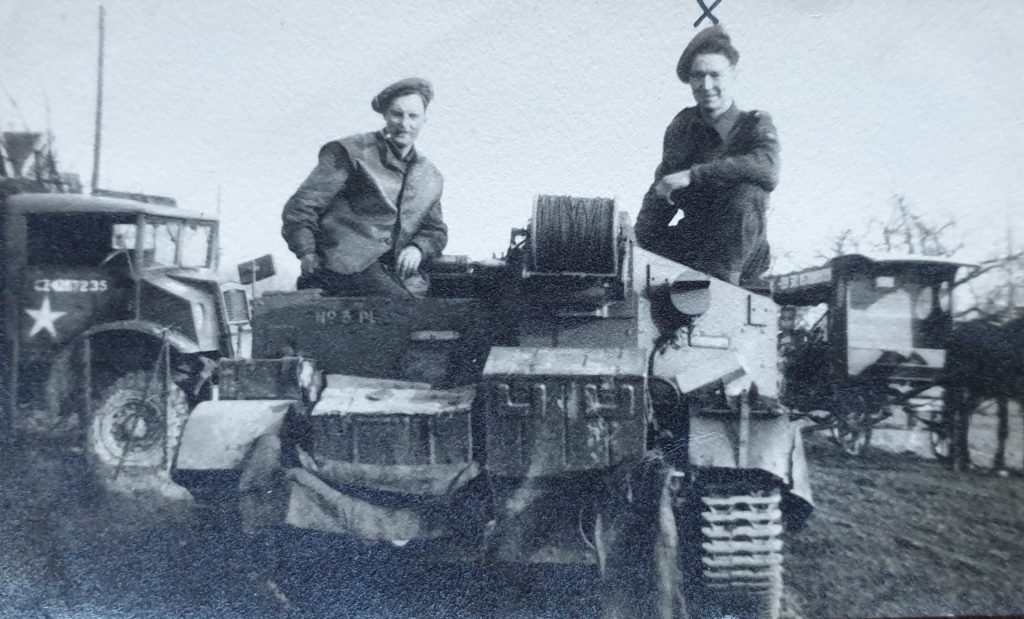

The plan was for the 49th Division to disarm the three divisions holding the Grebbe Line based on Holversum and Utrecht. The 49th ‘customers’ were the 6th German Parachute Division who they had previously engaged in battle at Nijmegen bridge. The 1st Bn moved to Hilversum to disarm the Wermacht.

On Saturday 5th May 1945, the 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment was located in the area around Lunteren when they were visited by their popular (former) Commander, Lieutenant Colonel PAB Wrixon. He was warmly welcomed by the soldiers who had served under him in Hinckley, Holt and Purley. On Monday 7th May they left Lunteren to arrive in Hilversum after a stop en route on 9th May.

On arrival at Hilversum, they saw large numbers of German troops against whom they faced up earlier in their journey through the Netherlands. Their Germans transport column consisted mainly of horse-drawn wagons, rather old-fashioned compared to their own military vehicles.

During their arrival in Hilversum, they were literally surrounded by a delirious crowd. Their hospitality towards the Leicesters soon became apparent and a short time later the Bn was well quartered.

The Support Company was housed in a school and soon the schoolyard was filled with the Leicesters military vehicles. The Germans had robbed the population of almost everything and the people were starving. The authorities realized this well and immediately after the announcement of the armistice, trucks loaded with food drove to all corners of the Netherlands.

