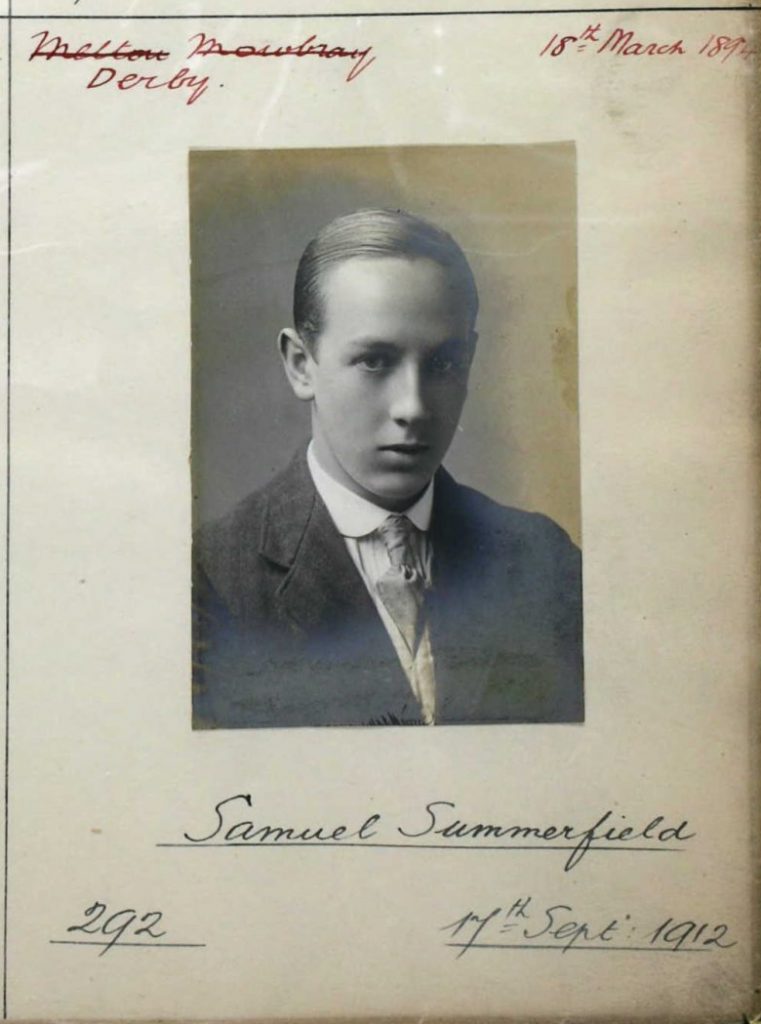

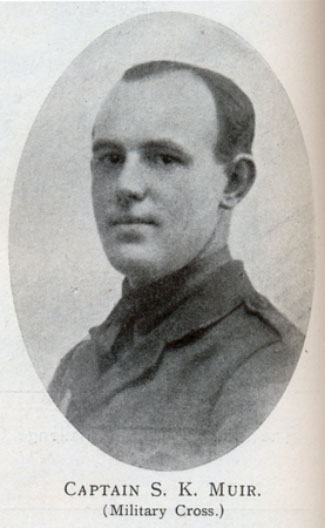

Stanley Keith Muir was the youngest son of parents John Franklin Muir, a Scot by birth who emigrated to Australia in the 1870s & his wife Josephine Muir (nee Holmes). He was born on 6th April 1892 at Elsternwick in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and had 4 elder sisters and two elder brothers.

From the age of six, he was educated at Scotch College and later at the Church of England Grammar school in Melbourne from 1907. Whilst at the Grammar school, he was diagnosed with an illness which turned into hip disease resulting in him leaving the school.

After a period of six months laid up on his back, plus another six months on crutches, followed by a lengthy break at Gulpha (Gulpa) Station he eventually made a full recovery. At Gulpha station there were several houses and stock loading facilities at the rail siding.

