In my previous blog Melton & District Spitfire Fund I looked at how the people of Melton Mowbray and surrounding villages came together in a fundraising effort in late 1940 to buy a Spitfire fighter plane.

This blog continues with the story of the Melton Mowbray & District Spitfire P8522 and looks at its history from being built in 1941 right through to when it was retired from RAF service in 1945.

Spitfire P8522 was built according to the official Air Ministry list as a F Mk 1A, but during production it was converted to a F Mk IIB. P8522 was built in April 1941 at the Vickers Armstrong Ltd. factory at Castle Bromwich, and was part of Contract No B981687/39/C.23(C) dated 12th April 1939 which was placed for the first batch of 1000 F MkII’s.

As requested by the fund organisers, P8522 was adorned with the towns emblem of the Red Lion Rampant upon a white background and wore the title “Melton Mowbray & District” along the side of the fuselage under the windscreen.

On the 5th May 1941, P8522 took her maiden flight at Castle Bromwich with the Vickers test pilot Alex Henshaw at the controls.

Shortly afterwards on 12th May 1941, P8522 was transferred to No 24 Maintenance Unit at RAF Tern Hill in Shropshire where it went to be fully fitted out for operational duties.

Following being fitted out for operation duties, P8522 was transferred to No 303 (Polish) Sqn based at RAF Northolt on the 19th June 1941 and assigned to “B” Flight with the code RF-W. In addition to the codes RF-W, the 303 Squadron emblem was also added next to the Melton lion.

Rolling off the production line in 1941 meant that the Melton Mowbray & District Spitfire was too late into service to be involved in the Battle of Britain and it joined No 303 Squadron which claimed the largest number of aircraft shot down during the Battle, even though it joined the Battle two months after it had begun.

No. 303 Squadron RAF was formed in July 1940 in Blackpool, England before deployment to RAF Northolt on 2 August as part of an agreement between the Polish Government in Exile and the United Kingdom. It had a distinguished combat record and was disbanded in December 1946.

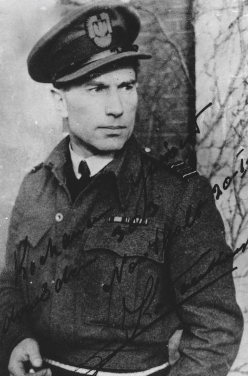

Flying Officer Wojciech Kolaczkowski was the first Polish pilot to fly the Melton Spitfire when on the 20th & 21st June he took P8522 up for a series of test flights to check it out before being declared operational on 303 Sqn.

The first operational flight came on the 24th June when Sgt Stanislaw Belza took P8522 to Martlesham Heath as part of “B” Flight which had been tasked with fighter escort duties protecting bombers on a raid over occupied Europe. This operation proceeded to plan except for haze over the target area.

Belza again took P8522 on ‘Escort Duties’ the following day but this time, the Squadron encountered severe flak and were engaged in a number of dog fights with ME.109s. The first sortie of the day was at 06:10 Hrs for an hour, landing back at 07:10. Sgt Belza was again airborne in the Melton Spitfire at 11:40Hrs for another escort sortie, landing back at base at 13:40Hrs.

Later in the day, P8522 was again airborne for her 3rd sortie of the day, again escorting bombers. This time Kolaczkowski was at the controls and took off at 15:40Hrs and returned to base at 17:25Hrs.

On the 26th June, B Flight moved to Martlesham Heath at 07:30Hrs. P8522 was piloted again by Kolaczkowski for the 35 minute flight.

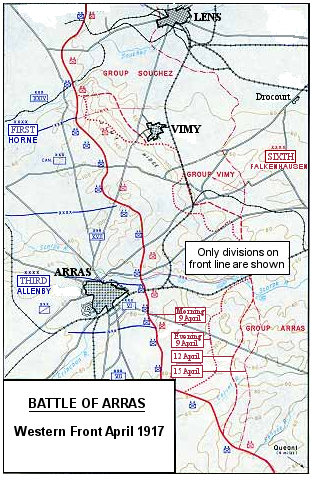

They had gone to Martlesham Heath to take part in Circus operations where bomber attacks with fighter escorts took place during day time. The attacks were against short range targets with the intention of occupying enemy fighters and keeping their fighter units in the area concerned.

