The Victoria Cross (VC) is one of the highest awards a British soldier can receive. It requires an act of extreme bravery in the presence of the enemy, and has achieved almost mythical status, with recipients often revered as heroes.

The VC is Britain’s joint-highest award for gallantry. It was only equalled in status in 1940, when the George Cross (GC) was instituted for acts of conspicuous bravery not in the enemy’s presence.

The prototype Victoria Cross was made by the London jewellers Hancocks & Co, who still make VCs for the British Army today. According to legend, the prototype, along with the first 111 crosses awarded, were cast from the bronze of guns captured from the Russians in the Crimea. There is, however, a possibility that the bronze cannon used was in fact Chinese, having been captured during the First China War (1839-42) and then stored at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich.

When you talk about VC Heroes and Melton Mowbray, the majority of people recall Richard ‘Dick’ Burton. It is true to say that Dick Burton is the only Meltonian to be awarded a Victoria Cross, but as the word ‘heroes’ suggests there are actually more than one VC recipients commemorated in the town, but who are they and why were they awarded their VCs?

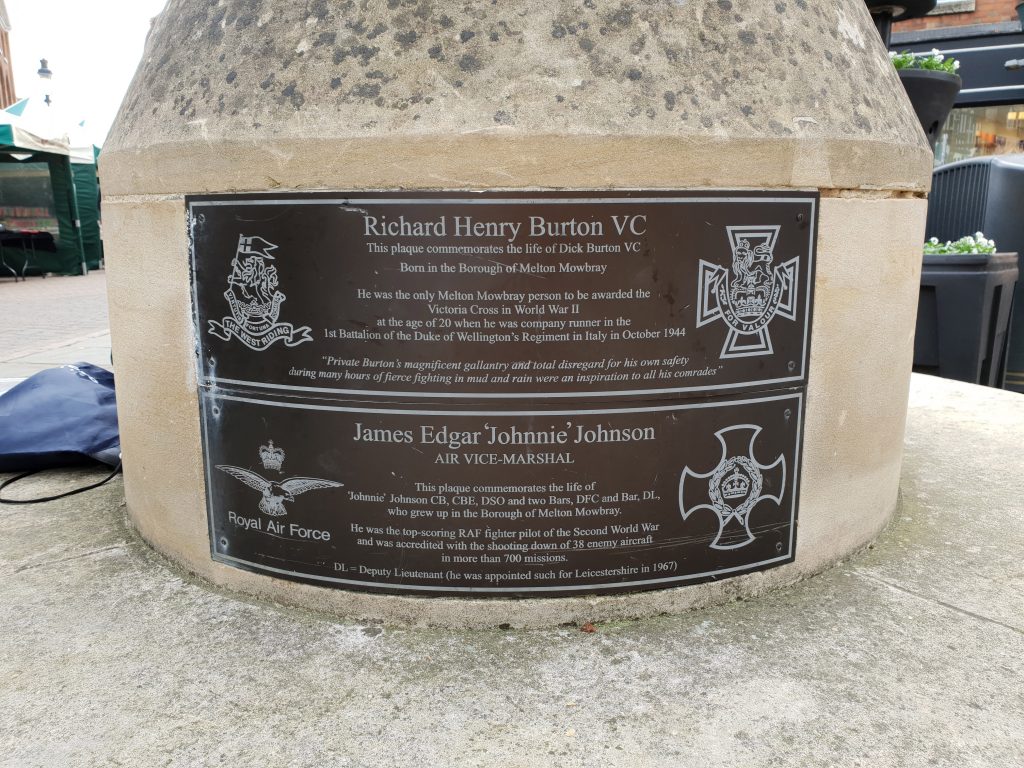

If you take a close look at the Corn Cross in Melton Mowbray at the junction of High Street and Nottingham Street, you will see two small plaques, one commemorating Dick Burton and the other commemorating another Meltonian who was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Distinguished Flying Cross during World War Two; Air Vice Marshal James Edgar ‘Johnnie’ Johnson, CB, CBE, DSO and Two Bars, DFC and One Bar, DL.

