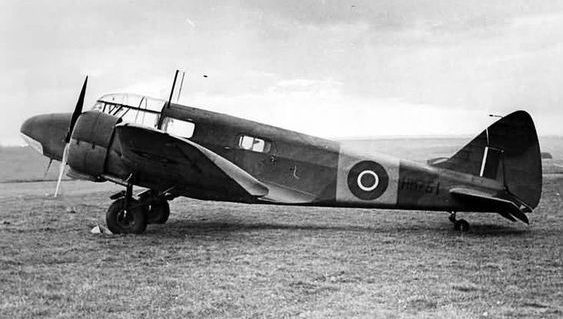

On the 13th August 1944, a Wellington bomber took off at 15:45Hrs from RAF Market Harborough for what was thought to be just another trip, a routine cross country training flight followed by a bombing detail at Grimsthorpe Bombing Range.

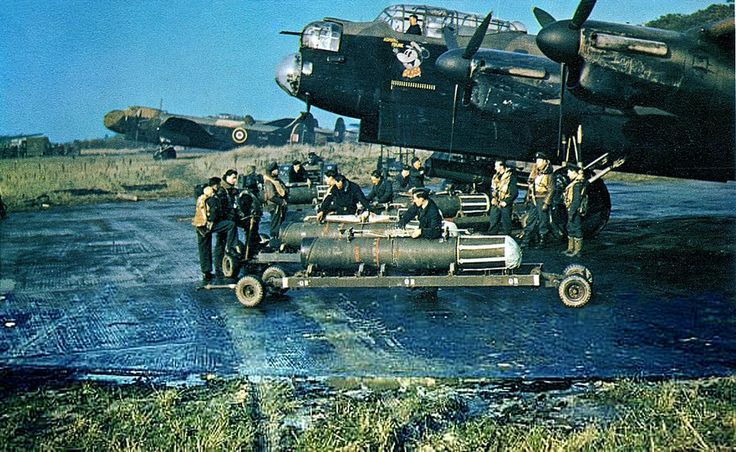

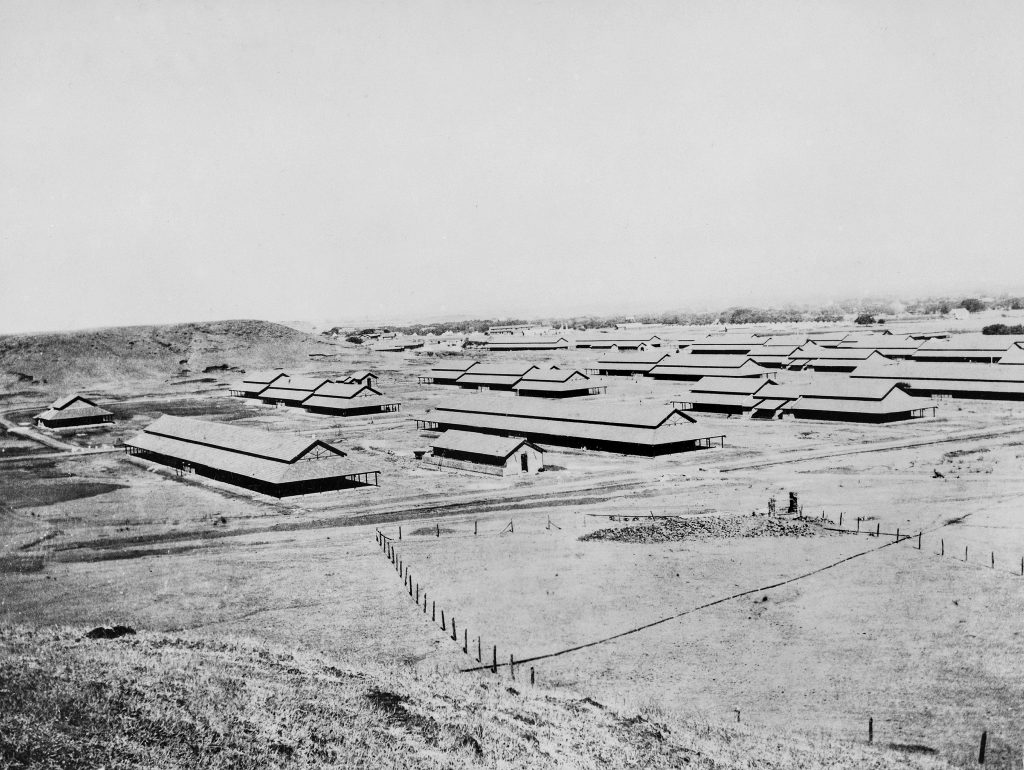

The aircraft in question was a Wellington Mk X, serial number LN281 operated by No 14 Operational Training Unit (OTU).

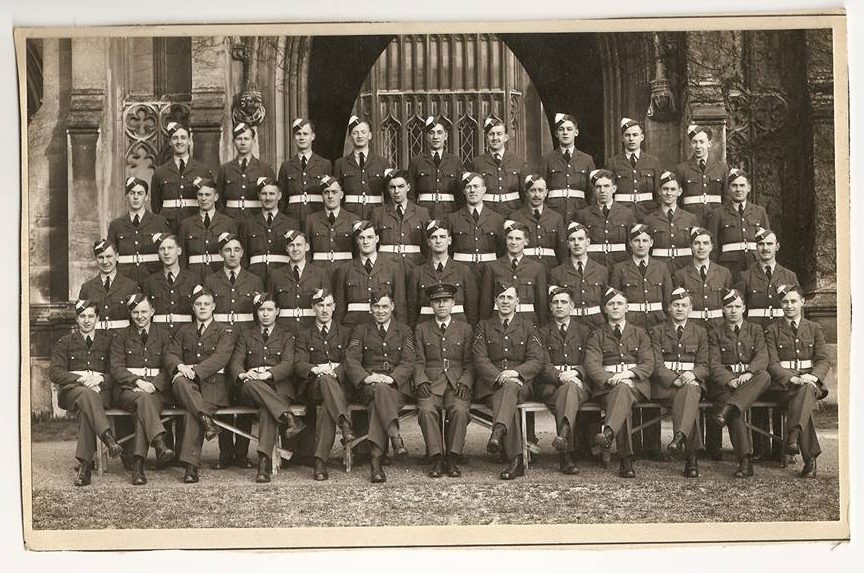

The primary role of the OTU was to train aircrew to fly ‘medium’ twin engined bombers to an acceptable standard before joining an operational squadron.

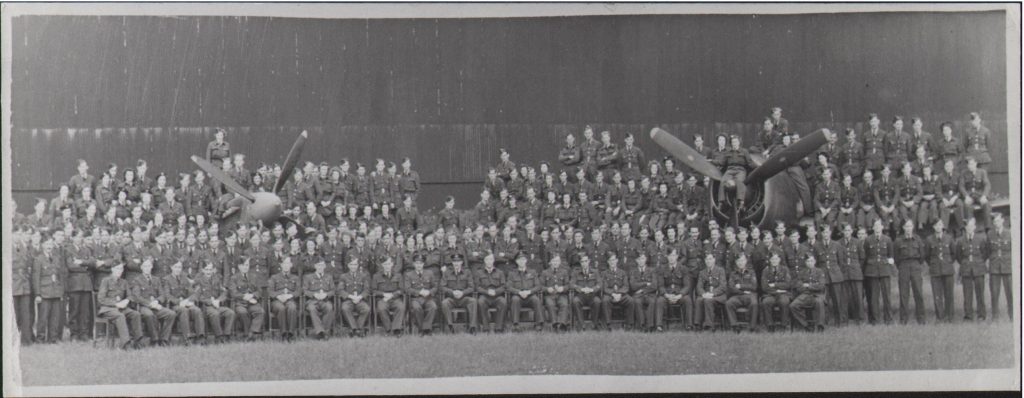

No 14 OTU was originally formed at RAF Cottesmore in Rutland on 8th April 1940 when No 185 Sqn merged with the Station Headquarters flight. Its role was to train night bomber crews equipped with Hampdens and Herefords.

In recognition of the units’ achievements in training aircrew, an official badge for No 14 OTU was approved by King George VI. The badge depicted a hounds head with a hunting horn and riding whip. The badge design was based on the units location and role.

Originally being formed at Cottesmore in Rutland followed by a move to Market Harborough in Leicestershire, both counties are known to be some of the best hunting grounds in the country.