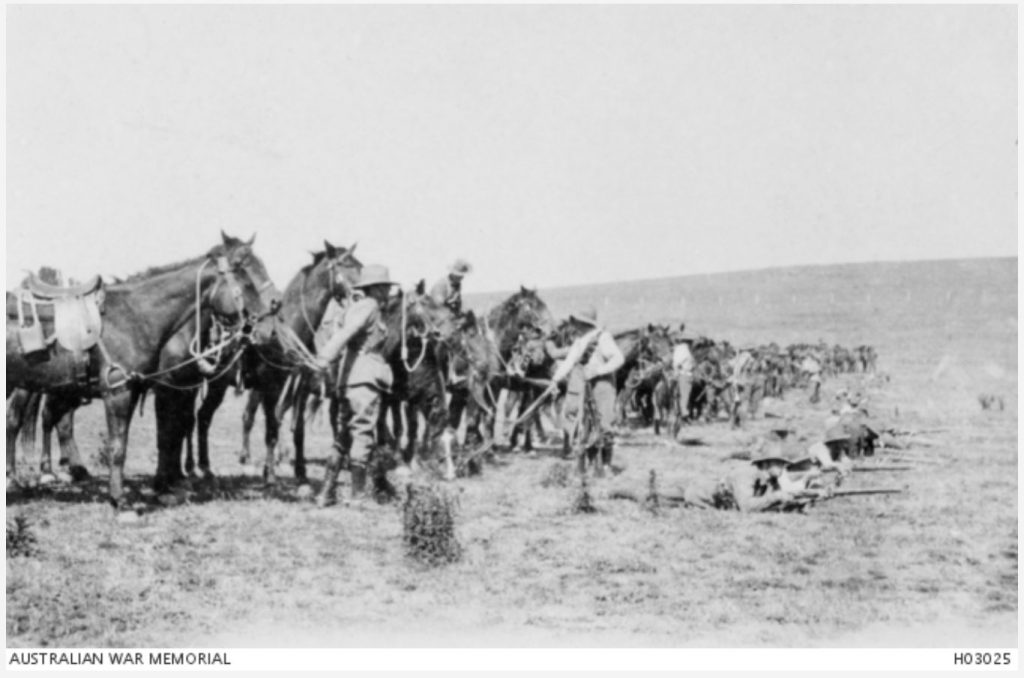

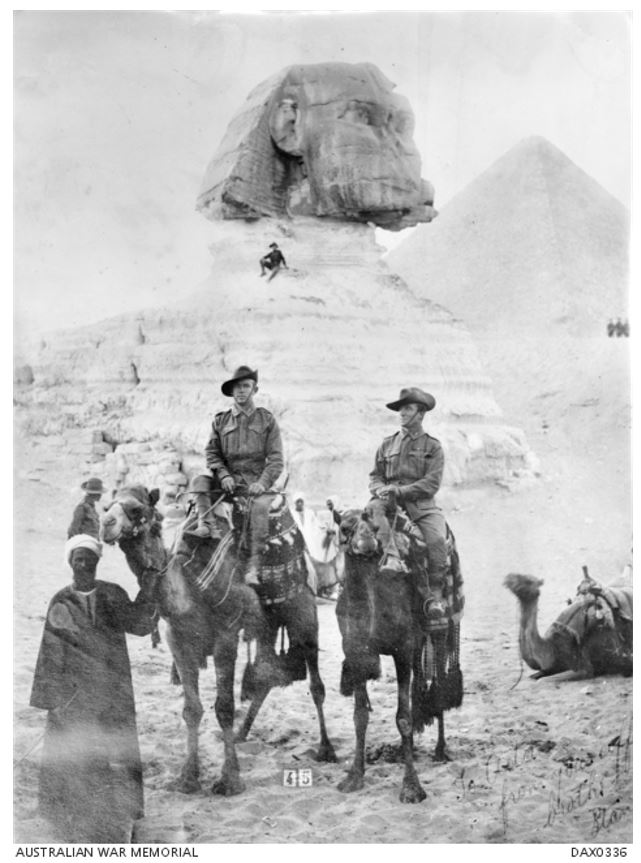

Stanley, or Stan as he was known, joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 18th August, 1914. He enlisted with the 4th Light Horse Regiment (LHR) which had just been formed at Broadmeadows Camp Melbourne only a week earlier.

Light horse regiments were normally comprised of twenty-five officers and 497 other ranks serving in three squadrons, each of six troops. Stan was assigned to “A” Squadron and allocated service number 152 with the rank of Private.

According to his enlistment papers, he was aged 22 and gave his occupation as a Station Overseer. As an overseer he would have been an excellent horseman, skilled as a stockman with sheep, whip and droving. On his enlistment papers he also stated that he had served with the 29th Light Horse.

The Light Horse were mounted troops with characteristics of both cavalry and mounted infantry, who served in the Second Boer War. Prior to the First World War, the 29th Light Horse were known as Port Philip Horse or Victorian Mounted Rifles and were part of the Citizen Military Force/Militia part time forces.

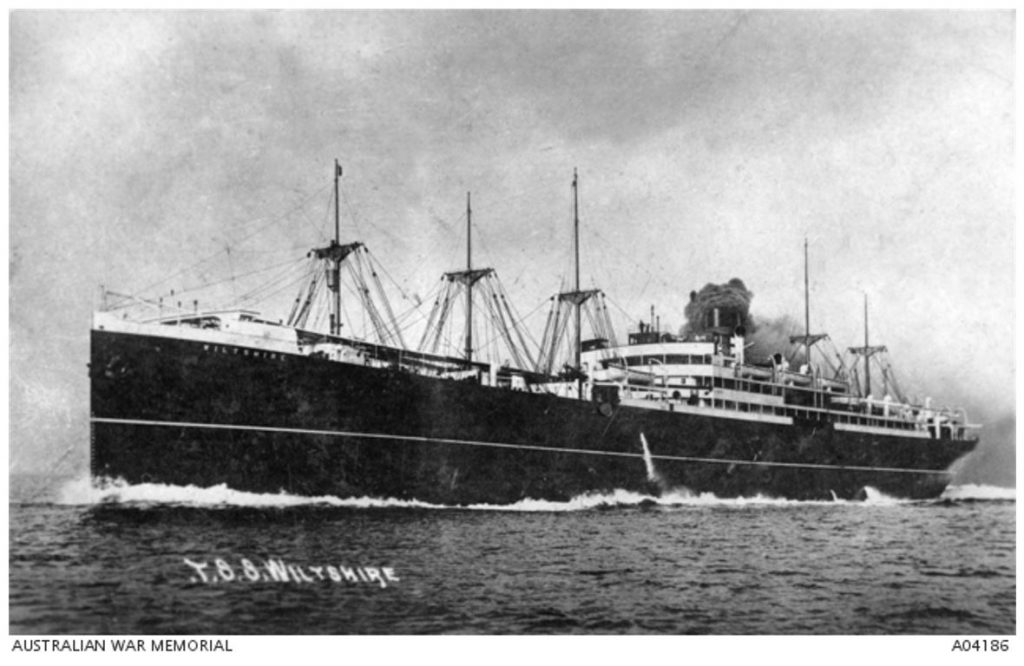

Following the completion of his training at Broadmeadows camp, Stan and his pals from the 4th LHR embarked at Melbourne and sailed aboard the troopship HMAT A18 Wiltshire bound for Egypt where they arrived on the 10th December 1914.