These same two individuals are also commemorated in the Royal British Legion Field of Remembrance at the entrance of the Egerton Lodge Memorial Gardens with the placement of two small black crosses with plaques inscribed with their names. The Gardens were bought in 1929 by Melton Mowbray Town Estate and developed into a permanent memorial of those who fought in both World Wars.

Private Richard Burton

Richard Henry Burton, known as ‘Dick’, was born in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire on 29th January 1923, the son of George Henry Burton and his wife, Muriel. He grew up in the market town, living on Egerton Road, and went to school in the town until he was 14. One of the schools he attended was the Brownlow School on Limes Avenue where you will find a wooden memorial plaque commemorating him.

After leaving school, Dick became a bricklayer and followed his father into the building trade until the age of 19. Still a teenager, he enlisted into the Northamptonshire Regiment in 1942, before he joined the Duke of Wellington’s (Dukes) to go to French North Africa, where he fought in the Tunisian campaign.

With his regiment, Private Burton went onto capture the Island of Pantellaria in the Mediterranean Sea between Tunisia and Sicily in 1943. Afterwards he took part in the famous Anzio beach landings in January 1944, fought his way up through Italy. Anzio cost the Dukes 11 officers and 250 other ranks wiped out. Burton’s CO was wounded.

The northward slog was a costly affair for the Dukes. The atrocious weather conditions reduced the battalion to mule transport, laden mules becoming ‘bellied’ in the mud under the weight of ammunition or stores. Thus the Dukes confronted Monte Ceco, a crucial 2,000ft feature, on the Gothic Line in October 1944, a six-day battle ensued in rain. The initial attack from the south failed, one of the causes of the failure being the mud in places was knee-deep. On the evening of the 8th October, a silent second attack from the west was launched in a downpour whilst under heavy German mortar fire.

