I have been interested in war memorials for just short of 40 years now and this stems back to when I was a young cadet of around 13 or 14 years of age with No 967 Kirkham and South Fylde Sqn Air Training Corps.

I can’t remember the exact year, but as I said previously, I must have been around 13 or 14 when I was given the honour of laying a wreath on Remembrance Sunday at my local war memorial at Wesham in Lancashire.

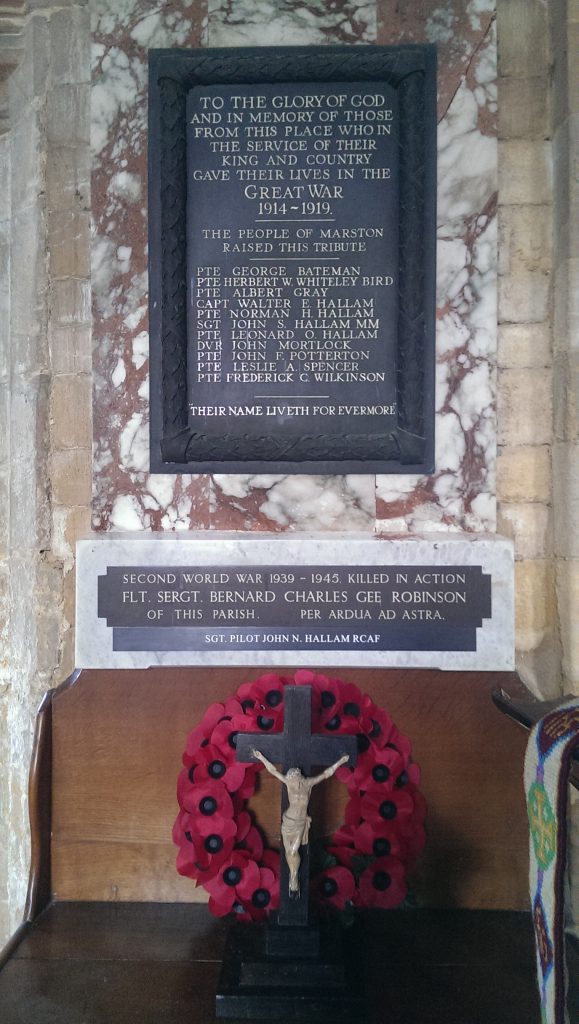

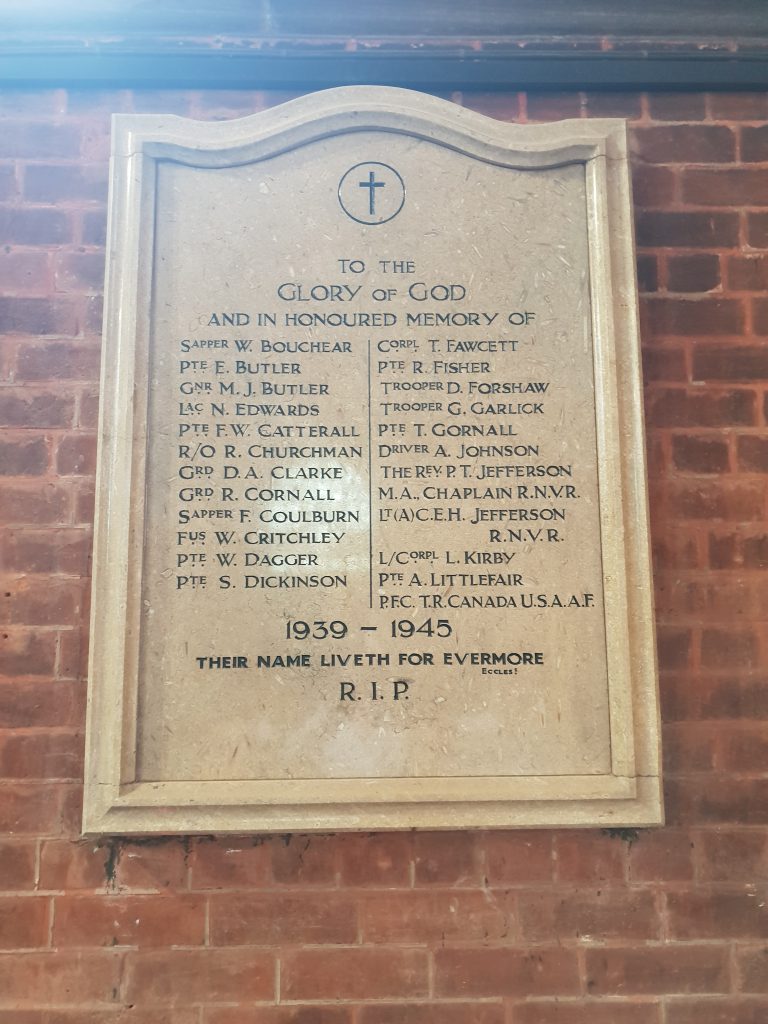

Believe me, it was an honour, as on that memorial is the name of my Uncle, Frank Coulburn, who was a Sapper serving with No 9 Field Company, Royal Engineers during WW2 and he was killed at Dunkirk on 2nd June 1940, last seen on the beach during the evacuation. Sadly, his body has never been recovered, or if it was, never identified and as such he has no known grave.

