In todays current climate when people are struggling with mental health issues due to the lockdown initiated as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, I take a look at the slang phrase “Going Doolally” and its origins.

Traditionally when British soldiers struggle to pronounce foreign place names, they anglicise them or call them something simple and easy to remember, Ypres on the Western Front during WW1 was known as “Wipers” and Ploegsteert became Plugstreet. Doolally is no exception as this was the soldiers’ name for the Deolali transit camp.

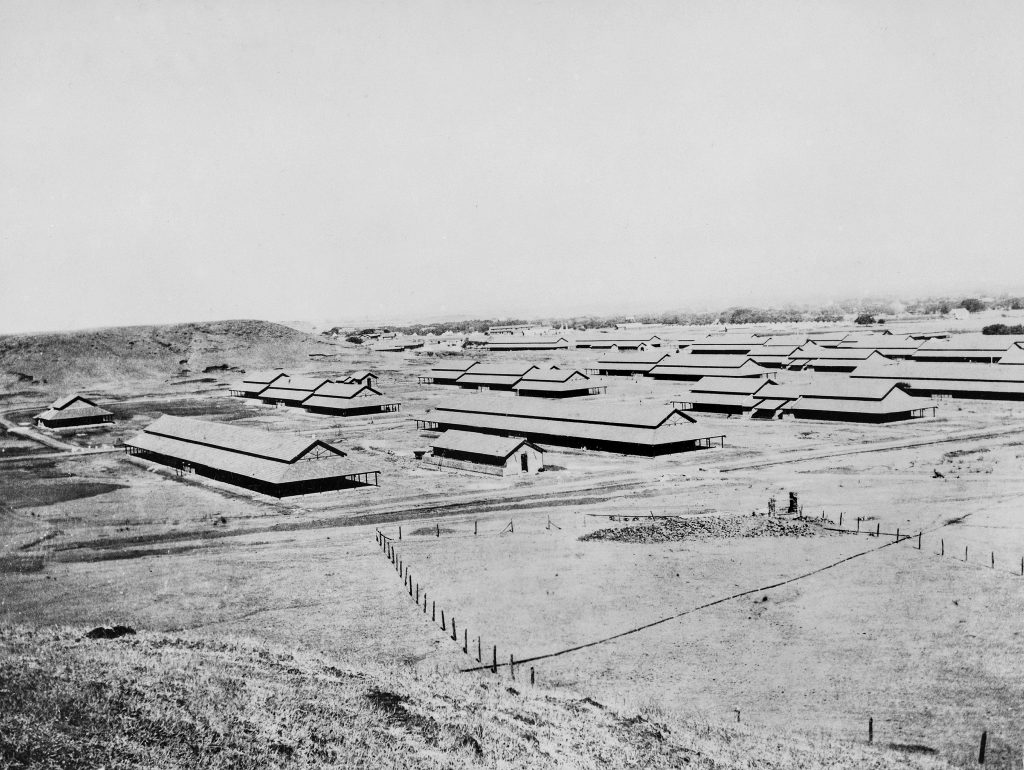

Established in 1861, the Deolali transit camp was a British Army transit camp in Maharashtra, India. It was in use throughout the time of the British Raj, the rule by the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent until they gained Independence from Britain in 1947.