The role of the unit was the training of airmen whose duties are to hunt and destroy the enemy. The Motto ‘Keep With The Pack’ was selected because ‘concentration had long been a principle in Bomber Command and the airmen hunt in packs not only for securing greater defence but to obtain increased effect in bombing.

In the autumn of 1942, No. 14 OTU converted from the Hampden bomber onto Wellingtons and remained at Cottesmore until August 1943 when it was moved to Market Harborough.

The OTU courses lasted five months and involved 80 Flying Hours. Bomber Harris, C in C Bomber Command explains in his book ‘Bomber Offensive’ that training at OTUs only comes right at the end of a long period of flying training for each individual. The education of a member of a Bomber Crew was the most expensive in the world, costing some £10,000 for each airman, enough to send 10 men to Oxford or Cambridge University for 3 years.

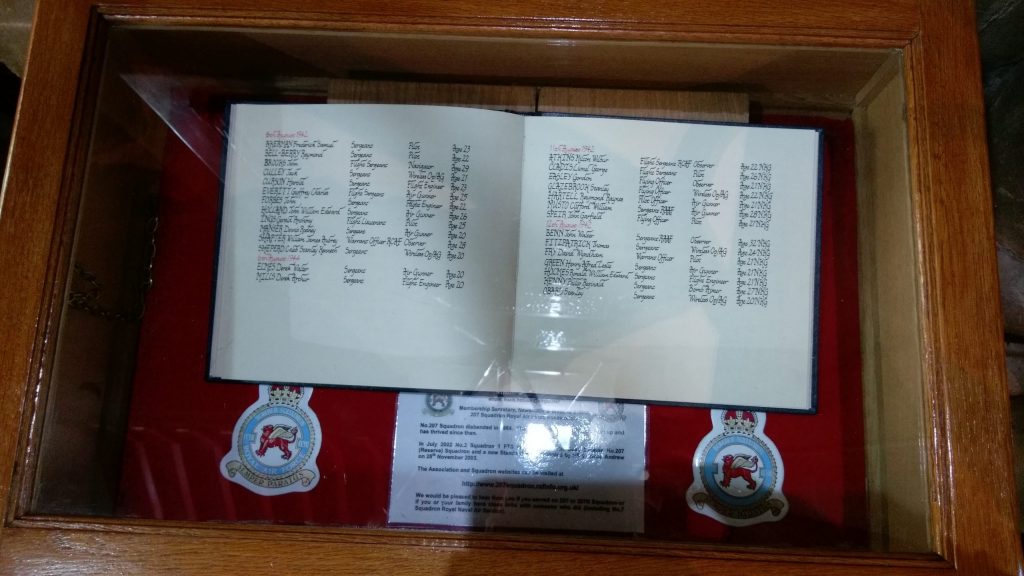

Official records show that the total number of trained personnel output from No. 14 OTU whilst at Market Harborough was 516 Pilots, 484 Navigators, 480 Bomb Aimers, 497 Wireless Operator/Air Gunners and 931 Air Gunners. In order to achieve this output, flying took place on 510 days and 372 nights, during which a total of 45,835 Flying Hours were achieved. In the course of these training exercises, a total of 61 aircrew were to make the ultimate sacrifice due to being killed in training accidents, with dozens more wounded.

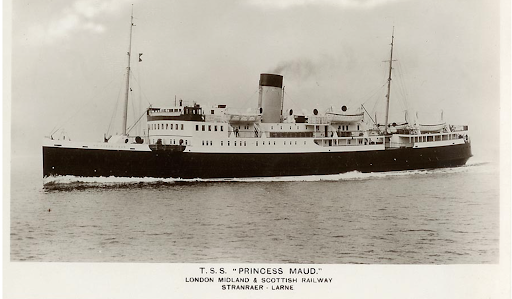

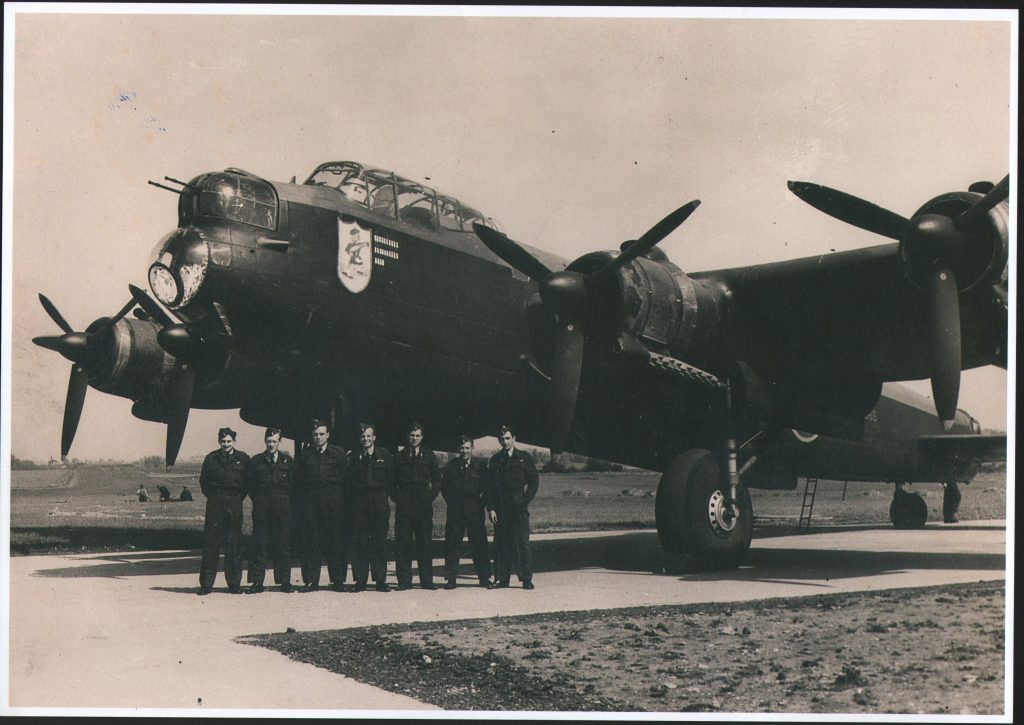

As mentioned above, the Wellington on this ‘ordinary trip’ was built to contract B124362/40 by Vickers Armstrong’s Ltd at Chester and delivered to MU store in October 1942 with the Serial Number LN281. Following delivery, it was issued to No 429 Squadron at RAF East Moor just north of York in early June 1943 and given the code AL-V for Victor.

Not long after being delivered to 429 Sqn, LN281 ‘V for Victor’ was taking part in her first operational sortie and was tasked with bombing Wuppertal, Germany.

This attack was aimed at the Elberfield half of Wuppertal as the other half had been attached at the end of May. This particular raid involved 630 aircraft from Bomber Command consisting of 251 Lancasters, 171 Halifaxes, 101 Wellingtons, 98 Stirlings and 9 Mosquitoes. A total of 34 aircraft were lost on the raid, 10 Halifaxes, 10 Stirlings, 8 Lancasters and 6 Wellingtons.

Post war analysis show that 94% of the Elberfield part of Wuppertal was destroyed that night with 171 industrial premises and 3,000 houses being destroyed, and a further 53 industrial premises and 2,500 houses being severely damaged. The loss of life is thought to be approximately 1,800 killed and 2,400 injured.

Canadian, P/O Keith McLean Johnston was the pilot in charge of ‘V for Victor’ and her multi-national crew when they took off from East Moor at 23.08hrs on 24th June 1943.

The crew consisted of: Pilot – P/O Keith McLean Johnston RCAF (J/16067), of North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Navigator – Sgt Howard William Clarke RCAF, of Talbot, Alberta, Canada. Bomb Aimer – Sgt F W R Frost RAF (1320228). Wireless Operator/Air Gunner – Sgt Joseph Arthur Marcel Lortie RCAF, of St Agathe des Monte, Quebec, Canada. Rear Gunner – Lt J C Elliott USAAF.

At 03.54hrs the LN281 was landing on return from the mission when a tyre burst, followed by the undercarriage collapsing resulting in both propellers, the starboard wing, starboard engine and the bomb doors becoming damaged.

It is unclear as to whether or not this was due to damage received by enemy night fighters or flak defences. As a result of damage sustained, the aircraft was taken out of active service to undergo repairs.

The aircraft was repaired in works and on completion of the repair it was issued to No 14 OTU at RAF Market Harborough in late-1943.