On what I think was the same year, I was also part of the Guard of Honour at the Kirkham War Memorial, being one of four cadets, one stood on each corner of the memorial during the wreath laying ceremony. The town Mayor and other local dignitaries laid the wreaths whilst us cadets stood there with our heads bowed and our Lee Enfield .303 rifles in the arms reversed position in an act of remembrance, a pose that is quite common with figures of military personnel on war memorials, just like the one at Wesham.

You are all undoubtedly aware of the sayings/speeches that are made at times of Remembrance and these are generally referred to as The Kohima Epitaph and The Exhortation.

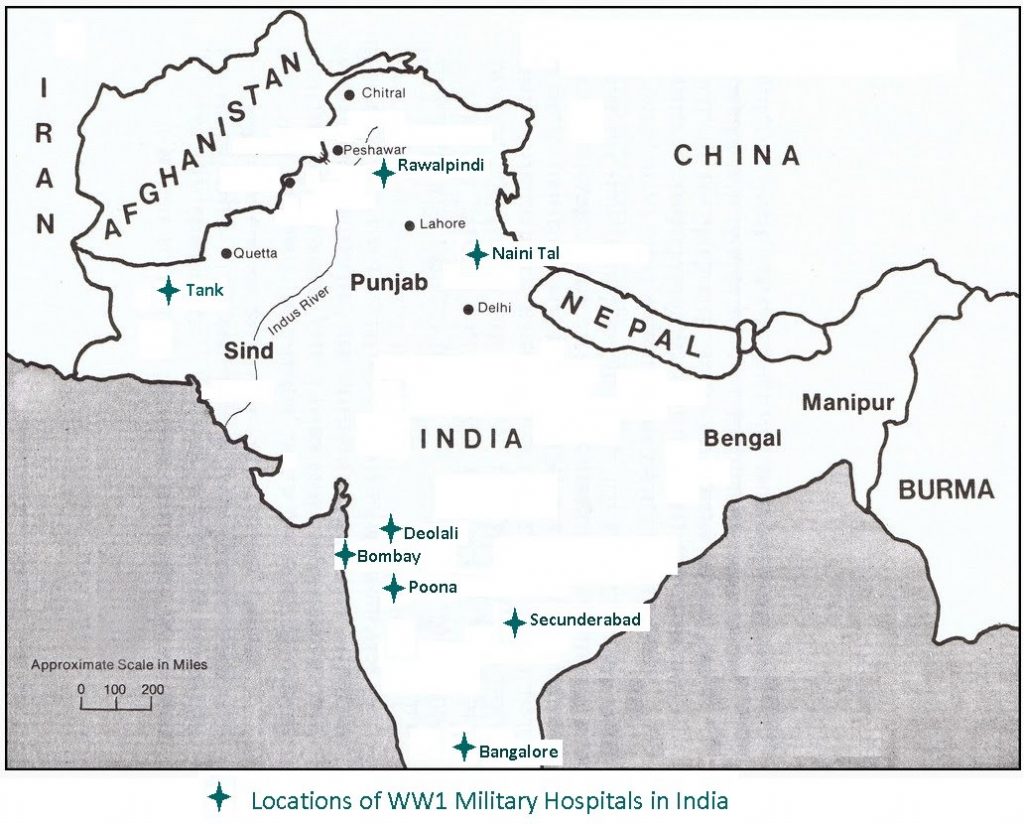

The Kohima Epitaph is the epitaph carved on the Memorial of the 2nd British Division in the cemetery of Kohima (North-East India). It reads:

‘When You Go Home, Tell Them Of Us And Say,

For Your Tomorrow, We Gave Our Today.’