Kolaczkowski took off in P8522 at 11:00Hrs escorting 23 Blenheim bombers on a raid to Comines power station. The weather conditions over Commines made bombing impossible due to 10/10 cloud over France so the bombers turned back and the fighters encountered no opposition and returned to base, landing at 12:25Hrs.

The 27th was a rather hectic day for 303 Sqn, with weather conditions making a morning circus impossible so the Squadron went on a mass Rhubarb operation resulting in various Messerschmitt’s being damaged or destroyed on the ground.

A Rhubarb operation is when sections of fighters or fighter-bombers, taking full advantage of low cloud and poor visibility, would cross the English Channel and then drop below cloud level to search for opportunity targets such as railway locomotives and rolling stock, aircraft on the ground, enemy troops and vehicles on roads.

P8522 was not involved in the days Rhubarb taskings, but later in the day Kolaczkowski was at the controls of P8522 again for escort duties, initially going to Manston at 1600Hrs. At 20:30Hrs he took off as part of B Flight providing escort duties for 23 Blenheims as part of the Circus 25 operation to bomb the steel works at Lille. Minor skirmishes took place with one enemy aircraft being damaged by F/O Zumbach, but no action for P8522.

Kolaczkowski was again flying P8522 on the 28th providing escort high cover for 24 Blenheims attacking Comines as part of the Circus 26 Op. Just West of Comines, he was in a dog fight with 5 Messerschmitt Me-109s. In his combat Kolaczkowski report stated:

“After a prolonged dog-fight with with 5 ME 109’s west of Comines, I had come down low and near Desvres was joined by Sgt Belc. Flying across the aerodrome I fired a short burst at a Me.109 which was mounted on trestles. The aircraft collapsed amid a cloud of smoke.

Rounds fired: 7 rounds each of 2 cannon, 15 rounds each of 4 M/G”

On the 30th, P8522 RF-W was again part of the fighter escorts with F/L Jankiewicz at the controls providing escort for another Circus bombing trip for 18 Blenheims atacking the Pont-a-Vendin Power Station in France, but this time there was nothing special to report.

Kolaczkowski was back in control of P8522 on the 1st July when they carried out a couple of evening bomber escorts over France with all aircraft returning safely.

The second combat victory for Kolaczkowski and P8522 occurred on the 2nd July 1941 when 303 & several other Fighter Sqn’s were on escort duties again from Martlesham as part of a Circus Op to the Fives/Lille steel and engineering works at Lille. No opposition was met until they were over the target area and a series of dog fights developed. Some fighters stayed with the bombers whilst others became involved with the fighters.

The Fives/Lille steel and engineering works at Lille was to be the target of several attacks carried out by the RAF and USAAF bombers during the war.

The Operations Record Book entry for the 2nd July states “F/Lt Kolaczkowski attacked two Me’s who were attacking the bombers; one was destroyed by the Blenheim and the other by F/Lt Kolaczkowski. F/O Zumbach shot down 1 Me in flames and damaged others. P/O Lipinski attacked and probably destroyed another Me109. Sgt Wojciechowski was wounded in the shoulder but returned to Martlesham suffering from loss of blood. It transpired later that he had shot down one Me109 in a series of dog fights. S/Ldr Lapkowski was missing from this operation and it was thought that he had collided with another Spitfire belonging to Sgt Gorecki. This transpired to be incorrect as Gorecki was picked up three days later after 74 hours in Channel. There has been no further news of S/Ldr Lapkowski.”