On the 13th August 1944, LN281 was tasked with a routine cross country training flight followed by a bombing detail at Grimsthorpe Bombing Range – Just Another Trip!

The normal crew of a Wellington would consist of the Pilot, Navigator, Wireless Operator, Air Gunners (x2) and Bomb Aimer. At times Staff Pilots and Navigators would be additional crew members as their role was to train the inexperienced crew and ‘check them out’ ensuring that the trainees were achieving the correct standard. Staff Pilots and Navigators were deemed to have enough experience due to recently completing a tour of ops at a front line Squadron, normally consisting of 30 sorties over enemy territory.

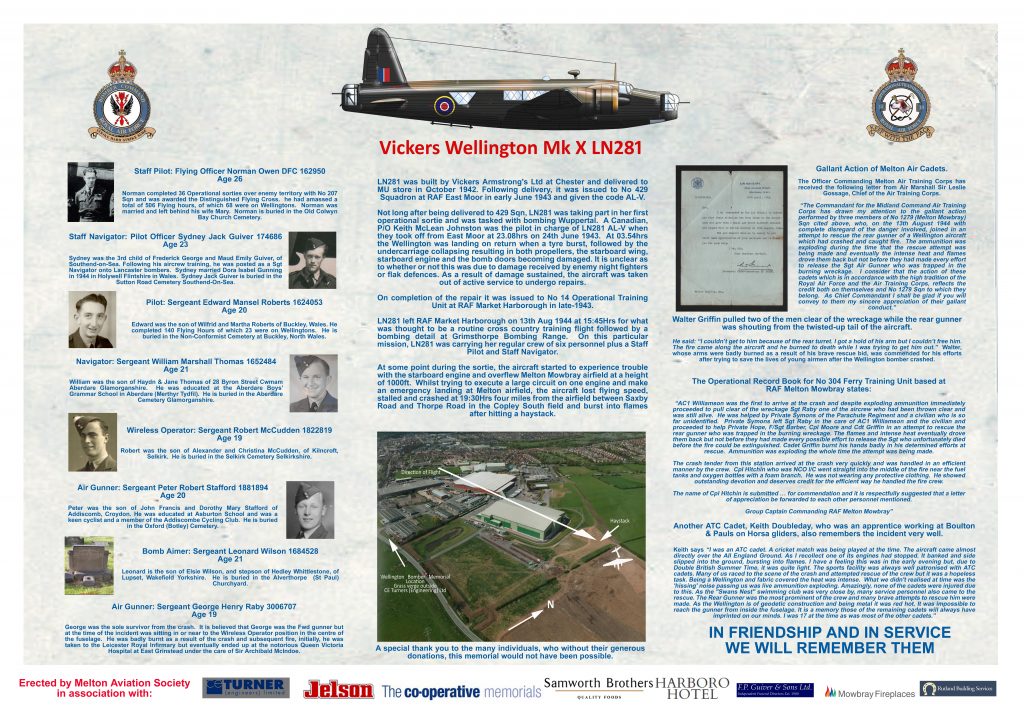

On this trip, the crew for LN281s training mission was no exception as the crew consisted of the usual six trainees plus a staff Pilot and Navigator.The crew of LN281 on the 13th August was: Staff Pilot: Fg Off N Owen DFC 162950 Staff Nav: Plt Off S J Guiver 174686 Pilot: Sgt E M Roberts 1624053 Nav: Sgt W M Thomas 1652484 W/Op: Sgt R McCudden 1822819 Bomb Aimer: Sgt L Wilson 1684528 Air Gunner: Sgt P R Stafford 1881894 Air Gunner: Sgt G H Raby 3006707

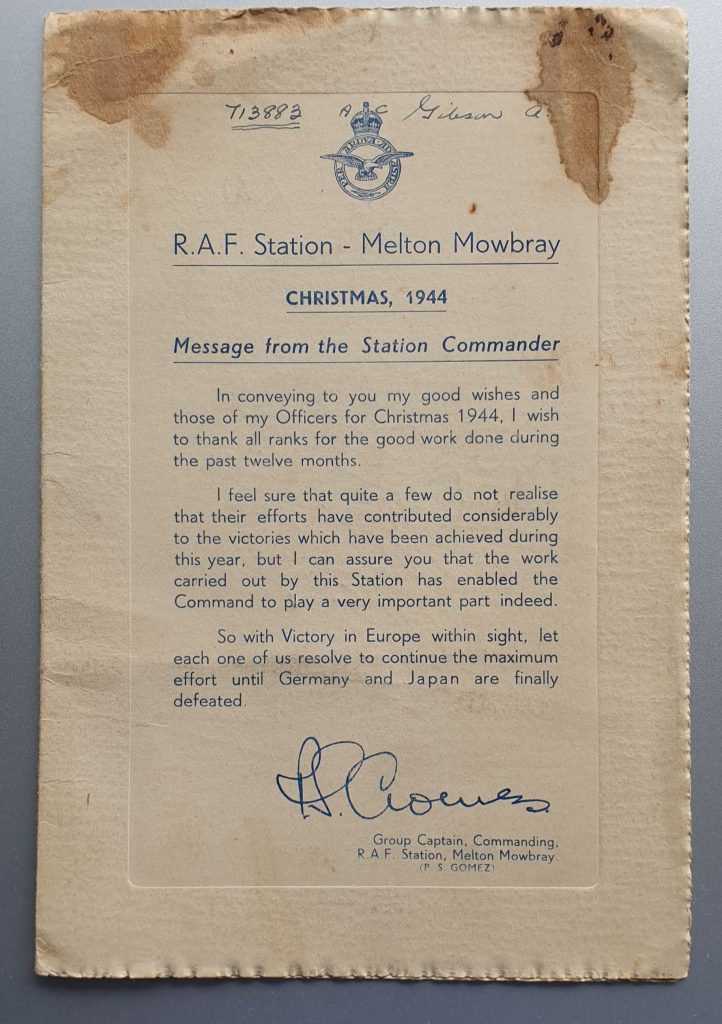

At some point during the sortie, the aircraft started to experience trouble with the starboard engine and overflew RAF Melton Mowbray airfield at a height of 1000ft.

At this height, the aircraft was too low for the crew to safely bale out so the only option was to try and make a safe landing.

Whilst trying to execute a large circuit on one engine and make an emergency landing at Melton airfield, the aircraft lost flying speed, stalled and crashed four miles from the airfield between Saxby Road and Thorpe Road in the Copley South field and burst into flames.

The entry in the No 14 OTU ORB for 13th August states:- “Wellington LN281 crashed 4 miles north Melton Mowbray airfield. Staff Pilot – F/O Owen. Pupil Pilot – Sgt. Roberts. Attempted forced landing in field and blew up on impact, finally being destroyed by fire. 7 killed and 1 dangerously injured.”

The accident record card for LN281 goes on to state “The aircraft crashed and caught fire. Court of Inquiry: the aircraft started to execute a large circuit on one engine, lost flying speed, stalled and crashed and burnt out” ” Pilot lost safe S.E. flying speed and turned with the good engine and stalled”.