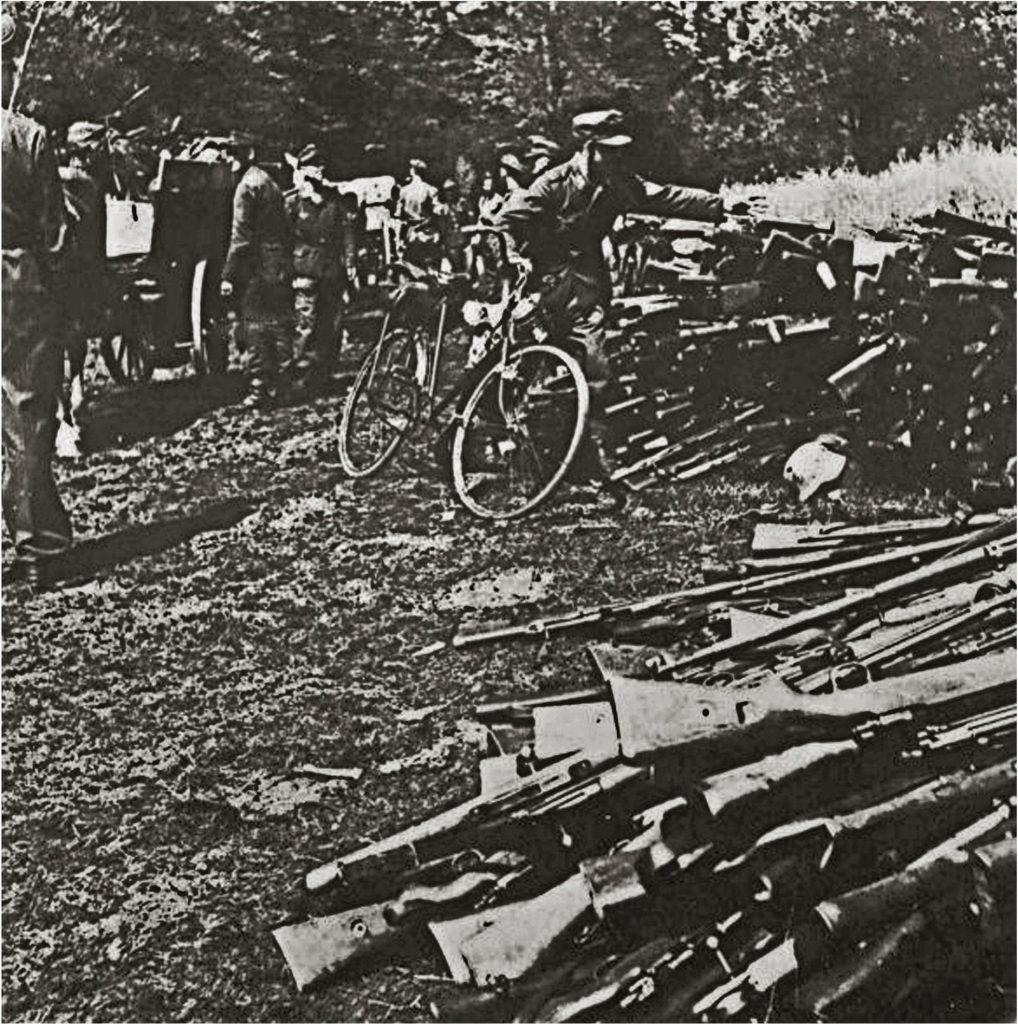

The enemy was gathered and taken to designated areas where they had to hand over their weapons and were searched. On the 10th May, the Leicesters started their mission: to disarm the German troops in their area. The German troops belonged to the ‘Hermann Goering Para Division, with whom they had previously fought.

The disarmament area was located in a site a few kilometers outside Hilversum. After a successful start, the Battalion was soon afterwards faced with a tragedy. When the Germans arrived on the ground, they first delivered their rifles and small arms under the supervision of the Support Company and then walked on to deliver machine guns and mines. Finally, they had to go across the site to hand in their connectors and other equipment.

The order for the platoon was to let the Germans do the work. A short time later, a closed horse carriage with a door at the back entered the site. The driver said he had bread rations for the German troops. He told Sgt Dixie Dean to open the door at the back and he saw that the cart was indeed half filled with bread. The driver wanted to close the door quickly again, and Dixie became suspicious and let him unload all the bread. No wonder he was so strange: under the bread a square wooden box, about 45 by 45 cm, full of pistols, mainly Lugers was found! The box of Lugers was confiscated and he was allowed to put the bread back in the cart and continue on his journey.