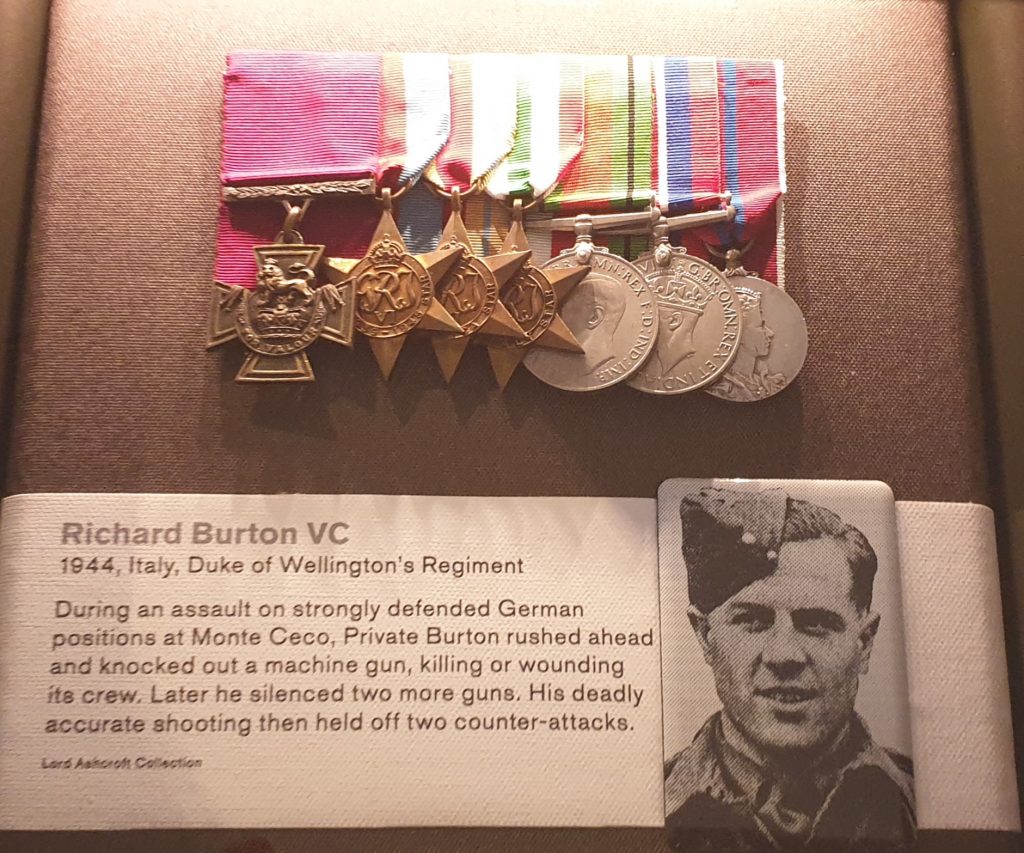

In the final stages of the assault on Monte Ceco, Captain A. Burns took Burton, the runner, with his platoon through to assault the crest which was held by five Spandau machine-gun teams. Despite withering German fire, Burton managed to kill the first team with his tommy-gun; and similarly the next until his ammunition ran out. He then picked up a Bren light machine gun and firing from the hip, neutralised two further German machine-gun teams, allowing his company to consolidate on the forward slope of Monte Ceco.

The Germans counter-attacked fiercely. Burton, with his companions lying dead or wounded around him, beat off that attack with accurate Bren fire. A second German counter-attack was mounted on Burton’s flank and, firing in enfilade, he again broke up the impetus of this attack, saving his company’s position.

In a letter to his parents in Melton Mowbray Private Burton wrote: “I think I am in for some sort of medal. The sergeant with me received the DCM, and three Military Medal’s were distributed at the same time. They told me mine ought to be a VC, but I don’t know about that. Anyway, I have paid the Boche back for my wounds. I must have gone bomb-happy or mad.”

The announcement of his award of the Victoria Cross in the Lancashire Evening Post stated that it was the 124th VC of the war and the 85th to go to the Army. His award was published in The London Gazette 4th January 1945 and he received his award from King George VI at Buckingham Palace the same month.

Burton’s VC citation ends with: ‘Private Burton’s magnificent gallantry and total disregard for his own safety during many hours of fierce fighting in mud and continuous rain were an inspiration to all his comrades.’

Dick Burton was barely a man at the time, a quiet boy who knew his duty. His medal embarrassed him, not only then but in the years that followed. To the end he remained modest, disliking fuss. He was a man tall and well set up, with nothing abrasive in him. There are essentially two sorts of VC courage: the calculating and cold, calling on intellect (such as the pilots showed); and the fiercely physical, which is ‘hands-on’ and calling on reserves of will. Dick Burton had that will, that conviction, from boyhood.

When station in Scotland, Dick met a young Scottish lady called Dorothy Robertson Leggat in the foyer of the Pavilion Cinema at Forfar. During his time in Scotland, their relationship bloomed rapidly, and he used to go and visit her family in Kirriemuir regularly.

After the war, Dick and Dorothy were married in 1945 and they went to live in Kirriemuir, where they brought up three boys and a girl. The Leicestershire lad became a convert Scot, even to the accent. After the war, Richard had returned to the building trade, and stayed in the business until retirement. He passed away on 11th July 1993 in Kirriemuir, aged 70, and was laid to rest in Kirriemuir Cemetery in the same grave as his son.

In 1998, at an auction at Spink’s, London, Burton’s medals including his VC were purchased by Michael Ashcroft and are now part of the Ashcroft Gallery, Imperial War Museum.