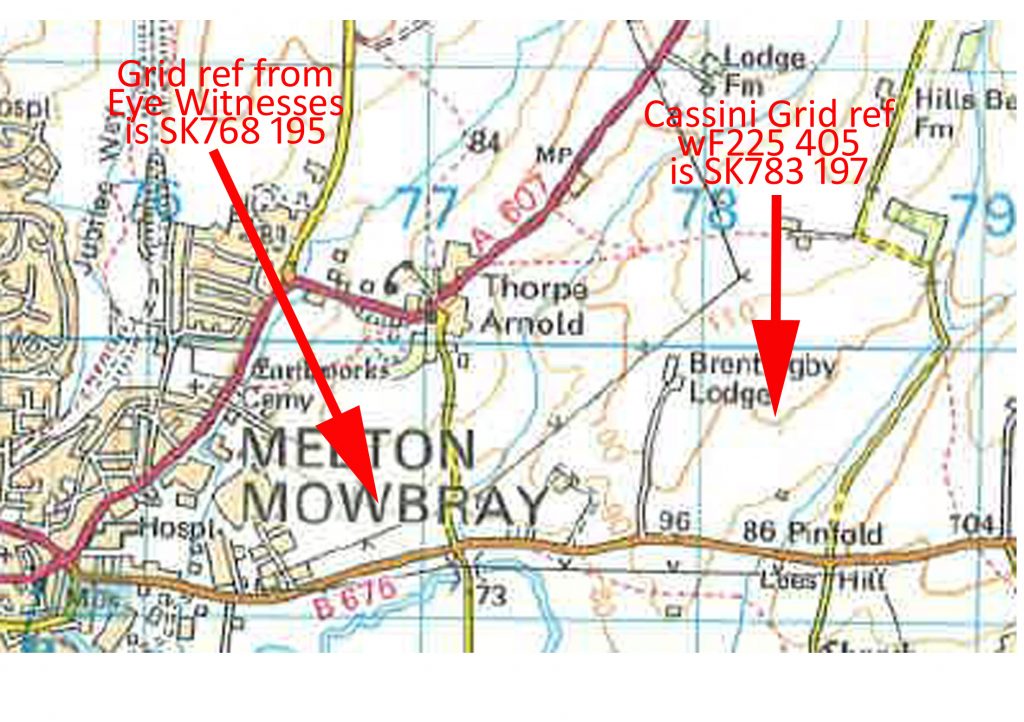

The official records state that LN281 crashed in a field known as Copley South which is approximately 4 miles north of RAF Melton Mowbray airfield and quoted the following Cassini map grid reference WF 225405 Sheet 630 and this equates to an Ordnance Survey map reference of SK783 197.

However, according to eye witness accounts, and the actual location of Copley South field, the crash site is at grid reference SK768 195, several hundred yards further West than the Cassini reference.

As one can imagine with this type of incident taking place in a well-populated town, there would have been numerous witnesses that saw the incident or are relatives of those who were involved in it some way or another.

The following paragraphs detail a few of those accounts of local people that witnessed the event or became involved in the rescue.

The Melton Times from Thursday October 4th 2012 reported the following: It was around 19:30Hrs when Melton man Walter Griffin spotted the aircraft pass overhead with 1 propeller feathered just clearing the houses in Saxby Road whilst he was playing cricket at the All England Ground on Saxby Road. At the time Walter was an air cadet and went to the rescue with two other fellow cadets.

Walter said: “I thought it might crash because it only had one engine going. When I got to the crash site the Wellington was broken in half and it had caught fire straight away.”

“There were three airmen on the ground. One was very badly burnt, another was alive and the other one I didn’t know.”

Walter pulled two of the men clear of the wreckage while the rear gunner was shouting from the twisted-up tail of the aircraft.

He said: “I couldn’t get to him because of the rear turret. I got a hold of his arm but I couldn’t free him. The fire came along the aircraft and he burned to death while I was trying to get him out.”

It wasn’t long before more people soon arrived at the scene to help in trying to rescue the crew.

Walter, whose arms were badly burned as a result of his brave rescue bid, was commended for his efforts after trying to save the lives of young airmen after the Wellington bomber crashed.

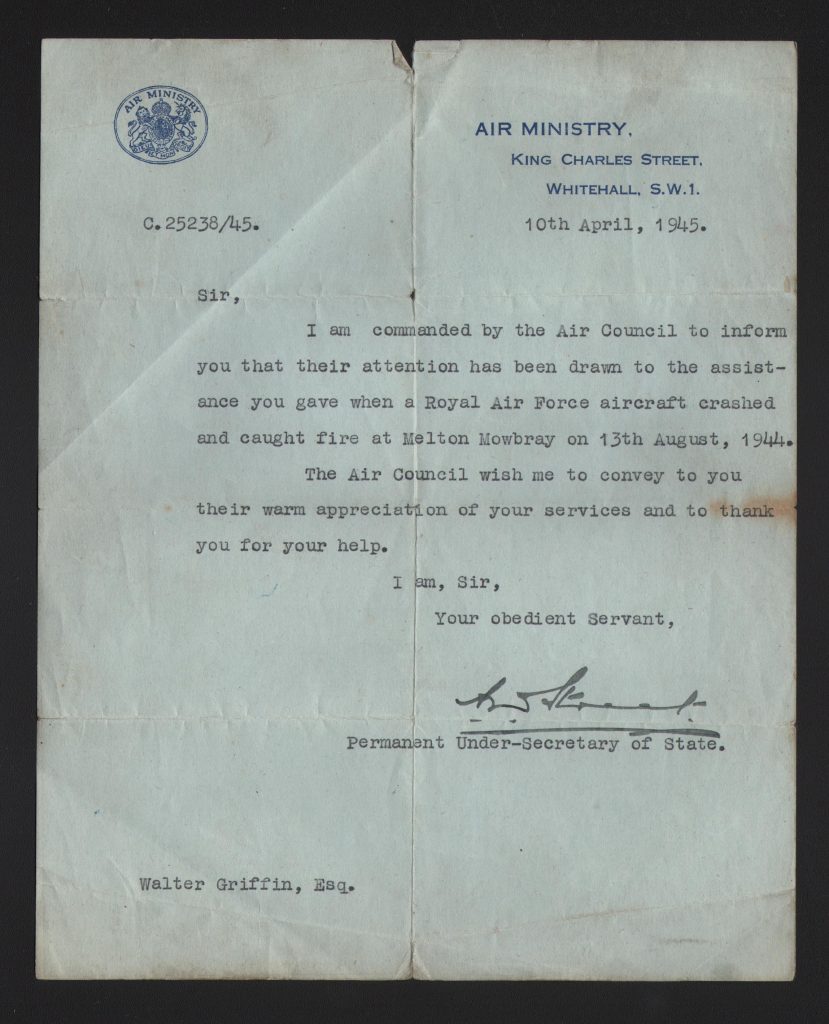

“Sir, I am commanded by the Air Council to inform you that their attention has been drawn to the assistance you gave when a Royal Air Force aircraft crashed and caught fire at Melton Mowbray on 13th August 1944. The Air Council wish me to convey to you their warm appreciation of your services and to thank you for your help. I, am Sir, Your Obedient Servant Permanent Under Secretary of State”

The following statement is an extract from The Melton Times dated Friday October 6th 1944.

Gallant Action of Melton Air Cadets.

The Officer Commanding Melton Air Training Corps has received the following letter from Air Marshall Sir Leslie Gossage, Chief of the Air Training Corps.

Flt/Sgt R.S. Baber, Cpl Moore and Cdt W. Griffin.

“The Commandant for the Midland Command Air Training Corps has drawn my attention to the gallant action performed by three members of No 1279 (Melton Mowbray) Sqn cited above, who, on the 13th August 1944 with complete disregard of the danger involved, joined in an attempt to rescue the rear gunner of a Wellington aircraft which had crashed and caught fire. The ammunition was exploding during the time that the rescue attempt was being made and eventually the intense heat and flames drove them back but not before they had made every effort to release the Sgt Air Gunner who was trapped in the burning wreckage. I consider that the action of these cadets which is in accordance with the high tradition of the Royal Air Force and the Air Training Corps, reflects the credit both on themselves and No 1279 Sqn to which they belong. As Chief Commandant I shall be glad if you will convey to them my sincere appreciation of their gallant conduct.”

Another ATC Cadet, Keith Doubleday, who was an apprentice working at Boulton & Pauls on Horsa gliders, also remembers the incident very well.

Keith says “I was an ATC cadet. A cricket match was being played at the time. The aircraft came almost directly over the All England Ground. As I recollect one of its engines had stopped. It banked and side slipped into the ground, bursting into flames. I have a feeling this was in the early evening but, due to Double British Summer Time, it was quite light. The sports facility was always well patronised with ATC cadets. Many of us raced to the scene of the crash and attempted rescue of the crew but it was a hopeless task. Being a Wellington and fabric covered the heat was intense. What we didn’t realised at time was the ‘hissing’ noise passing us was live ammunition exploding. Amazingly, none of the cadets were injured due to this. As the “Swans Nest” swimming club was very close by, many service personnel also came to the rescue. The Rear Gunner was the most prominent of the crew and many brave attempts to rescue him were made. As the Wellington is of geodetic construction and being metal it was red hot. It was impossible to reach the gunner from inside the fuselage. It is a memory those of the remaining cadets will always have imprinted on our minds. I was 17 at the time as was most of the other cadets.”