According to the personal combat report that Kolaczkowski submitted, the attack took place in an area from Lille to mid-channel at around 12:45Hrs.

“As soon as we had reached Lille Me.109’s began to engage our Squadron and the other escort Squadrons, and the dog-fights continued until we had reached mid-channel. During the many engagements which took place between 15,000 and 10,000 ft, I saw two Me.109Es diving towards the bombers and after the first E/A had had a wing shot away by a Blenheim, the second pulled up and I followed him. I was able to fire 3 short bursts from my cannons and M/Gs from astern at 150-200ydsand the Me.109 rolled down emitting black smoke. The pilot was seen to bale out but the aircraft went down out of sight. I fired 26 rounds from each of 2 cannons and 100 rounds from each of 4 M/Gs.”

On the 3rd July, the Squadron took part in two sorties over France. In the second, ten Spitfires took part, 7 from “A” Flight and 3 from “B” Flight of which P8522 piloted by Flt Lt Jankiewicz was one, taking off at 10:30Hrs and returning at 12:55Hrs as part of Circus 30 escorting Blenheim bombers from No 139 Sqn attacking Hazebrouck marshalling yards.

The following day (4th July), was a heavy day for 303 Squadron with uneventful operation trips, convoy patrols, night flying practice and a variety of aircraft tests. P/O Marciniak took P8522 on a Sector Recon sortie in the late morning followed by an operational sortie for bomber escort duties just before midnight with Sgt Belc at the controls.

It was similar on the 5th when Plt Off Daszewski took P8522 on a training flight (practice formation flying) in the morning with Flt Lt Zak taking P8522 on an uneventful patrol after lunch.

Zak again took P8522 the following morning when they were tasked with providing top cover for three Stirling bombers attacking Le Trait shipyards. Several more uneventful bomber escort mission were undertaken by P8522 on the 10th & 11th July.

On the 12th July, the Squadron was once again involved in escort duties over France and was involved in a few minor skirmished with the enemy. It is thought that Flt Lt Zak flew P8522 in the afternoon of the 12th on bomber escort duties but cannot be confirmed due to the illegibility of the ORB records.

The 12th of July was the last operation flight of the squadron before leaving Northolt for Speke in Liverpool. There are no more records of P8522 flying with 303 (Polish) Squadron after the 12th July.

After five months of operations, No. 303 Sqn was rested on 13th July moving to Speke near Liverpool, in 9 Group, Fighter Command.

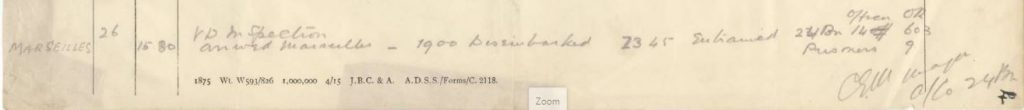

According to the aircraft transfer record card, P8522 Melton Mowbray & District was transferred on the 15th September to No 65(East India) Sqn at RAF Kirton Lindsey. It is thought that P8522 was allocated to “A” Flight with the code ‘YT-D’ to replace K9907 YT-D which had been shot down a few months previous..

No 65 Squadron was in the process of re-equipping with the MkIIb Spitfires and as a result, was involved in quite a lot of training flights. It was on the 18th September when Sgt Grantham took P8522 YT-D on an “Air Firing” sortie. The ORB entry for the day states “1 section of three aircraft proceeded to North Coates from where a convoy patrol was carried out without incident. 2 sections of 2 aircraft proceeded to Sutton Bridge for air firing (canon testing) on re-equipment of squadron with Spitfires Mark IIb. There was also 1 dusk patrol of 5 aircraft. Practice flights were carried out during the day.”

The 19th was a “nothing of interest to report” day for 65 Sqn and the only aircraft to fly was P8522 YT-D at the hands of P/O Mitchell who took ‘D’ for a training flight calling at Digby, Wittering, Colley Weston and back to Kirton.