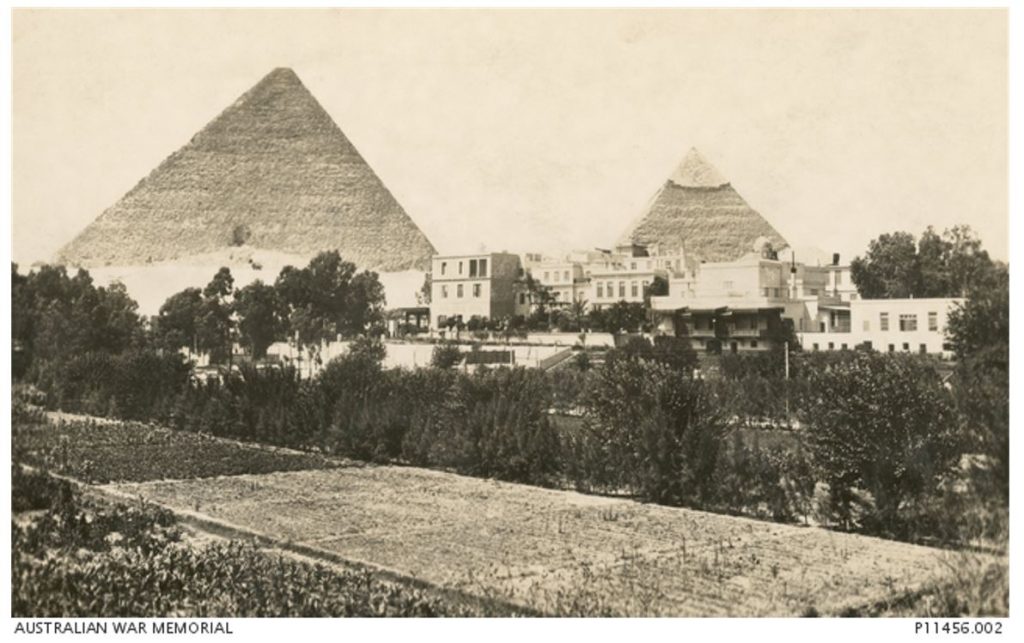

Once in Egypt, the LHR were based at the Mena training camp at Cairo to undertake training prior to going to France.

When the rest of the division departed Egypt to take part in the Gallipoli campaign, the LHR were left behind as the authorities believed that mounted troops would not be needed in the campaign due to the terrain. However, infantry casualties were so severe it was decided to send them as infantry reinforcements without their horses. Whilst still in Egypt, Stan was taken ill on the 24th March 1915 suffering with Subacute Rheumatism and as a result he was admitted to the No 2 Australian General Hospital based in the Mena House Hotel at Cairo.

After staying at the Mena hospital for about a month, he was transferred to the convalescent hospital at Abbasia on the 25th April. Whilst at Abbasia, the 4th LHR left Egypt for Gallipoli, landing at ANZAC Cove between the 22nd & 24th May. On arrival, the regiment was broken up and provided squadrons as reinforcements for infantry battalions at various points around the beachhead, and it was not until 11th June that the regiment concentrated as a formed unit.

Following his convalescence break at Abbasiya, Stan rejoined to his Unit at ANZAC Cove as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) on 27thJuly, 1915.

On the 13th August, whilst at Gallipoli, Stan was promoted to Corporal. According to the book “War Services Old Melburnians” Stan was wounded during the Battle of Lone Pine which took place between the 6th and 10th August but there is no evidence of this in his service records. I wonder if it was due to his actions during the battle that he earnt the promotion.

However, just a few weeks later, he was taken sick on the 28th August with Rheumatic fever and transferred to the Hospital Ship Ascanius. On the 31st he was transferred to the St Andrews Military Hospital in Valetta Malta arriving on the 2nd September 1915.

After a two week stay in the St Andrews Hospital, Stan was transferred to the hospital ship Carisbrooke Castle on the 17th September for onward transfer to England.

On his arrival in England, Stan was admitted to the Fulham military hospital on the 24th September with Enteric Fever. A few days later he was transferred from Fulham to the Addington Palace hospital on the 28th, from which he was discharged for furlo (leave) on the 30th.