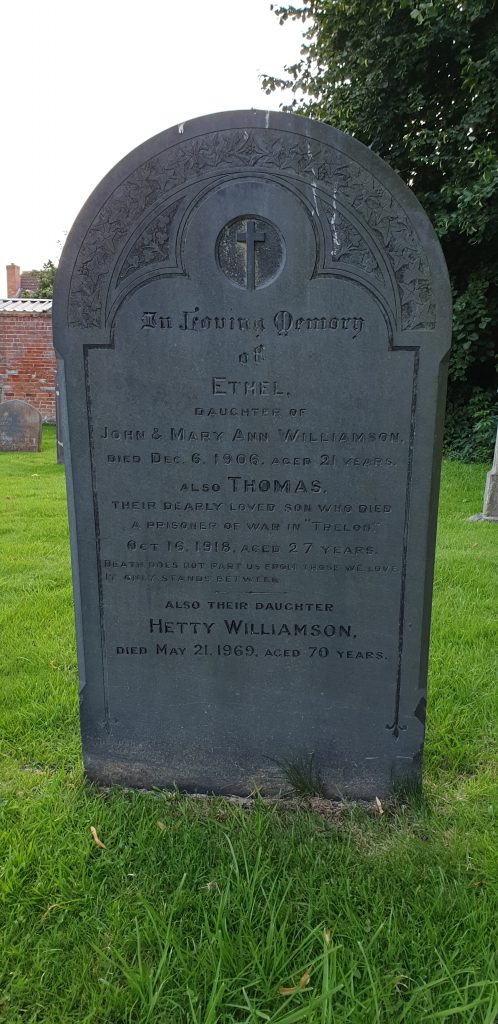

Jack Williamson was an airman stationed at RAF Melton Mowbray and was known as ‘Snowy’ while at Melton as his hair was jet black. Jack remembers being asked to work late one night by his Chief as a Sqn of Fleet Air Arm Swordfishes came into Melton for an overnight stay. Jack was a witness to the Wellington that crashed between Thorpe Arnold and Saxby Road on August 13th 1944. Jack remembers thinking ‘What’s he doing flying away from the airfield with one prop feathered?’ when it hit a haystack and burst into flames. Jack was one of the first people to arrive at the incident and managed to drag one of the crew members out of the flames. As the RAF Ambulance and medics arrived at the scene, Jack said to one of them ‘look after this chap a minute’ and crept away from the scene as he didn’t want any publicity for his actions. After the accident, everybody was asking who was this brave airman was but nobody knew. A couple of days later back at camp, all the airmen were getting inspected as it was the CO’s parade and Jack was picked up as his uniform was all burnt from rescuing the crewman. From this they deduced that Jack must have been that airman whom they were searching for and he was subsequently awarded a citation for his heroism.

Another eyewitness to the crash was a gentleman called Ken Digby. Ken was just 12 at the time and was one of the first on the scene. In an article published in The Melton Times on 25th October 2012, he said “I can remember it vividly to this day and will never forget what he saw.”

Ken recalls: “I lived at Thorpe End and was walking near the Swan’s Nest with a friend and saw the plane flying low. We ran across the road and could see smoke pouring out as it crashed near to Copley’s South field. As we entered the field a gentleman called Jack Gibbs came up to us and told us to keep away. There was ammunition on board and bullets were going off in all directions. We saw one of the airmen trying to get out of the cockpit but all of a sudden it just went up in flames.”

Ken went on to say that Trevor Woods, the fireman in charge, gave him some money to go and get some beer for his crew and he went to the White Hart in Melton to fetch it.

He said: “My dad got some Toddy’s Ale and I carried it back down to the gate to give it to the firemen.

Another witness to the crash was a Mrs Orridge of Melton who recalls the crash in a Melton Times article on the 4th Jan 2013:

“My friends and I stood on a bridge spanning the railway line and we watched a Wellington bomber circling above.

It came so low we could clearly see the men in the plane and we started waving to them.

Suddenly, to our horror, the plane was alongside the bridge, almost touching, the noise was horrendous. It vanished from sight. Then a loud explosion and smoke told us the plane had crashed.

That day remains with me still and the sadness we felt.”

Ron Barrow was swimming with his friend Derek Woodman in the River Eye at the Swans Nest or Chippy Dixons Lido as it was also known. Ron remembers the Wellington circling round, maybe upto 3 times before it crashed in the ‘100 acre’ field.

Ron and Derek rushed over to the site but as they were only in their swimming trunks there was not a lot they could do as the aircraft was already engulfed in flames. They returned to the Swanns nest with sore feet from all the thistles in Copley South field.

Rons main recollection of the crash was the smell of burnt flesh that stayed with him for several days after the crash. When asked about the position of the aircraft, he recalls that the fuselage was broken in two with the tail part angled up in the air.

Back in the early 70’s, a young Melton man named Joe Perduno had been discussing the crash with another witness called George Charity. As a result of being told the rough area where the crash occurred, Joe went metal detecting and found an aircraft fuel gauge which he remembers the words “Rear Tank 160 Gallons”.

Back in the early 70’s, a young Melton man named Joe Perduno had been discussing the crash with another witness called George Charity.

As a result of being told the rough area where the crash occurred, Joe went metal detecting and found an aircraft fuel gauge which he remembers the words “Rear Tank 160 Gallons”.

In an interview on 30th October 2013, Roy Beeken was 20 at the time of the crash recalls the incident vividly.

Roy explained to me his version of events. Roy worked part time for the Melton Fire Service and was at home on the Kings Road ‘extension’ when the Wellington flew overhead in a North West – South Easterly direction flying low over the houses on Thorpe Road with one engine smoking and getting lower and lower all the time. He didn’t see it crash, but saw the smoke rising up from the scene.

Roy kept his fireman’s uniform at home and instead of reporting to the fire station, he put on his fireman’s tunic and got on his bicycle and went to the site of the crash. As he was cycling down Saxby Road (B676) he was passed the Melton fire tenders.

Roy recalls running away from the burning aircraft as the oxygen cylinders were exploding and also remembers the same as Ron Barrow in that the tail part of the aircraft was angled slightly up from the ground.

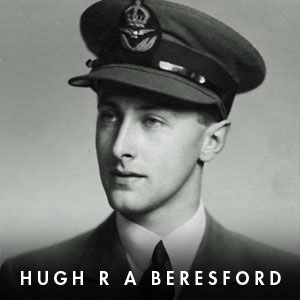

Staff Pilot: Flying Officer Norman Owen DFC 162950

Norman Owen was born in 1918 and was the son of Richard and Diana Owen, of Colwyn Bay, Wales. He grew up on Pendared Farm, Llysfaen, with his sister and five brothers and was educated at the local primary school, probably in Llysfaen and then from 1929 – 1932 at Colwyn Bay Central School.

Prior to joining the RAF, Norman served as a constable with London Metropolitan Police from 1937 – 1941, serving at Hammersmith throughout the Blitz.

Following the outbreak of war he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on the 14th May 1941 as an Aircraftman 2nd Class Aircrafthand/Pilot and allocated service number 1390425. He trained as a pilot at Turner Field, Georgia, USA and completed his training in Britain. He was promoted to temporary Sergeant on 13th December 1942 after which he was commissioned on 23rd November 1943. During his flying training he sometimes took a detour to fly over Pendared Farm, where his mother would wave a sheet which led to some local complaints about low flying!

Following completion of training Norman was posted to No 207 Squadron at RAF Spilsby, Lincolnshire where he completed a full operational tour of 30 operational sorties as a Lancaster pilot. It was normal procedures that after completing an operational tour, the crew would then be posted to training units for a rest tour and sometimes this required the crew to be split up. Norman was transferred to No 14 OTU at RAF Market Harborough, Leicestershire to become an instructor. Approximately a month after leaving 207 Sqn at Spilsby

Norman completed 36 operational tours over enemy territory with No 207 Sqn, Norman was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and this was announced in the Supplement to the London Gazette dated 13th October 1944 page 4693. However, as DFCs cannot be awarded posthumously, the Gazette stated that the award will take place with effect 12th August 1944.

Norman’s first operational trip over enemy territory was a “2nd Dickie” trip with an experienced crew before taking his own crew on 35 ops. Some were to French targets, which until late May 1944 were deemed to count as only a third of an op. Norman is amongst several pilots recorded in 207’s ORB as complaining about this. After the losses on the Mailly raid in May 1944 the powers-that-be relented and French trips were then re-counted as a whole op. However, by the time Norman was nearing the end of his tour the number of required ops had been raised to 35 and this continued until near the end of the war when the number of 1st tour ops were changed down and up several times, presumably as a surplus of aircrew arose due to the training programme output, and the reducing losses then being seen.