A few minutes later, a lorry with trailer came onto the site and the driver was instructed to drive to the unloading point. The truck was mainly loaded with mines and grenades. A company of soldiers had entered the site on foot when there was a huge explosion. Sgt Dixie Dean was blown upside down, together with some Germans who were stacking their guns. Fortunately, he got up unharmed and ran to the truck, blown over by the explosion, along with the trailer. The explosion had created a crater about 1.80 meters deep and 3.50 meters in diameter.

The dazed survivors were put to work trying to free the injured from the debris. Unfortunately, there were only a few. After a roll call was taken, it became clear that eleven men from the Mortar platoon and two from the Antitank platoon were missing and most likely killed. A number of Germans also died in the explosion.

When the roll call was taken after the explosion, Sgt Dixons attention was drawn to a Dutch citizen who was waving in the middle of the site next to us. A soldier was sent to ask what he wanted. When he returned, he said that a body had been found. It was undoubtedly the body of a British soldier. It turned out to be the body of soldier H. Hall, who had been added to the Mortar platoon since the Normandy landing. The force of the explosion can be measured by the fact that his body was more than 80 to 90 meters from the crater.

The only ones of the Mortar platoon to survive, although severely wounded, were soldier Jack Knight along with Sergeant Gosling. As far as Knight could tell, it was seen that a German who was unloading the truck threw a Teller mine (used to destroy the tracks of tanks) on a pile of mines previously unloaded . This or one of the stacked mines must have exploded. If the ignition hadn’t been in the mine, it would have been nearly impossible for it to explode.

This was confirmed by a sergeant ammunition expert, who arrived at the scene of disaster shortly after the tragedy. Since the German who threw the mine had also died, it was impossible to give a more accurate description of what happened. Whether the explosive was deliberately thrown to make casualties among the English soldiers and whether the ignition was set will never be revealed.

This tragic event was particularly hard on everyone, especially the men of the Mortar platoon who had lost so many comrades. After the landing on the beaches of Normandy, they had all moved up without further losses and now, a few days after everything was over, lost their lives in this very tragic way.

On 12th May, the killed soldiers were buried in the cemetery in Hilversum, where they still have their final resting place to this day. The Bn experienced genuine compassion as the trucks with the coffins aboard passed lines of the Dutchmen gathered along the route who expressed their feelings with flowers.

On Sunday, May 13, the day after the funeral, the Adjutant, Captain John Stevenson, summoned the Commander of the Anti-Tank Platoon and Sgt Dixon. He said that a report had been received from Headquarters regarding a German unit that also reported several casualties as a result of the explosion. They had taken away a body they suspected may have been one of our people. They were instructed to visit this German unit and to verify all this.

On arrival they were taken to a place where the body had been placed, but identification proved impossible. Although a British boot, trousers and spats, were seen, these were not marked with an army number. We returned to our unit and reported to the Adjutant. Later we heard that the body was buried under the supervision of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in the cemetery in Hilversum.

The members of the 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment killed in the explosion were: Mortar Platoon: Private TVH Atkin, Corporal J. Fisher, Private H. Hall, Private LC Hart, Lance Sergeant OW Hartshorn, Private VG Langley, Private EC Obeney, Lance Corporal S. Onion, Private DE Wain, Lance Corporal RJ Walley, Corporal LGE Whitehall and of the Antitank Platoon: Private RHC Hyde and Private R. Wood.

German soldiers also died in the accident. The names of two of them are: Obergefreiter Franz Rauecker and Gefreiter Max Salzinger.

After the War, the Hart family visited Lawries grave at Hilversum.

Grave of Pte Lawrence Copley Hart taken during our visit to his grave on 28th May 2015

For more information about his grave, visit his CWGC casualty record.

We Will Remember Them.