The verse is attributed to John Maxwell Edmonds (1875-1958), and is thought to have been inspired by the epitaph written by Simonides to honour the Greeks who fell at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480BC.

The Exhortation is an extract from a poem written in mid-September 1914, just a few weeks after the outbreak of World War One, by Robert Laurence Binyon called “For the Fallen”.

The Exhortation is read out during Remembrance Ceremonies, immediately after the Last Post is played, and leads into the Two Minute Silence.

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old,

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun, and in the morning,

We will remember them.”

Response: “We will remember them.”

But how do we remember them?

Away from the Remembrance Ceremonies, everyone has their own way of remembering their fallen relatives and one method, especially for the families of those who never returned was, and still is today, via the erection of war memorials.

What is a war memorial though?

A war memorial can be any tangible object which has been erected or dedicated to commemorate war, conflict, victory or peace. They can also commemorate casualties who served in, were affected by or killed as a result of war, conflict or peacekeeping; or those who died as a result of accident or disease whilst engaged in military service. This can also include civilian casualties and not just service personnel.

War memorials can come in many different shapes and sizes, such as:

Sculpted figures, crosses, obelisks, cenotaphs, columns, etc

Boards, plaques and tablets (inside or outside a building)

Roll of Honour or Book of Remembrance

Community halls, hospitals, bus shelters, clock towers, streets etc

Church fittings like bells, pews, lecterns, lighting, windows, altars, screens, candlesticks, etc

Trophies and relics like a preserved gun or the wreckage at an aircraft crash site

Land, including parks, gardens, playing fields and woodland

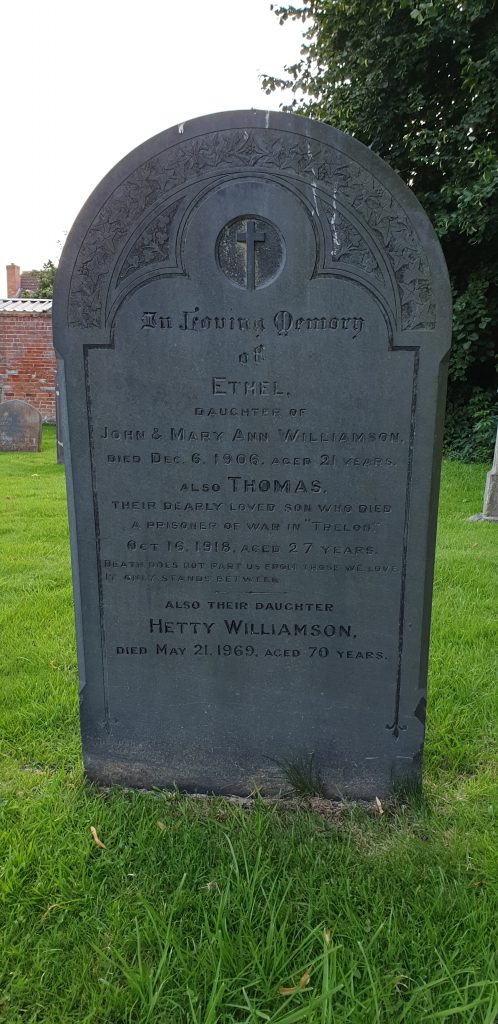

Additions to gravestones (but not graves)