The next day was another day of training with 2 aircraft from “A” Flight and all aircraft from “B” Flight proceeded to Manby for air firing due to testing of canons on re-equipping to MkIIb Spitfires. That day, Sgt Chandler was the first to take ‘D’ off to Manby and back on an air firing sortie, leaving Kirton at 11:55Hrs. Sgt Oldnall did the same in the afternoon departing at 14:30Hrs.

P/O Mitchell was back in control of P8522 when on the 22nd; the Squadron left Kirton for Detling, about 3 miles NE of Maidstone in Kent to take part in an offensive sweep. The aircraft returned to Kirton in the afternoon on the account of “unfavourable weather conditions”. P/O Mitchell and P8522 were one of two aircraft tasked later that day in taking part in an operation sortie from Kirton, the other being F/Lt Grant and P8576.

65(East India) Squadron were next involved on operation flying on the 24th, with 2 sections of 2 aircraft undertaking operation patrols but this didn’t include P8522. However, Sgt Chalmers did get airborne in YT-D when he was tasked with a local practice flight involving formation flying. Sgt Warden did the same on P8522’s next trip on the 26th September when they were tasked with formation flying again.

Sgt Chalmers took P8522 up twice on the 1st October and again on the 2nd taking part in Army Co-Operation “Bumper” Exercises at RAF Oulton in Norfolk. He returned to Kirton on the 3rd.

Bumper exercises were undertaken in East Anglia during October and November 1941 to test the ability of British forces to destroy a German Army after invading Great Britain. Two Army Headquarters and four Corps participated. The total number of divisions taking part was twelve; three of these were armoured. Two army tank brigades and corps troops in large numbers were also involved. The force engaged amounted in all to about a quarter of a million men.

65 (East India) Squadron must have done a good job on the Bumper exercise as the post exercise report stated ” Air Support. On the air aspect, the C.-in-C. mentioned the following

points. (A) Don’t use your air support ” in penny packets. (B) The fighter appears to present a serious menace to troops and transport on the move. (C) The Air Support Control should be at Army HQ if this is as far forward as it ought to be. It does not follow, however, that it should not be sent to some lower formation’s HQ if the main weight of air support is being directed to this formation’s area.” To read the full report, click here.

The 4th October saw P/O Hewlett getting airborne first in P8522 on a weather test followed later in the day by P/O Mitchell taking P8522 to North Coates for Shipping patrol duties.

It wasn’t long before P8522 was re-allocated again, when on the 6th October 41 she went to 616 (South Yorkshire) Sqn due to 65 Sqn converting to the Spitfire MkV.

616 were currently at RAF Westhampnett, near Chichester in West Sussex and the Squadron ROB states: “We heard today, with mixed feelings, that we were to move up to Kirton Lindsey on the sixth to replace 65 Squadron. It will be remembered that at the end of February we came down to Tangmere to take the place of 65 Squadron after a stay of over 5 months at Kirton Lindsey. The reason why our feelings are mixed is because we shall be sorry to miss all the operational activity, which only No 11 Group Stations can offer, although naturally this decreases as the long nights set in. Also, when we go to No 12 Group, we find that the squadron has to do many more duties for the Station, making it sometimes difficult to obtain a sufficient number of men to service the aircraft. On the other hand Kirton is nearer to most of the homes of the airmen and the accommodation is better than down South.”

The ORB entry for the 6th Oct states “The main party travel up to Kirton. The pilots could not fly up owing to rain and low clouds. Four New Zealand Sergeant pilots join the Squadron, i.e. H. A. Chandler, G.L.Davidson, J.H.Davidson and G.H.Lattimer. They were with 65 Squadron and as they were not trained they were transferred to us. Sgt Pilot A.H. Gunn (Rhodesia) posted to us from 56 O.T.U Grangemouth.