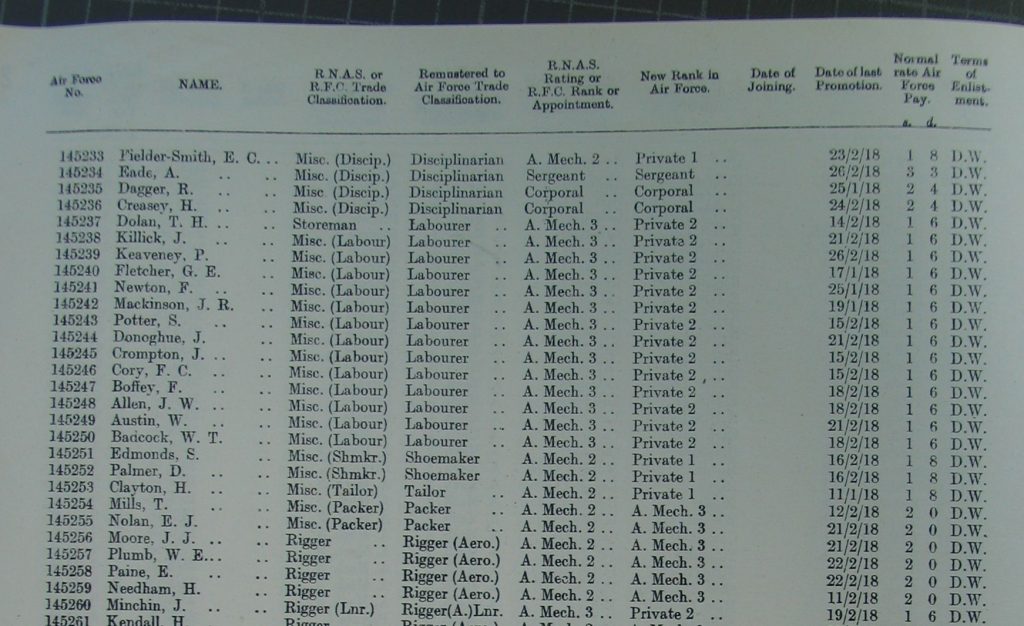

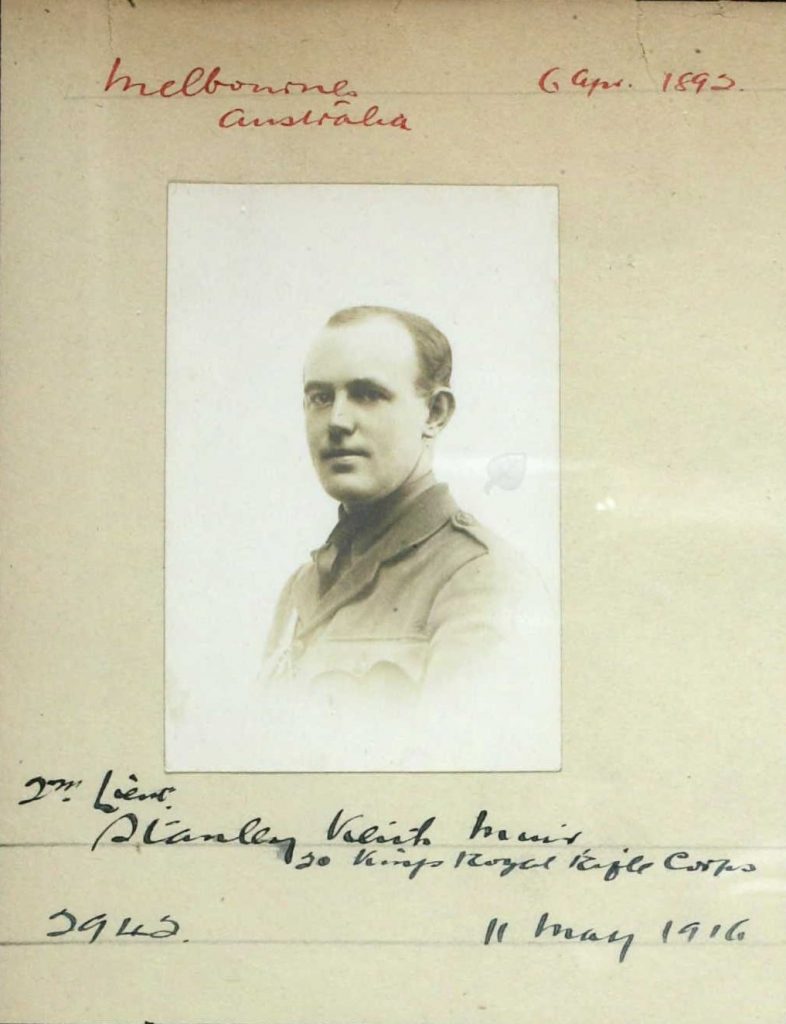

Whilst undergoing convalescence in England, Stan thought he would be re-assigned back to garrison duties. Being an ambitious type, this did not meet expectations and on the advice of friends, he applied for a commission. On the 16th November, he was discharged from the AIF due to being appointed a commission in the 20th Service Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps (British Empire League Pioneers). He was assigned as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant at Norfolk House, Laurence Pountney Hill, London.

After a short course at an Officers School in Cambridge, he joined his unit, the 20th Bn KRRC in London. By the middle of February the battalions strength stood at over 1,000 and Colonel Murray suggested to the War Office about moving outside of London in order to access better training facilities.

The 20th Bn KRRC were a new unit formed in London on the 20th August 1915 by the BEL. The BEL helped to mobilise troops during the Second Boer War and the First World War and was active in the dominions of Australia and Canada during the early part of the 20th Century.

In response, the War Office asked Lieut-General Wooley Dodd to inspect the battalion and to see if they were ready to go out to France. this took place in Hyde Park on the 18th February. As the unit had only just received its full complement of men and no training was given, especially in arms drill or musketry due to being no rifle range in London. Wooley Dodd advised the War Office that they should be moved to a training camp.