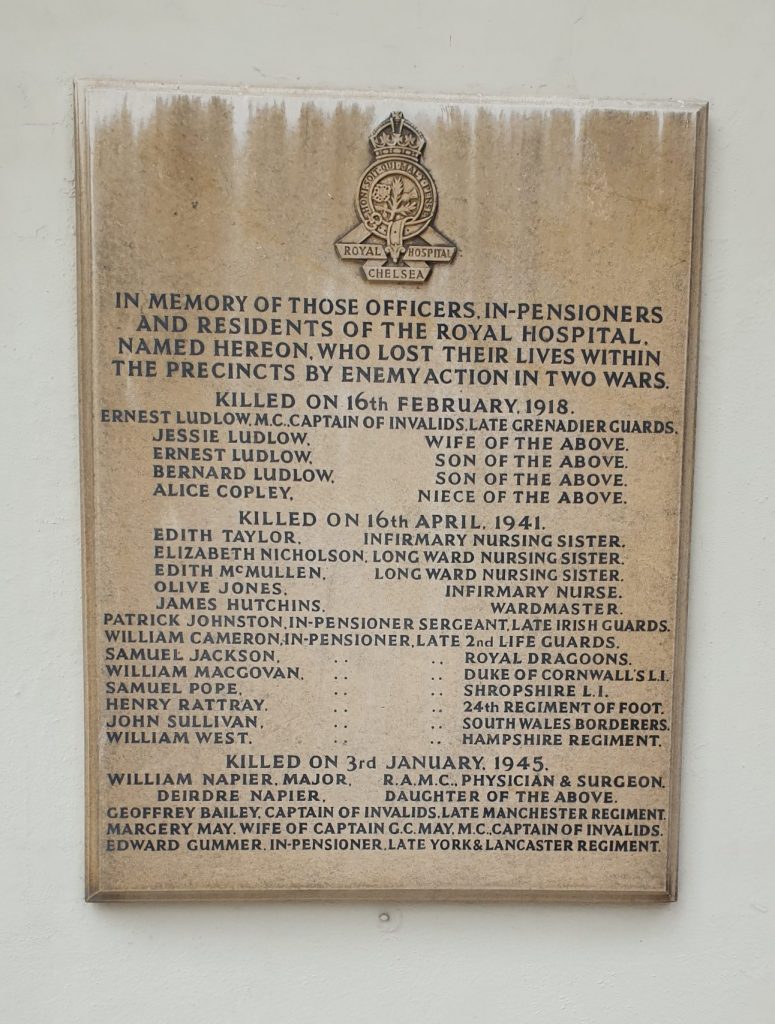

I suppose you could say that one of the first national war memorials in this country was The Royal Hospital at Chelsea. In 1681, responding to the need to look after these soldiers, King Charles II issued a Royal Warrant authorising the building of the Royal Hospital Chelsea to care for those ‘broken by age or war’.

Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to design and erect the building and in 1692 work was finally completed and the first Chelsea Pensioners were admitted in February 1692 and by the end of March the full complement of 476 were in residence.

War memorials can be found in just about every town or village across the country. There are so many First World War memorials in this country that it is easy to stop seeing them. For the majority of people, they just walk past them as if the memorial is so much part of everyday street furniture without even giving it a second glance. Even direct descendants of those named on them don’t pay that much attention to them.

Probably the most iconic war memorial in this country, and the one that most individuals are familiar with is The Cenotaph, located on Whitehall in Central London. It is the countries national memorial to the dead of Britain and the British Empire in the First World War and conflicts that have taken place since and is the focal point of the annual service of remembrance.

The Cenotaph was designed by Sir Edward Lutyens OM, the foremost architect of his day and was responsible for many of the commemorative structures built in the years following World War One by the Imperial War Graves Commission, now known as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Another famous war memorial that people will be aware of, but not necessarily associate it as a war memorial is another of London’s iconic landmarks, Nelsons Column in Trafalgar Square. The monument was constructed between 1840 and 1843 to commemorate Admiral Horatio Nelson, who died at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. It stands, 169 feet 3 inches tall from the bottom of the pedestal base to the top of Nelsons hat.

There are four bronze panels around the pedestal each cast from captured French guns. They depict the Battle of Cape St Vincent (14th February 1797), the Battle of the Nile (1st – 3rd August 1798), the Battle of Copenhagen (2nd April 1801) and the Battle of Trafalgar (21st October 1805), all battles in which Nelson took part in.