The 7th goes on to state “As weather was still bad the pilots came up by train. Once again we are bitterly disappointed with the dirty conditions of the aircraft, dispersal huts and billets which we took over from 65 Squadron. (see entry of February 26th 1941). Even the ammunition and canon barrels were rusty. The engineer officer insisted on the Squadron being made non-operational for at least 10 days in order to overhaul the aircraft (old Spitfire IIBs). 136 Squadron (Spitfire IIB) and 121 Squadron (the second Eagle Squadron) Hurricane IIBs are at Kirton.”

It would appear that 616 Squadron moved to Kirton Lindsey on or around the 6th October leaving their Spitfire MkVs at Westhampnett and re-equipped with the older MkIIs inherited from 65 (East India) Squadron, who moved South to Westhampnett on the 7th and re-equipped with the newer MkV version, possibly those left behind by 616 Squadron.

P8522 was transferred from 616 to 611 (West Lancashire) Squadron who were based at RAF Drem, East Lothian Scotland. 611 Sqn had been based at RAF Hornchurch carrying out offensive sweeps over occupied northern France since January 1941, but had moved North to RAF Drem for ‘rest’ in November 1941 where they stayed until June ‘42.

The first sorties with 611 Sqn took place on the 5th December 1941 when Flt Sgt Wright took her on a couple of shipping convoy patrols, the first at 08:15Hrs and returned at 09:30Hrs closely followed by another patrol at 10:25Hrs till 11:25Hrs.

On the 8th December, a dull and windy day by all account, two Spitfires from 611 Sqn were sent to Patrol Burnt Island in Fife. Flt Sgt Wright took P8522 and Sgt Johnstone in P7385.

The Squadron was tasked with operating out of Montrose for 3 days from the 12th December and 6 aircraft from B Flight proceed up to Montrose in the early afternoon. The Melton Spitfire however remained at Drem and at 17:00Hrs was on patrol over Eyemouth with Sqn Ldr Watkins in control.

Only 2 aircraft flew on the 15th from Drem, Flt Sgt Wright in P8522 and Sgt Haggas in P8468 were patrolling St Abbs Head. It was a bright day with high winds and bitterly cold. The Squadron was visited by 10 press reporters from various parts of Lancashire. the pilots ‘put on a good show’ and the visitors who were wined and dined by the Sqn left in a contented state of mind.

More patrols were undertaken by Flt Sgt Wright in the Melton Spitfire on the 16th December and then the aircraft didn’t fly again until the 28th when Sqn Ldr Watkins took her on a convoy patrol.

At lunch time on the 14th February, the Melton Mowbray Spitfire was 1 of 4 aircraft involved in a lunch time ‘scramble’ when the alarm bells sounded as an enemy aircraft (later identified as a Heinkel He111) approached the camp, flying at 30,000feet. The Spitfires gave chase but could not get within firing range before the enemy aircraft was lost in cloud.

P8522 flew twice the following day with Sgt Johnson at the controls. The first on a patrol around May Isle then at 11:30Hrs she was scrambled with Sgt Johnson again at the controls along with W3628 piloted by Flt Lt Winskill. Sgt Jones was at the controls when again she was scrambled on the 16th to intercept enemy aircraft approaching.

On 21st February 1942 P8522 was involved in an accident and was transferred to Scottish Aviation at Prestwick where the Melton Spitfire was ‘Repaired In Works’ on the 26th Feb and on the 7th March it was re-classified as a ‘Repaired Aircraft Awaiting Allocation’.

On the 13th March 1942, P8522 was transferred to No 37 MU at RAF Burtonwood in Cheshire. The role of 37MU was to receive brand new aircraft direct from the manufacturers and prepare them for squadron service and to incorporate all the latest modifications and armaments. The aircraft were then put into storage to be issued to the squadron as and when needed. 37 MU also operated an Aircraft Repair depot (ARD) repairing aircraft that had been battled damaged, or had crashed etc. P8522 remained at RAF Burtonwood until 21st April 1942.