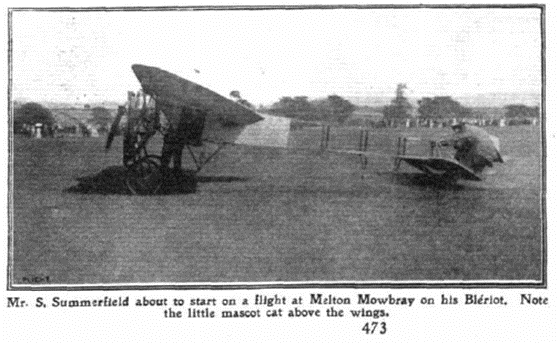

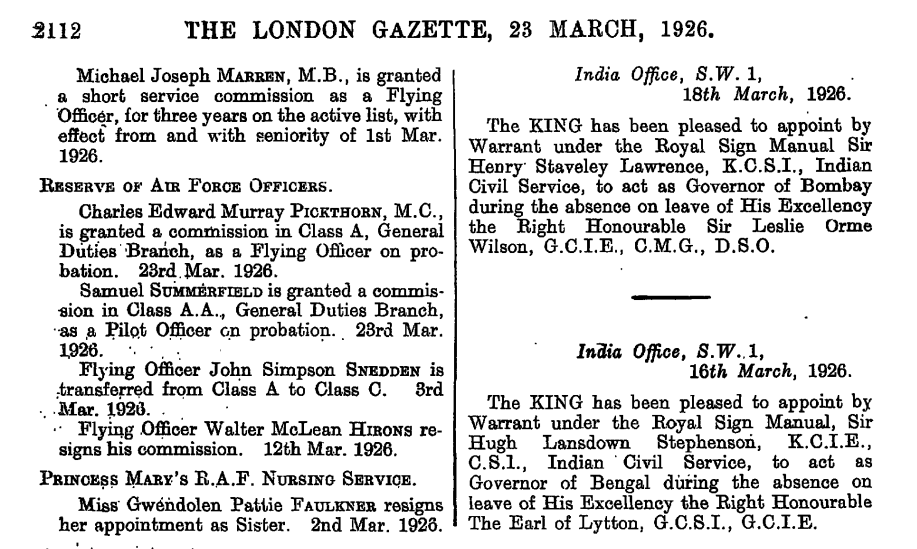

Stan wasn’t with the 20th Bn KRRC for that long as whilst based in London, near to the Hendon aerodrome, he had a strong desire to become an aviator. Contrary to the advice of his superior officers in the KRRC, he applied for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps which was granted in March 1916.