Prior to the 1890s, the majority of war memorials across the country only commemorated aristocrats, the rich and famous who became officers of the British Army and Royal Navy.

However, in 1899 and the outbreak of the Second Boer War (1899-1902), regular soldiers were in short supply and volunteers stepped forward into the breach by joining the local volunteers Militia.

Thousands of these so called ‘amateur’ Militia volunteers were killed during the campaign, and those that returned home following the end of the war, were hailed as heroes as they had survived conflicts like the Sieges of Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley.

Consequently, thousands of Boer War memorials were erected up and down the country ranging from brass plaques to large elaborate sculptures in town centers. Whatever their design, they all had the same purpose of commemorating not only those Officers from well to do families but also the ‘common’ soldier that had made the ultimate sacrifice from either being killed in action or dying of illness contracted whilst serving in South Africa.

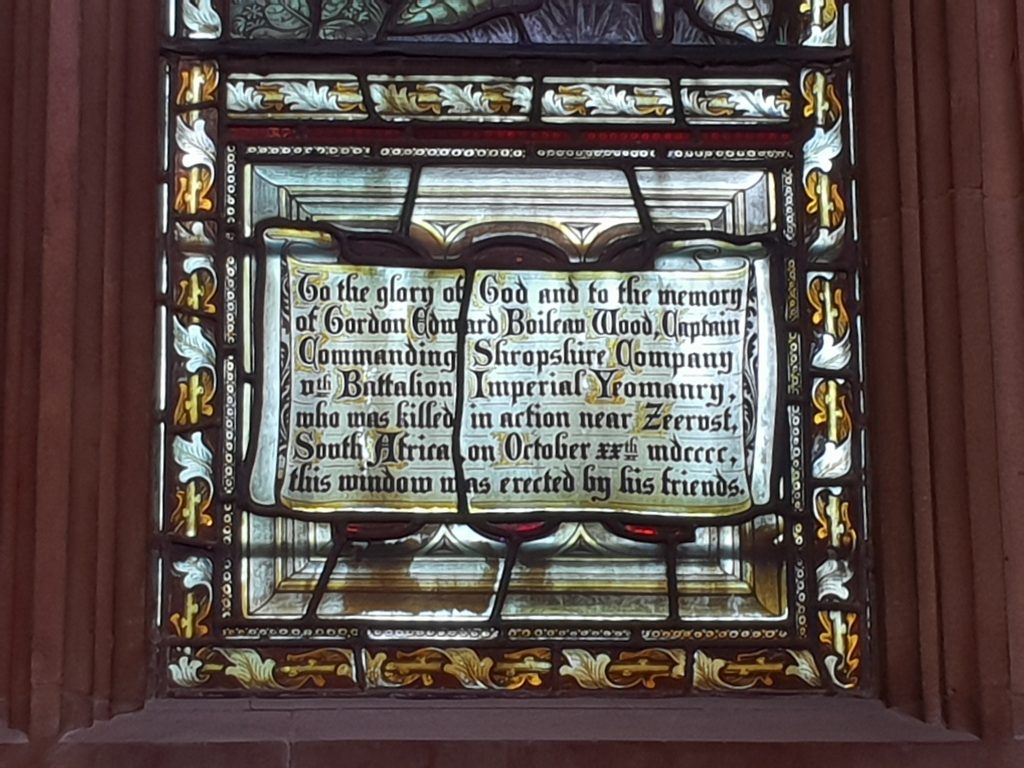

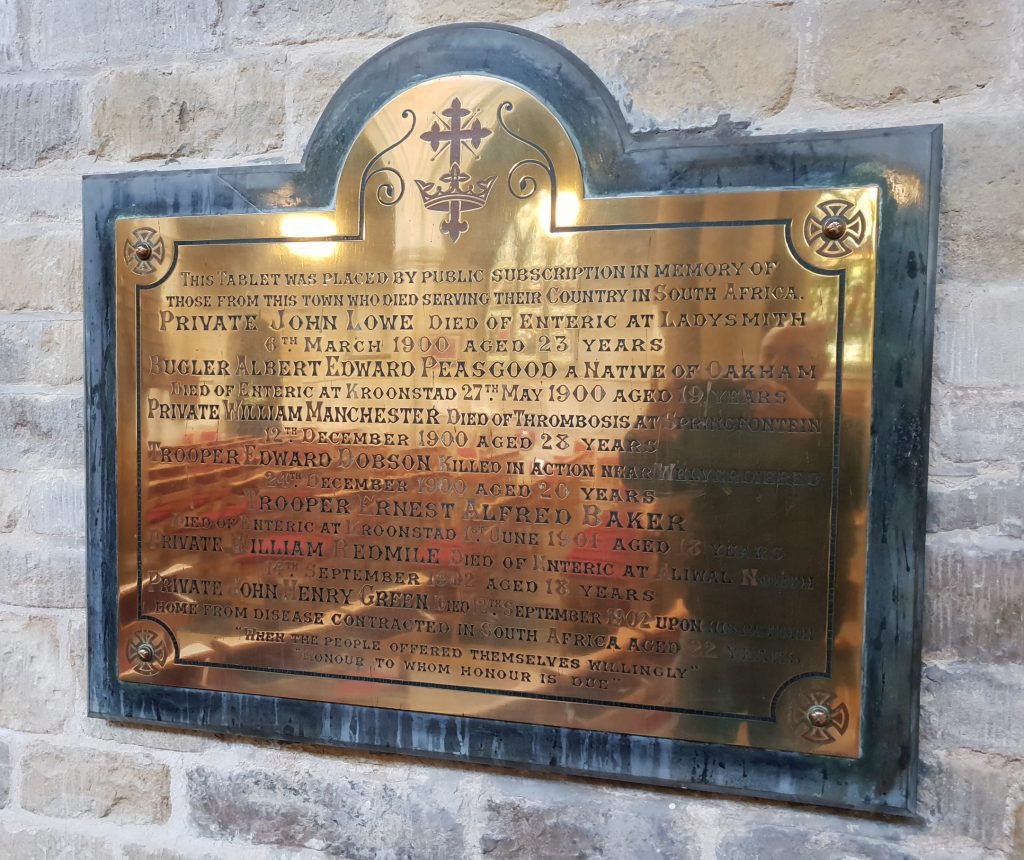

One such example of a Boer War memorial can be found in my local Parish Church of St Mary’s here in the market town of Melton Mowbray where I live.

On Saturday 20th December 1902, The Grantham Journal published the following article in their newspaper:

“Honour to Whom Honour is Due”—The memory of Meltonians who sacrificed their lives in the South African war is to be perpetuated by a splendid brass tablet, suitably inscribed, which is to be placed in the Parish Church, probably the nave. The names of the seven who