At the time of the crash, Norman had amassed a total of 506 Flying Hours, of which 68 were in Wellingtons. He was aged 26 when he died and left behind his wife Mary Owen, of Dolwen.

Many thanks to Normans nephew, Raymond Glynne-Owen who has provided valuable information and photographs regarding Norman.

Flying Officer Norman Owen DFC is buried in Grave 34 of the C of E Section at Old Colwyn Church Cemetery.

Staff Navigator: Plt Off Sydney Jack Guiver 174686

Sydney Guiver was born in 1921 in the Rochford region of Essex and was the 3rd child of Frederick George and Maud Emily Guiver, of Southend-on-Sea. Prior to joining the RAF Volunteer Reserve in September 1941 as trainee aircrew, Sydney was a bank clerk.

Following his aircrew training, he was posted as a Sgt Navigator onto Lancaster bombers.

According to the Supplement to the London Gazette dated 30 May 1944, Sydney’s promotion from NCO aircrew to Commissioned Officer was announced. The entry stated that he was appointed to Commission within the General Duties branch and was awarded the rank of Pilot Officer on probation (emergency) wef 31st Mar 44.

Sydney married Dora Isabel Gunning in 1944 in Holywell Flintshire in Wales. Dora served in The Land Army and they lived with Frederick and Maud at 641 Southchurch Road, Southend-On-Sea. Although they lived in Southend, Sydneys death certificate recorded his address as Bryn Awel, Leeswood, Mold, Flintshire.

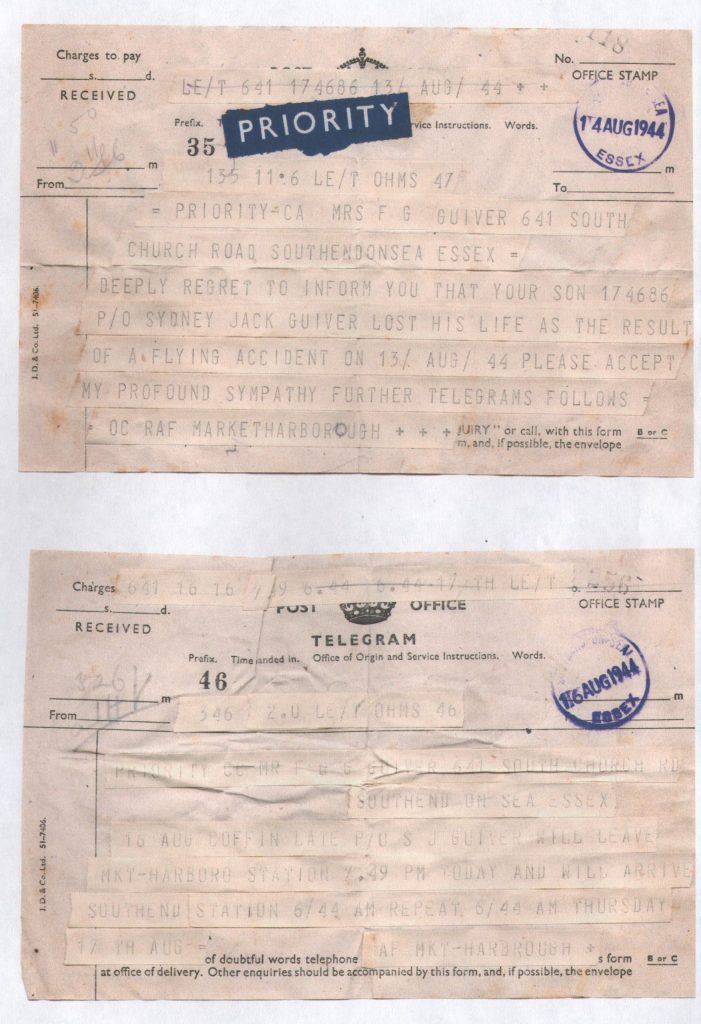

Two telegrams sent to Mrs GF Guiver informing her of the death of her son and when the coffin will be dispatched from RAF Market Harborough.

The first telegram reads:

“Mrs F G Guiver, 641 South Church Road Southend on Sea, Essex. Deeply regret to inform you that your son 174686 P/O Sydney Jack Guiver lost his life as a result of a flying accident on 13/Aug/44. Please accept my profound sympathy further telegrams follows OC RAF Market Harborough.”

The 2nd telegram advises the family about the coffin and reads: “16 Aug Coffin late P/O S J Guiver will leave Mkt-Harboro Station 7.49PM today and will arrive Southend Station 6/44AM repeat 6/44AM Thursday 17th August – RAF Market Harborough.”

This letter was sent to Sydneys father on the 20th Aug and reads:

“Dear Mr Guiver, I write with the deepest regret to convey to you the feelings of this unit in the very sad loss of your son, Pilot Officer Sydney Jack Guiver, as the result of a flying accident.

Your son was the Navigator of an aircraft which crashed near Melton Mowbray at approximately 7.30pmon the 13th August 1944. Death was instantaneous.

During the short time your son was at this Unit he made himself very popular with everyone. The loss to the service is great as the Royal Air Force can ill afford to lose such a keen and cheerful member of aircrew.

I have today written to your sons wife, giving full particulars of her husband’s death.

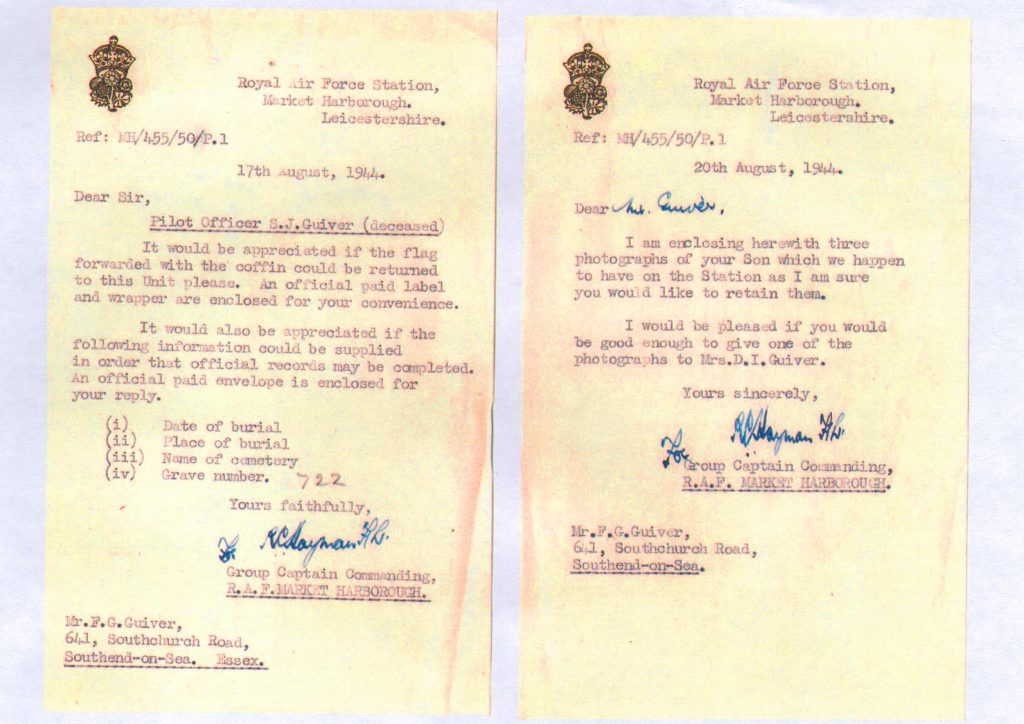

Again on the 17th & 20th Aug, RAF Market Harborough wrote to the father. The letter on the 17th reads:

“Dear Sir,

Pilot Officer S J Guiver (deceased)

It would be appreciated if the flag forwarded with the coffin could be returned to this Unit please. An official paid label and wrapper are enclosed for your convenience.

It would be appreciated if the flag forwarded with the coffin could be returned to this Unit please. An official paid label and wrapper are enclosed for your convenience.

Date of burial

Yours faithfully Group Captain Commanding RAF Market Harborough”

The 2nd letter from the 20th reads:

“Dear Mr Guiver, I am enclosing herewith three photographs of your son which we happen to have on the Station as I am sure you would like to retain them.

I would be pleased if you would be good enough to give one of the photographs to Mrs D I Guiver.