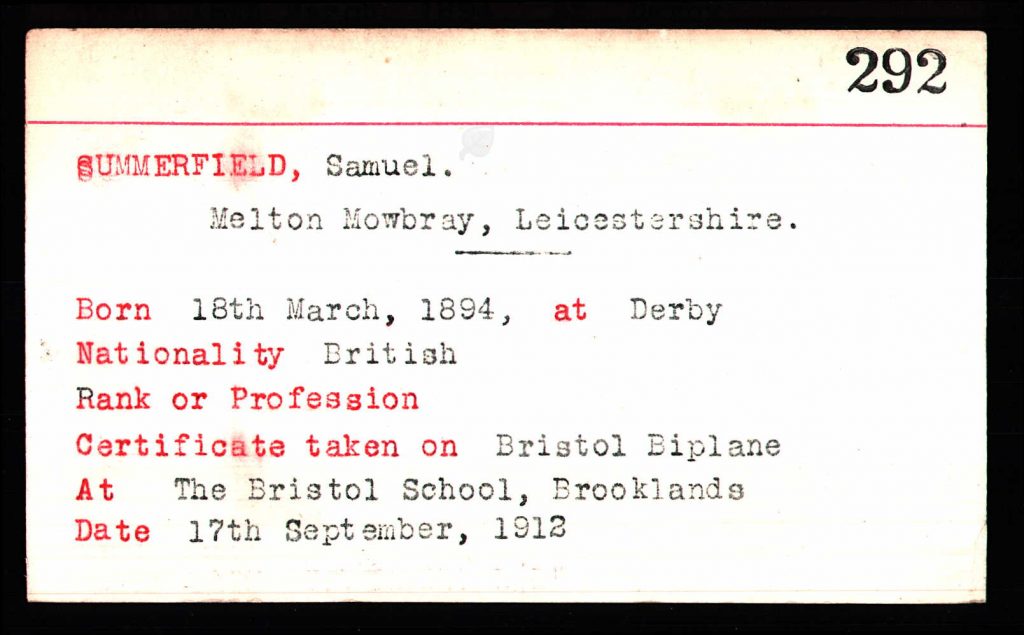

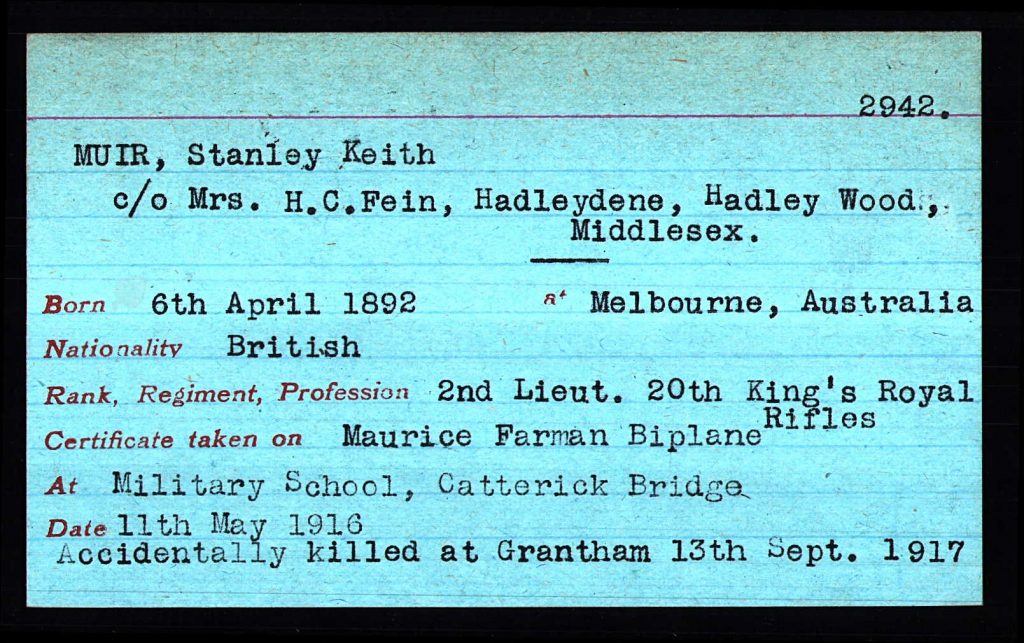

He was at the Military School at Catterick Bridge where he passed all his examinations with credit and earned his pilots’ wings on a Maurice Farman Biplane, being awarded the Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate No 2942 on the 11th May 1916.

As a newly qualified pilot, Stans next assignment was to No 1 (Australian) Squadron on the 27th July 1916 who were based at Heliopolis in Egypt as an instructor. The Sqn was declared operational at its new headquarters in Heliopolis on 12th June, when it took over aircraft belonging to No.17 Sqn RFC. According to his service records, whilst in Egypt, Stan was temporary attached to No 17 Sqn RFC at Kaulara en-route for Salonika.

From 12th September 1916, the British began to refer to No.1 Squadron as No.67 (Australian) Squadron RFC. His service records confirm he returned to his unit (67th Sqn on the 27th September.

Whilst serving with No. 67(Australian) Sqn he was admitted to hospital on the 18th October for treatment at the No 26 Casualty Clearing Station. His records do not say why he was admitted, but he was discharged back to his unit the following day.

Stan and his fellow members of No 1 Sqn were involved in the Sinai campaign in 1916. As a result of his actions during December, he was awarded the Military Cross. The following entry appeared in the London Gazette published on the 6th March 1917: “Temp, 2nd Lt. (temp. Lt.) Stanley Keith Muir, Gen List & RFC. For conspicuous gallantry in action. He carried out a daring bombing raid and was largely instrumental in shooting down aa hostile machine. On another occasion he pursued two enemy machines and succeeded in bringing one of them down.”