Victoria Cross Flower Beds

As you enter the Egerton Lodge Memorial Gardens, you will pass the Royal British Legion Field of Remembrance on your right hand side with the two black crosses for Dick Burton and Johnnie Johnson as mentioned previously. Follow the path around and you will notice two large flower beds. There is one bed either side of the central path leading up to Egerton Lodge and the War Memorial, both set out in the shape of a Victoria Cross.

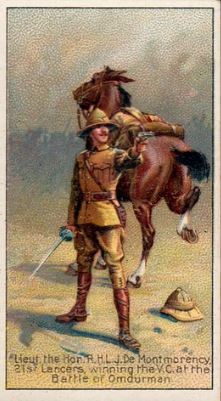

The information board (above) at the entrance of the Egerton Lodge Memorial Gardens states that the flower beds were designed to honour two more recipients of the Victoria Cross who have connections to Melton Mowbray. Captain Paul Kenna and Lieutenant the Hon. Raymond Harvey Lodge Joseph De Montmorency who were both members of the 21st Lancers and visited Melton as part of the hunting society.

The two officers are known to have stayed in Melton Mowbray during the late 1890’s and are reputed to have been guests staying at the Bell Hotel in 1899. Their friend, Lieutenant the Hon. Richard Frederick Molyneux of the Royal Horse Guards was also present in Melton at the same time, staying at the Blakeney Institute.

The three Officers were veterans of the Battle of Omdurman that took place in 1898 where all three were involved in the famous Lancer Charge during the battle. According to the book “Melton Mowbray Queen of the Shires” by Jack Brownlow, they all carried marks of the fight.

Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman took place on 2nd September 1898 at a place called Kerreri, 6.8 miles north of Omdurman. Omdurman today is a suburb of Khartoum in central Sudan and sometimes the battle is referred to as the Battle of Khartoum.

British General Sir Herbert Kitchener commanded a mixed force of 8,000 British regular soldiers plus a further 17,000 troops from Sudan and Egypt. Kitchener’s enemy, led by Abdullah al-Taashi, consisted of some 50,000 soldiers including 3,000 cavalry. They called themselves the Ansar, but were known to the British as the Dervishes.

Directly opposite the British force was a force of 8,000 men spread out in a shallow arc about a mile in length along a low ridge leading to the plain. The battle began at around 6:00 a.m. in the early morning of the 2nd September when Osman Azrak and his 8,000 strong mixed force of riflemen and spearmen advanced straight at the British.

The British artillery opened fire inflicting sever casualties on the attacking force resulting in the frontal attack ending quickly after the attackers had received about 4,000 casualties.

General Kitchener was keen on occupying Omdurman before the remaining Mahdist forces withdrew there so he advanced his army on the city, arranging them in separate columns for the attack. The 21st Lancers from the British Cavalry were sent ahead to clear the plain to Omdurman.

The 21st Lancers were made up of 400 cavalrymen and thought they were attacking a few hundred Dervishes, but little did they know that there were 2,500 infantry hidden in a depression. Consequently, the Lancers fought a harder battle than they expected losing twenty-one men killed and fifty wounded. After a fierce clash, the Dervishes were driven back.

One of the participants of this battle was a young Lieutenant by the name of Winston Churchill who was attached to the regiment from the 4th Hussars, commanded a troop in the charge. It was during this same battle that four Victoria Crosses were awarded, three of which went to the 21st Lancers for helping rescue wounded comrades. Churchill’s book “The River War: an Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan” provides a good account of the Battle of Omdurman.