Yours Sincerely

Group Captain Commanding

RAF Market Harborough”

Pilot Officer Sydney Jack Guiver is buried in Plot C Grave 722 in the Sutton Road Cemetery Southend-On-Sea.

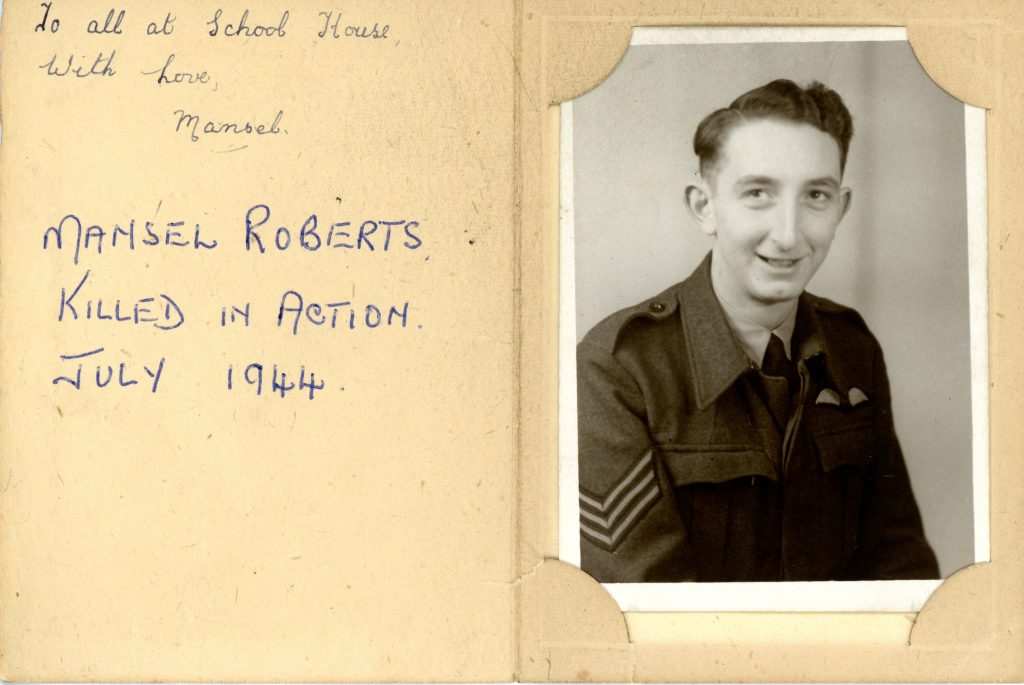

Pilot: Sgt Edward Mansel Roberts 1624053

Edward Mansel Roberts joined RAF (Volunteer Reserve). He was the son of Wilfrid and Martha Roberts of Buckley, Wales

Edward Mansel Roberts completed 140 Flying Hours of which 23 were on Wellingtons. He was aged 20 when he died.

Sgt Edward Mansel Roberts is buried in the Non-Conformist Cemetery at Buckley.

Navigator: Sgt William Marshall Thomas 1652484

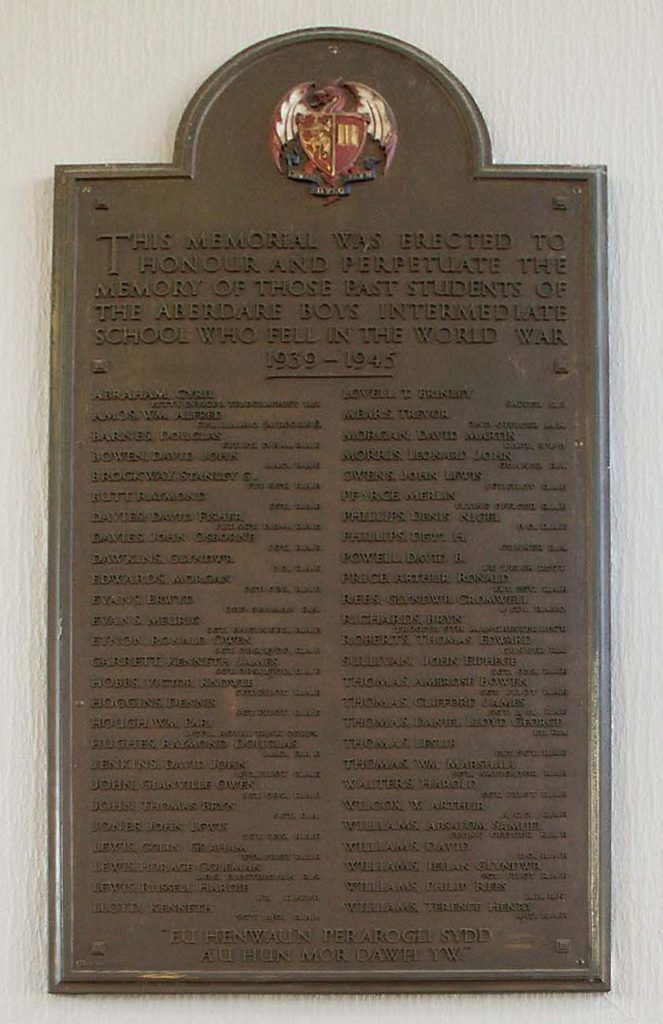

Sgt Thomas was the son of Haydn & Jane Thomas of 28 Byron Street Cwmam Aberdare Glamorganshire and was born in 1923 in Aberdare (Merthyr Tydfil).

He was educated at the Aberdare Boys’ Grammer School where he is commemorated by name on the schools’ Memorial Plaque, dedicated to those who fell in the Second World War.

The wording on the memorial plaque states:

“This memorial was erected to honour and perpetuate the memory of those past students of the Aberdare Boys Intermediate School who fell in the World War 1939-1945.”

“Thomas, Wm Marshall Sgt Navigator RAF”

Sgt William Marshall Thomas is buried in an unconsecrated Grave X/4120 at Aberdare Cemetery Glamorganshire.

Air Gunner: Sgt Peter Robert Stafford 1881894

Sgt Peter Stafford was born on 29th Aug 1923 in Croydn, Surrey to John Francis and Dorothy Mary Stafford, of Addiscombe. He was educated at Asburton School and was a keen cyclist and a member of the Addiscombe Cycling Club. Prior to joining the RAF he was an electrician serving with the Borough Valuer’s Dept in Croydon.

A letter from his RAF Station said that after being posted there on the 28th June 1944, he had made himself most popular with everyone there and carried out his duties with keenness and efficiency, an example to all of them who knew him. The family were obviously devastated at the time, and his mother always maintained that this event largely contributed to her husband’s death from cancer in 1948.

Sgt Peter Robert Stafford is buried in Plot H/3. Grave 124 of the Oxford (Botley) Cemetery. Botley is a RAF regional cemetery used during the Second World War by RAF stations in Berkshire and neighbouring counties.

Bomb Aimer: Sgt Leonard Wilson 1684528

Son of Elsie Wilson, and stepson of Hedley Whittlestone, of Lupset, Wakefield.

Sgt Leonard Wilson is buried in Grave 374 Section. T of the Alverthorpe (St Paul) Churchyard.