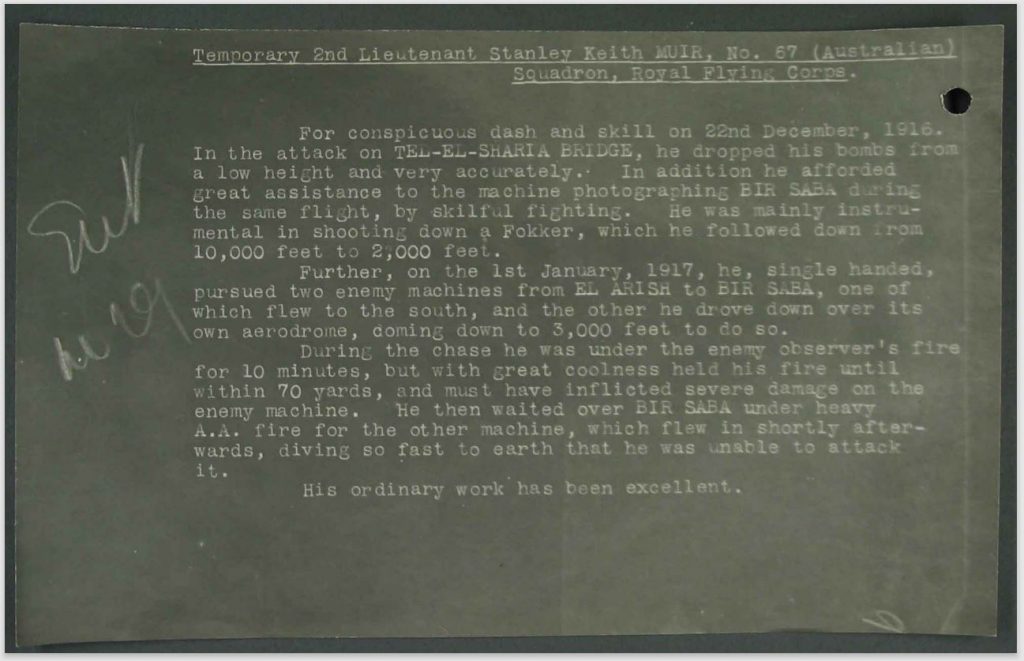

The recommendation for award held by the Australian War Memorial archive goes into more detail “Temporary 2nd Lieutenant Stanley Keith Muir, No. 67 (Australian) Squadron, Royal Flying Corps. For conspicuous dash and skill on 22nd December 1916. In the attack of TEL-EL-SHARIA BRIDGE, he dropped his bombs from a low height and very accurately. In addition he afforded great assistance to the machine photographing BIR SABA during the same flight, by skilful fighting. He was mainly instrumental in shooting down a Fokker, which he followed down from 10,000 feet to 2,000 feet. Further, on the 1st January, 1917, he, single handed, pursued two enemy machines from EL ARISH to BIR SABA, one of which flew to the south, and the other he drove down over its own aerodrome, coming down to 3,000 feet to do so. During the chase he was under the enemy observer’s fire for 10 minutes, but with great coolness held his fire until within 70 yards, and must have inflicted severe damage on the enemy machine. He then waited over BIR SABA under heavy A.A. fire for the other machine, which flew in shortly afterwards, diving so fast to earth that he was unable to attack it. His ordinary work has been excellent.”

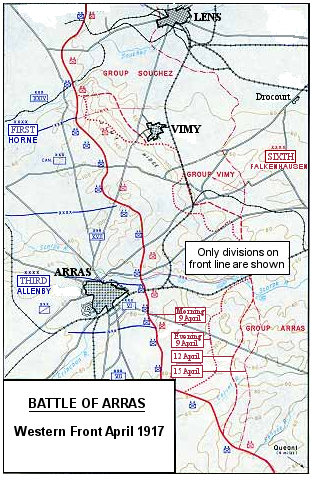

Stan and his colleagues on No 1 Squadron were involved in the third and final battle to complete the recapture of the Sinai Peninsula on the 9th January 1917 which became known as the Battle of Rafa otherwise known as the Action of Rafa.

The weather cleared on 5th January, allowing No 1 Squadron to carry our a patrol where they observed 2 – 3,000 Ottoman soldiers digging defences south of Rafa in the area of El Magruntein.

Two days later, British air patrols found Ottoman garrisons in strength at El Kossaima and Hafir el Auja in central northern Sinai, which could threaten the right flank of the advancing EEF or reinforce Rafa.

While the British air patrols were absent on 7 January, German airmen took advantage of the growing concentration of EEF formations and supply dumps, bombing El Arish during the morning and evening. The next day No. 1 Squadron were carrying patrols all day, covering preparations for the attack on Rafa.

On the 13th January 1917, Stan left the Middle East and embarked aboard the H.T. Kingstonian due to being assigned to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and disembarked at Southampton on the 30th January 1917.

According to records, the Fokker that he shot down was the first victory for the Squadron.

An entry dated 19th January 1917 in his service records show that he was ‘struck off strength 5th Wing’ which No 67 Sqn was part of due to having joined 68 Aust Sqn RFC.

The Shepparton Advertiser newspaper published in Victoria on 14th May 1917 stated that Stan had been promoted to Flight Commander and Captain. “Capt. Stanley Muir (brother of Mr C. R. Muir, Euroa), has been promoted to the rank of Flight-Commander in the Royal Flying Corps, Egypt. Captain Muir, who is only 24 years of age, has been twice mentioned in Sir Douglas Haig’s despatches, and has been awarded the Military Cross.”

The next entry on his service records was by OC 68 Sqn on the 26th August 1917 stating that Captain Muir had marched in to No. 68 Squadron at Harlaxton, from Overseas with effect from 18th August, 1917.

The village of Harlaxton lies 12 miles North East of Melton Mowbray and 2 miles South West of Grantham, just across the border into Lincolnshire. The airfield itself was located in a triangle of flat fields midway between Harlaxton Manor (now the University of Evansville’s British campus) and the nearby village of Stroxton.

The airfields that were chosen were not always ideal as OC 24th Wing stated in his memo to HQ Training Brigade dated 10 Jan 1917. ‘Ref. yr. secret TB/809 dated 3/1/17’. “ I was up at Harlaxton yesterday and of the opinion that the aerodrome is not fit to be classed as a Night Landing Aerodrome until the tree stumps on the aerodrome have been removed. Urgent application has been made to the contractors to do this.”

No 68 Sqn were based at Harlaxton until September 1917 when they deployed to France.