The next unit to operate P8522 was No 1 Coastal Artillery Co-operation Flight (CACF) located at RAF Detling, 3 miles North East of Maidstone in Kent. On 1st January, 1942, No.1 Coast Artillery Co-operation Flight became No.1 Coast Artillery Co-operation Unit, and transferred from No.70 Group to No.35 Wing Army Co-operation Command.

Within a couple of weeks of arriving on No 1 CACU, the Melton Spitfire was involved in another incident when Fg Off H L D Tanner made a heavy landing at RAF Weston Zoyland putting the aircraft out of action until the 15th May 42 when she returned to her home base at RAF Detling following repair.

Early in 1942 the Unit took part in various exercises with the Army and Royal Navy. A number of practice shoots were carried out with 540 and 520 Coast Regiments at Dover, but no operational flying was requested during the first four months of this year. Operational sorties were carried out from May onwards, mainly reconnaissance of shipping and targets for the long range guns. A number of “Rhubarbs” were successfully carried out during the Autumn of 1942.

On 16 July, Plt Off P F Sewell 47422 was flying P8522 on a non-operational (local flying) sortie when it was involved in an accident on landing. Due to the amount of damage sustained, the aircraft was categorized as Flying Accident Category B (FACB). A Cat B accident is classed as beyond repair on site by station personnel but personnel from No 88MU were drafted in to carry out the repair which started on the 20th July 1942 and was completed with the aircraft being handed back to No 1 CACU on 7th August.

The accident record card states: “Pilot made normal landing and starboard tyre (possibly punctured on take-off) deflated during run. When passing over depression in the ground, the aircraft lurched causing Port u/c to stress at the anchorage and collapse, following which the starboard u/c collapsed. AOC: Pilot not to blame.”

In August 1942, Sqn Ldr D J Hamilton was bringing the Melton Spitfire into land when he made a ‘wheels up’ landing on the airfield. The aircraft was repaired and a month later on the 29th September Hamilton was again flying the Melton Spitfire on a sortie tasked with spotting form the artillery when it collided with birds. On landing, the aircraft was damaged further when it tipped on its nose. Again it was repaired and declared operational on the 2nd October.

On 23rd November, the training Flight returned to Detling with all aircraft and equipment. Towards the end of 1942, night flying practice in Spitfires was carried out with 520 and 540 Coast Regiments at Dover in an effort to ascertain if spotting with Spitfires was feasible at night, but this was found to be impracticable.

P8522 was involved in another accident on the 22nd October when flying over enemy territory France at very low level and collided with birds at 1045hrs. The pilot, Fg Off Robert James Gee managed to get her back home and the damage was classed as Cat AC – repair beyond unit capacity. Again P8522 was repaired on site and was handed back to No 1 CACU on 17th April 1943.

The Melton Spitfire remained No 1 CACU 19th June 1943 when it was re-allotted and taken on strength by the Tactical Air Force.

On the 23rd October 1943 P8522 was transferred to No 61 OTU at RAF Rednal near Shrewsbury to train new pilots for Fighter Command.

It stayed until 11th August 1944 when it was transferred yet again to No 45MU at RAF Kinloss in Scotland where it stayed until it was eventually struck off charge on the 26th April 1945 due to it being deteriorated beyond repair.

The Melton Mowbray & District Spitfire P8522 served the country well being utilised on the front line. As she became superseded by newer advanced versions of the Spitfire, she carried on serving her country in various other roles.

P8522 had been engaged in combat with German bombers and fighters, escorted allied bombers over enemy occupied territory, took part in Rhubarb and Circus Operations, help train the British Army in the Bumper exercises, escorted shipping convoys and carried out patrols to protect the UK from attack, helped train the Coastal Defence units and latterly assisted with training newly qualified fighter command pilots on the Spitfire.

All in a days work for The Melton Mowbray & District Spitfire that was paid for by the generosity of the people of our market town and surrounding villages. We should be proud of our achievement.