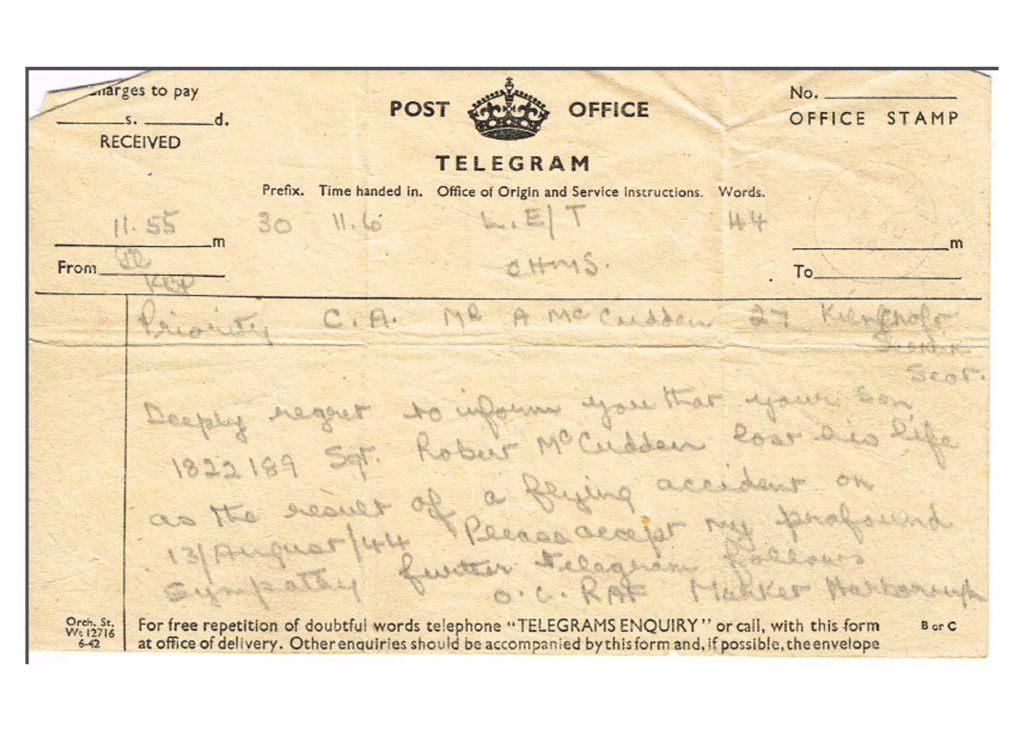

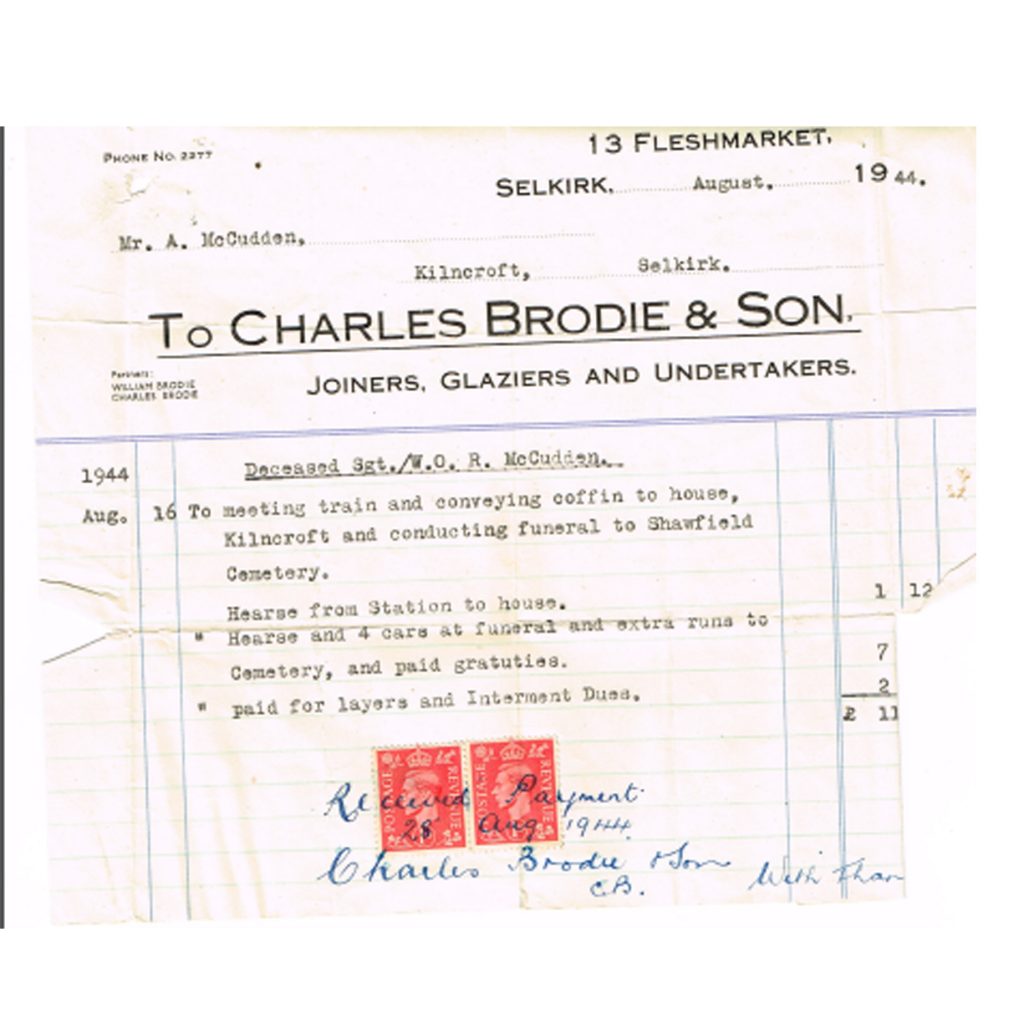

W/Op: Sgt Robert McCudden 1822819

Robert McCudden was born in 1925 and was the son of Alexander and Christina McCudden, of Kilncroft, Selkirk.

He joined No 427 Squadron Air Training Corps in December 1941 and according to a newspaper report he was very quiet and self effacing. He applied himself most diligently to his instruction and overcame his handicap of leaving school early.

Prior to joining the RAF, he was employed at Ettrick Mills where he was very popular among his fellow workers.

Robert joined the RAF in May 1943, training first of all as a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner and later as a Sergeant (Signals).

Sgt Robert McCudden was buried in Section. H. Grave 2108 at the Selkirk Cemetery on the 18th August 1944 and his old ATC Squadron, No 427 Sqn, provided the Escort Party under the Command of P/O Beattie with Cadets aalso acting as pall-bearers.

Air Gunner: Sgt George Henry Raby 3006707

Sgt. George Henry Raby was the sole survivor from the crash. It is thought that George was the Fwd gunner but at the time of the incident was sitting in or near to the Wireless Operator position. During the flight he said he either did not plug in his intercom as he never heard the pilot say anything about a problem, he did not have his harness on and just went to sleep and woke up in hospital.

George was badly burnt as a result of the crash and subsequent fire. Initially, George was taken to the Leicester Royal Infirmary but eventually ended up at the notorious Queen Victoria Hospital at East Grinstead under the care of Sir Archibald McIndoe.

George, who naturally underwent numerous operations for many years afterwards. On a recent trip to hospital for a cataract op, George bumbed into a nurse who remembered him from 30 odd years ago when he had some more surgery at the old Norwich Community Hospital. Although he has never spoken about the incident, he reeled off some details to the nurse about the crash. Apparently, after he was in East Grinstead Hospital, an RAF investigation team came every day to speak to him but was sent packing by Sir Archibald McIndoe and they never came back.

George passed away in Norwich on 29th August 2015 aged 90.

Melton Mowbray Wellington Bomber Memorial Unveiling & Dedication Service

During 2013 and 2014, I had the pleasure of leading the Wellington Bomber Memorial fundraising project with the aim of raising a target amount of £2,500 to erect a memorial to recognise both the sacrifice of the bomber crew, but also those local individuals who bravely attempted the rescue effort.

By the start of August 2014, a sum of £3, 399 had been raised.

Mowbray Fireplaces provided the granite for the plaque which the company have very generously donated free of charge. Richard Barnes Funeral Directors and Co-Operative Memorials offered to engrave the plaque but again to do it free of charge, and finally the memorial was built by Rutland Building Supplies. On the rear of the memorial is a display board printed by B&H Midland Ltd and housed in a wooden frame built by Bob Cox, sadly no longer with us.

The unveiling and dedication service took place on Sunday 17th August 2014 at 14:00 Hours.

Cadets from No 1279 (Melton Mowbray) Sqn and No 2248 (Oakham) Sqn along with the Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire, Mayor of Melton Mowbray, Defence Animal Centre RAF Police and Leicestershire Constabulary.

Standard Bearers from the Melton Mowbray, Leicester & Oakham Royal Air Forces Association Branches and the Melton Mowbray Royal British Legion and Royal British Legion Womens Section were also in attendance.

Following the welcome speech and history of the tragedy, Air Marshall Sir ‘Dusty’ Miller gave a small speech on the history of No 14 OTU and Bomber Command. A Cadet SNCO from No 1279 Sqn gave a small talk on the involvement of the Melton Mowbray 1279 Sqn Air Cadets and the crash and subsequent rescue attempts.

After the speeches, the Dedication Service delivered by the Padre / Vicar was followed by a Wreath Laying ceremony, the Last Post, and the National Anthem.

After the event, refreshments were served at the RAF Association Club on Asfordby Road.