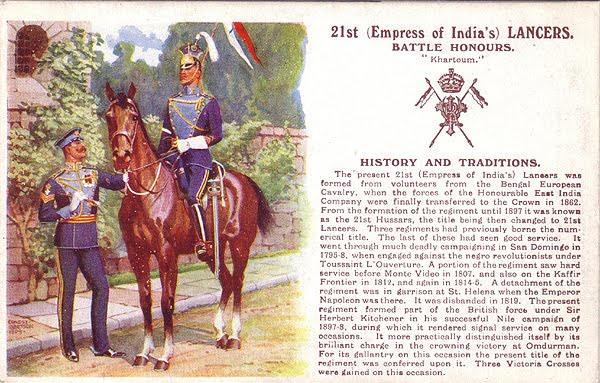

As a result of the charge at Omdurman, the 21st Lancers was awarded the title ‘Empress of India’s’ by Queen Victoria, becoming the only regiment entitled to wear her Royal Cypher, and was allowed to return its french-grey facings, which had previously been replaced by scarlet. To this day men of The Queen’s Royal Lancers still wear a form of Queen Victoria’s Royal Cypher on their uniform.

Two of the Lancers VC awards that day went to Captain Paul Kenna and Lieutenant the Hon. Raymond Harvey Lodge Joseph De Montmorency who as mentioned previously are commemorated in the Egerton Park War Memorial Gardens with the VC shaped flower beds designed in their honour.

Captain Paul Aloysius Kenna

Kenna was 36 years old and serving as a Captain with the 21st Lancers (Empress of India’s) during the Sudan Campaign when he undertook the deed for what he was to be awarded the Victoria Cross.

On the 2nd September 1898, during the Battle of Omdurman, a Major of the 21st Lancers was in danger as his horse had been shot during the charge. Captain Kenna took the Major up on his own horse and back to a place of safety. After the charge, Kenna returned to help Lieutenant De Montmorency who was trying to recover the body of a fellow officer who had been killed.

Captain Paul Kenna received his Victoria Medal from Queen Victoria at Osborne House, Isle of Wight on 6th January 1899.

Following the Sudan campaign, Kenna later served in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and was promoted to Brevet-Major on 29th November 1900. For his service in the war, he was appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) on 26th June 1902.

Following the end of the South Africa War, Kenna returned to England in July 1902. He was promoted to Major on the 7th September 1902 and appointed to command a Mounted flying column in Somaliland.

He retired from the regular Army in September 1910 with the rank of Colonel. However, in April 1912 he was appointed to command the Notts and Derby (Yeomanry) Mounted Brigade.

In 1912, he competed for Great Britain in the Summer Olympics as a horse rider in the individual eventing (military) competition. He did not finish the individual event nor did the British team finish in the team event. He also competed in the individual jumping event where he finished 27th.

At the outbreak of World War One he was appointed Brigadier-General. In the spring of 1915, he took the 3rd Mounted Brigade to Egypt and later to Gallipoli. On 30th August 1915, he was hit by a Turkish sniper’s bullet whilst inspecting the frontline trenches and died of his wounds.

He is buried in the Lala Baba (CWGC) Cemetery, Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, Turkey. For more details, see his CWGC Casualty Record.

He left a widow, Angela Mary (his second wife), and two daughters. His medals are held by the Queen’s Royal Lancers Museum, Thoresby Park, Nottinghamshire.

Lieutenant the Hon. Raymond Harvey Lodge Joseph De Montmorency

De Montmorency was born on 5th February 1897 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada and was the eldest son of Major General Reymond de Montmorency, 3rd Viscount Frankfort de Montmorency and his wife Rachel Mary Lumley Godolphin Michel.

He joined the Army on 14th September 1887 when he took out a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Lincolnshire Regiment. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 6th November 1889 and transferred to the 21st Lancers (Empress of India’s).

After the charge of the 21st Lancers during the Battle of Omdurman on the 2nd September 1898, Lieutenant de Montmorency returned to help an officer, 2nd Lt R G Grenfell, who was lying surrounded by the Dervishes. Montmorency drove the Dervishes away only to find the 2nd Lt Grenfell was dead. He put the body on his horse which then broke away. Captain Kenna and Corporal Swarbrick came to his assistance, thus allowing Montmorency to rejoin his cavalry regiment.