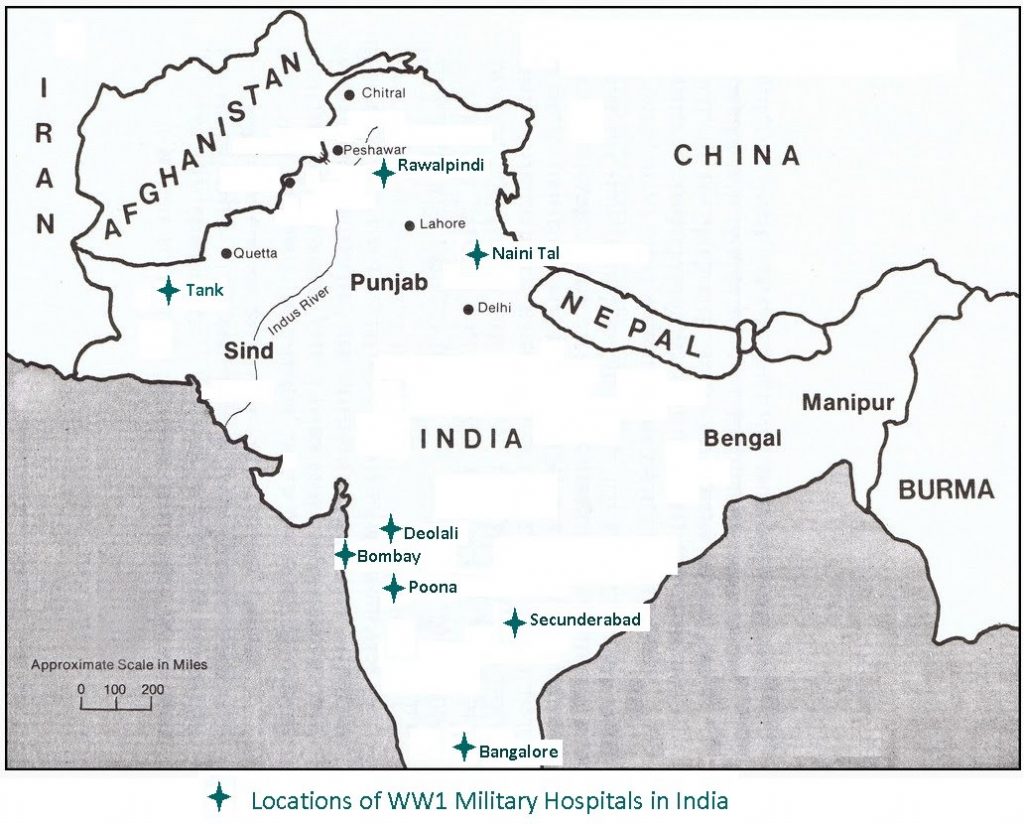

The camp was located near Deolali, Maharashtra, around 100 miles North East of Bombay (or Mumbai as it is known today). The camp is situated near a prominent conical hill and the Bahula Fort.

The camp housed soldiers that were newly arrived in the country and those awaiting ships to take them back home to Britain.

For those awaiting to be shipped back home, they were disarmed and allocated light duties with little else to occupy the men.

It was said that soldiers who were waiting to be shipped back home, often had a long wait for a troop ship to take them back home.

The camp was often full by the end of summer with soldiers awaiting troop ships. New arrivals in this period often had to sleep on the floor owing to a lack of beds and suffered from sand flea bites.

Conditions in the camp were said to be poor especially for those stationed there for long periods. As a side effect of having little to do at the camp, combined with the heat of the long Indian summers drove many a soldier a little crazy and hence the phrase “Going Doolally” was coined and the term “doolally” became a slang term associated with mental illness. It is a contraction of the original form “Doolally tap”, where the latter part is derived from “tapa”, meaning fever” in Hindustani and “heat” or “torment” in Sanskrit.

The whole phrase is perhaps best translated as “camp fever”. The term was in use from the late 19th century and the contracted form was dominant by the First World War.

Soldiers could spend time in the nearby city of Nasik which offered numerous gin bars and brothels and consequently diseases such as venereal disease was common amongst the troops.

Also common in the Deolali area was Malaria, which can affect the brain. This remained a major issue for the British Army right through the Second World War despite the development of anti-malarial drugs.

Suicides in the camp were not uncommon. Despite its reputation the Deolali area actually has a milder climate than nearby Mumbai (Bombay) or Pune, though it was known to be incredibly dusty in the period leading up to the monsoon.

The camp had a sanatorium (military hospital) but, despite its reputation, there was never a dedicated psychiatric hospital there. Cases of mental illness were instead confined to the military prison or sent to dedicated hospitals elsewhere in the country.

The camp was also used for training and acclimatisation for soldiers newly arrived in British India. New drafts would stay at the camp for up to several weeks carrying out route marches and close order drill to get used to the hotter climate.