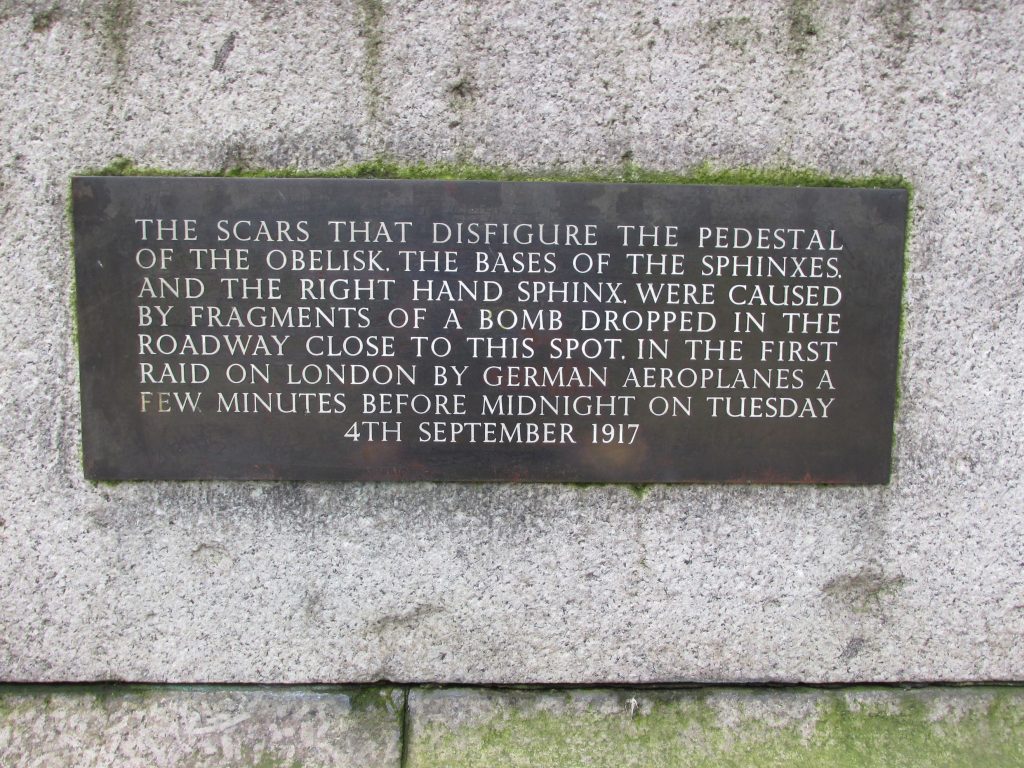

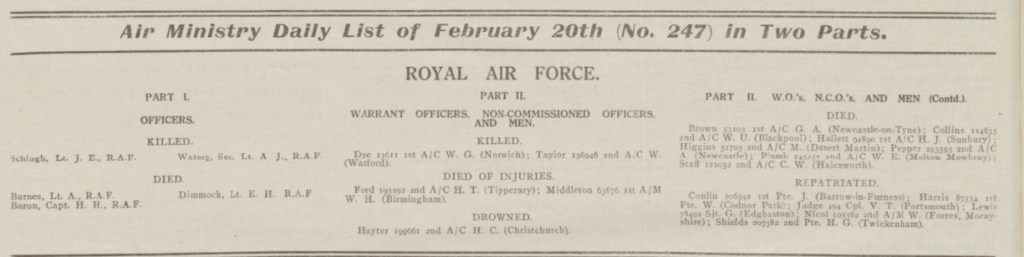

It was during the build up for France that tragedy struck the Squadron. The following entry is from the War Diary of No 2 Sqn for the month of September 1917.

“On September 12th, just before the squadron left England it suffered a terrible loss in the death of Capt. Muir (M.C.) as the result of an accident whilst flying a D.H.5. He was buried at Harlaxton Cemetery with full military Honours and Lieut. G. C. Wilson (D.C.M.) was appointed to command “B” Flight in his stead. The squadron finally mobilised 16.9.17 and Lieut Tooth in charge of Squadron Transport left Harlaxton on that date, the remainder of the personnel leaving by rail on the 21st…”

Stan is buried in the churchyard of SS Mary and Paul at Harlaxton. His grave is marked by a CWGC Commission headstone which bears the inscription “BELOVED SON OF JOHN AND JOSEPHINE MUIR MELBOURNE IN LOVING MEMORY”

Stans old Grammar School published an obituary for him in their Old Melburnians 1918” Stanley Keith Muir who was killed in England on 12th September 1917 as the result of an aeroplane accident was the son of Mr J. F. Muir. He was born in 1894 and was at the School in 1907 but left owing to illness, which eventually developed into hip disease. He as for six months on his back and another six months on crutches, but gradually grew out of his trouble, and after a long sojourn on Gulpha Station in Riverina was completely cured. He was a well-known amateur rider at picnic races in the Deniliquin district, and was a very fine horseman. He enlisted in the 4th Light Horse, was all through the Gallipoli campaign (though illness kept him back from the Landing), was wounded at Lone Pine and invalided to England. He was there given a commission in the King’s Royal Rifles, but soon transferred ti the Royal Flying Corps, and obtaining his wings in May 1916 was sent to Egypt to instruct an Australian flying squadron. He carried out single-handed the great Baghdad railway flight. He flew 600 miles without a stop in 6 ¼ hours, and bombed the railway line, and was highly commended for work at Et Arish. He was attacked by three German aeroplanes. He brought down one and pursued the others over the Dead Sea till his petrol gave out. For these feats he was awarded the Military Cross. He returned to England and was about to leave for the West front when the fatal accident occurred. He had been in the air for about twenty minutes, and was about to take his swoop for hanger when one of the wings snapped and he fell 500 feet and was killed instantly. He was regarded as one of the six best flyers in the British Army and was noted for his “stunts.” A comrade writing of him says: “Our crowd were all broken up over his death, for he was white to the soles of his feet.” Major Oswald Watt, writing to his father, says: “His sad death deprives the flying service of one they can ill afford to lose. Never was an officer more truly mourned by his fellow-officers or by his men.”

In 2017, whilst on a visit to the UK, personnel from No 2 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force paid their respects at his grave. Air Combat Officer Flt Lt Joseph Noble said for a unit with a long and proud history as 2 Sqn “the opportunity to visit its roots was not to be missed”. He went on to say, “One can imagine the impact of his death would have had on the other men of the squadron”.