After Sudan, like his colleague Paul Kenna, Montmorency served in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). In October 1898 he had been despatched to South Africa on special service. He was promoted to Captain on the 2nd August 1899 following which he raised and commanded a special body of Scouts known as Montmorency’s Scouts.

The Victorian illustrated weekly publication Black and White Budget provided its readers with coverage of the 2nd Boer War and in their issue on 13th January 1900 commented “Captain de Montmorency, who is the commander of some mounted scouts with General Gatacre’s force, is showing the great value of horsemen in fighting the Boers. As soon as the enemy find themselves out-flanked by Montmorency’s men, they make a very hurried movement to the rear, and the fight is over so far as they are concerned. Captain Montmorency is the hero of the 21st Lancers, and won the Victoria Cross at Omdurman in 1898 by returning, after the charge, for the dead body of Lieutenant Grenfell, and carrying it off from among the enemy. He is the eldest son and heir of Major-General Viscount Frankfort de Montmorency, while his mother is the daughter of a Field-Marshal.”

Another article published by the Black and White Budget the day after his death reported the following: ”While the Colonial division was thus employed on the right front of the Illrd division, which on the 11th February numbered approximately 5,300 officers and men, Lieut.-General Gatacre ordered a reconnaissance on the 23rd February, to ascertain the truth of rumours that, in consequence of Lord Roberts’ invasion of the Free State, the Boers were falling back from Stormberg. Five companies of the Derbyshire with one machine gun, and the 74th and 77th batteries, Royal Field artillery (four guns each), were posted north of Pienaar’s Farm, while the mounted troops, numbering about 450, and consisting of De Montmorency’s Scouts, four companies mounted infantry, and a party of Cape Mounted Rifles, were ordered to scout to the front as far as the height overlooking Van Goosen’s Farm, and to try to lure the enemy towards the position occupied by the guns and the infantry. The scouts were fired on from a ridge held by the burghers; their advance was checked, and General Gatacre, finding that the Boers were not to be tempted forward, ordered a general withdrawal. The reconnaissance was not effected without loss. About 10.30 a.m. Captain the Hon. R. H. L. J. De Montmorency, V.C., 21st Lancers, had mounted a small kopje, accompanied by Lieut. -Colonel F. H. Hoskier, 3rd Middlesex Volunteer artillery, Mr. Vice, a civilian, and a corporal, when sudden fire at short range was poured into the little party, and De Montmorency, Hoskier and Vice were killed. This was not at once known to those behind, who for a time were left without orders. The enemy’s fire was so heavy that until 3.30 p.m. it was impossible to extricate the remainder of the scouts. The losses in De Montmorency’s small corps were two officers and four rank and file killed, two rank and file wounded, one officer and five other ranks missing, of whom two were known to have been wounded. The result of the day’s operations, in Lieut.-General Gatacre’s opinion, tended to show that the enemy’s force at Stormberg had diminished”

The units strength was about 100 and over the next three months they constantly received praise from Major Pollock and others writing about the operations in the central Cape Colony. In a skirmish near Stormberg at Dordrecht in the Cape Colony on 23rd February 1900, Montmorency was killed in action. It is said that he fired 11 shots after being mortally wounded.

Montmorency is buried in the Molteno Cemetery in the Chris Hani District Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa. For more details see Find a Grave.

Lieutenant the Hon. Richard Frederick Molyneux

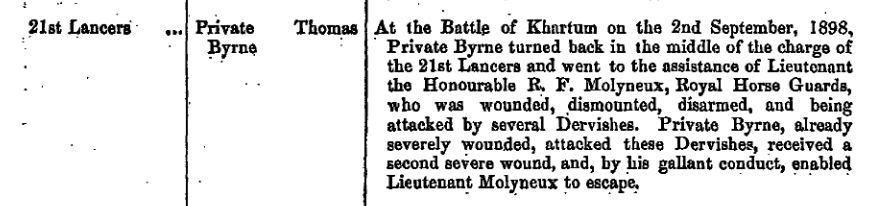

As mentioned previously, both Kenna and Montmorency were friends of Lieutenant the Hon. Richard Frederick Molyneux of the Royal Horse Guards, and it was himself that was involved in the action for which the Lancers 3rd Victoria Cross was awarded to Private Thomas Byrne during the Battle of Omdurman.