During the First World War it was used as a hospital for prisoners of war held in other camps in India, including Turks taken prisoner on the Mesopotamian campaign and German soldiers.

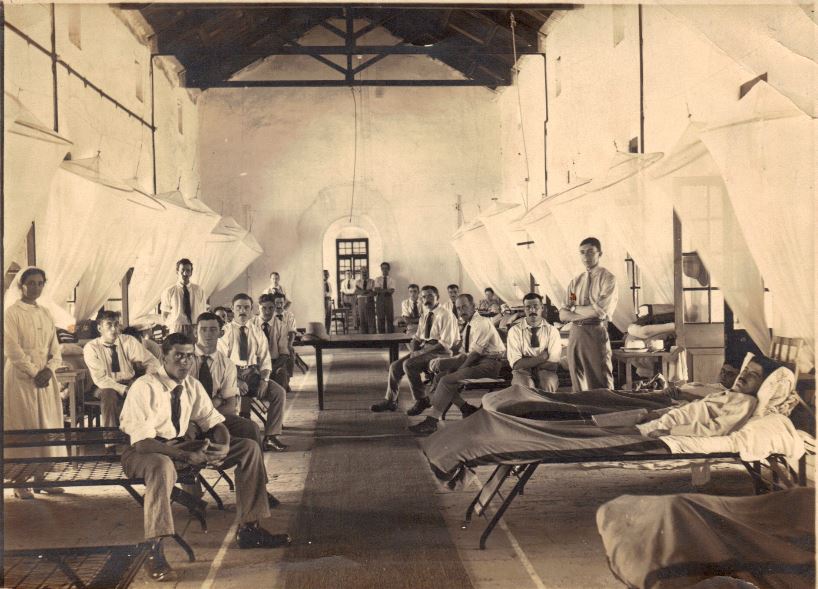

The hospital complex consisted of old barracks, stone bungalows and galvanised iron huts spread over a large area nearly two and a half kilometres long by one kilometre wide. Housing over 2000 beds, the nurses cared for patients with diseases such as malaria, smallpox, Spanish influenza and cholera, in trying climatic conditions. Such conditions were too much for some nurses, such as Staff Nurse Emily Clare, who succumbed to Spanish Influenza on 17 October 1918.

Margaret Walker Bevan was born in Swansea on 22 October 1883, the elder of two daughters to John and Harriet Bevan. In May 1902 she became a trainee nurse in Coventry City Hospital. On completion of her basic training, she joined the Becket Hospital in Barnsley, rising to the position of Matron by the time she resigned in 1915.

She joined the Welsh Military Hospital, Netley (near Southampton) in July 1915, volunteering for overseas service. The hospital, maintained by voluntary contributions from Wales, had 399 beds and was treating casualties of the Great War within weeks of the British Expeditionary Force crossing the channel in 1914.

In May 1915 the Commanding Officer received orders to take the Welsh Hospital overseas to India as a complete unit with staff and equipment for 3000 beds. It was known as the 34th Welsh General Hospital, Deolali, India, and the nursing staff had to join The Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS).

En route to India the personnel had three weeks stay at Alexandria where most of the nursing staff did temporary duties at various Military Hospitals. Around 20 June they landed at Bombay and were sent up in small numbers to Deolali as hospital wards were prepared. Margaret was put in charge of a ward of 70 beds, treating troops who had served in Basra.

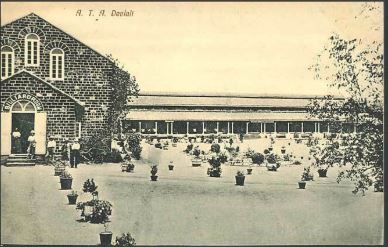

Later wounded Turkish prisoners of war were sent to that section. This photograph was taken in May 1917 and shows Ward 11 in the hospital in Deolali, with Margaret standing on the left hand side.

Another Nurse serving at the 34th Welsh Genera Hospital was Australian Vera Agnes Margaret Paisley was born in Bunbury, Western Australia in December 1892. She was a certified nurse on enlistment in the Australian Army Nursing Service on 8 May 1917, serving until 12 November 1919.

She had previously worked for three years at the Perth Public Hospital. Embarking for service in India from Fremantle on 5 June, with the rank of staff nurse, Paisley reached Bombay on 18 June. On arrival she was posted to 34th Welsh General Hospital at Deolali, almost 260 kilometres from Bombay.

As well as the 34th Welsh, there was also the 44th British General Hospital and there was also a RAMC depot there.

The camp had a military prison that was used for soldiers of the British Army and, during the Second World War, for captured Indian nationalists who had served in the Japanese-founded Indian National Army.

During the Second World War the camp also boasted cinemas, swimming pools, amusement parks and restaurants for the troops.

No 159 Squadron with their Liberator Mk I bombers were based at RAF Deolali from 24th May 1942 to 1st June before moving onto RAF Chakrata.

No 656 Air Observation Post (AOP) Squadron was also at Deolali the OC Denis Coyle was told he would have to find and train all his own replacement pilots, which required his setting up an AOP Training School in Deolali, India, staffed and run by his own Squadron personnel, spreading his already limited resources ever more thinly. This school was only partially successful, providing only eight pilots from two AOP courses, before he changed tack and formed 1587 (Refresher) Flight, which instead provided jungle training and theatre familiarisation for newly-qualified pilots sent out from the AOP School in the UK.

After the Indian Independence in 1947, the camp was transferred to the Indian Army and was used as an artillery school and depot for at least 10 artillery and service corps units. It also hosted an army records office and an aerial observation squadron.

During the period leading up to independence the camp was known as the “Homeward Bound Trooping Depot” and was used to return large numbers of British troops and their families back home as British forces withdrew from the country under the scheme known as PYTHON

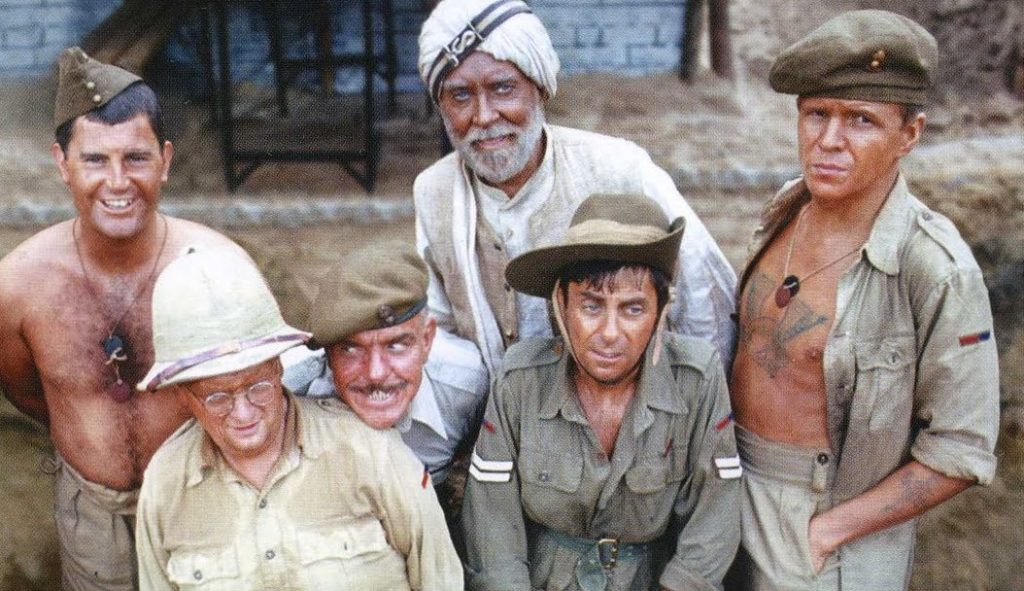

In the 1970s, the BBC sitcom series It Ain’t Half Hot Mum was produced about a Royal Artillery concert party based at Deolali Camp.