During the charge of the 21st Lancers, Byrne turned back to go to the assistance of Lieutenant the Hon.R F Molyneux of the Royal Horse Guards who had been dismounted from his horse, wounded and was being attacked by several Dervishes.

In the book “The River War: an Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan”, Churchill describes the incident as follows: Major Crole Wyndham had his horse shot under him by a Dervish who pressed the muzzle of his rifle into its hide before firing. From out of the middle of that savage crowd the officer fought his way on foot and escaped in safety. (Note this was the incident in which Captain Paul Kenna received his VC for rescuing Wyndham) Lieutenant Molyneux fell in the Khor into the midst of the enemy. In the confusion he disentangled himself from his horse, drew his revolver, and jumped out of the hollow before the Dervishes recovered from the impact of the charge. Then they attacked him. He fired at the nearest, and at the moment of firing was slashed across the right wrist by another. The pistol fell from his nerveless hand, and, being wounded, dismounted, and disarmed, he turned in the hopes of regaining, by following the line of the charge, his squadron, which was just getting clear. Hard upon his track came the enemy, eager to make an end. Best on all sides, and thus hotly pursued, the wounded officer perceived a single Lancer riding across his path. He called on him for help. Whereupon the trooper, Private Byrne, although already severely wounded by a bullet which had penetrated his right arm, replied without a moment’s hesitation and in a cheery voice, ‘All right Sir!’ and turning, rode at four Dervishes who were about to kill his Officer. His wound, which had partly paralysed his arm, prevented him from grasping his sword and at the first ineffectual blow it fell from his hand, and he received another wound from a spear in the chest. But his solitary charge had checked the pursuing Dervishes. Lieutenant Molyneux regained his squadron alive, and the trooper, seeing that his object was attained, galloped away, reeling in his saddle. Arrived at his troop, his desperate condition noticed and was told to fall out. But this he refused to do, urging he was entitled to remain on duty and have ‘another go at them’. At length, he was compelled to leave the field, fainting from loss of blood.”

It was for this action that Private Byrne was awarded the Lancers third Victoria Cross of the day. Again, like both Kenna and Montmorency, Private Byrne served in the Second Boer War and returned to England afterwards. He died on 5th March 1944 and is buried in Canterbury City Cemetery in Kent.

Molyneux also served in South Africa and was A.D.C. to Lord Errol. He went on the officers’ Reserve list in 1904 but at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 he was re-employed on active service with his regiment and fought in France and Belgium in 1914 and 1915.

After the war he finally retired from the army in 1919 with the rank of Major upon which he was appointed groom in ordinary to King George V and began his long and happy connection with the Royal Family which ripened as the years went by into close friendship. He was the groom in waiting to King George from 1933 to 1936 and in 1935 was created K.C.V.O. (Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order).

After the death of King George V in 1936 he became, until her own death, extra equerry to Queen Mary, whose interests “he shared to the full.

Sir Richard Molyneux was unmarried and lived in Berkeley Square, London. He died 20th January 1954 at the age of eighty. His funeral took place at Kirkby on 23rd January.

Melton Mowbray had become a ‘mecca’ for the aristocracy and sporting gentlemen taking part in foxhunting. At the time, it was just as important to be seen hunting at Melton Mowbray as it was to appear at the best Society Balls in London.

Kenna and Montmorency, along with Molyneux were just three of the many dozens of military officers that frequented Melton during the hunting seasons. Kenna and Montmorency must have made an impact on the town for them to be recognised with the VC flower beds being designed in their honour.