fell, and which will appear on the tablet, are Privates John Lowe, Wm. Manchester, Wm. Redmile, and John Henry Green, Troopers Edward Dobson and Ernest Alfred Baker, and Bugler Albert Edward Peasgood, of Oakham, a member the Melton Volunteer Corps. The matter is in the hands of Mr. Willcox, who has collected most of the subscriptions for the purpose, a ready response being made in this respect. Work is in the hands of Messrs. J. Wippall and Co., of Exeter and London, and the tablet, which will be of an ornamental character, will be mounted a polished slab of black marble. The Vicar has kindly agreed to forego the fee of ten guineas which is entitled in respect of fixing of the tablet in the Church. It is expected that it will be ready towards the end of the month of February, and it will be unveiled at a special service arranged for the occasion, which will be attended by the local Volunteers and Yeomanry. A special effort is being made among the Volunteers in the matter of subscriptions the fund for memorial, and Sergt. J. Sutherland has undertaken to receive the same.

A special unveiling ceremony for the dedication of the memorial was held on Sunday 15th March 1903.

The brass plaque is described as “Containing a cross with red infill, encircled by a crown within nowy head & a cross at each corner fixing point, all infilled in black. An engraved single-line, inwardly radiused, at each corner, forms a border around inscription area, with a decorative open termination at top centre within nowy head.”

THIS TABLET WAS PLACED BY PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION IN MEMORY OF THOSE FROM THIS TOWN WHO DIED SERVING THEIR COUNTRY IN SOUTH AFRICA

PRIVATE JOHN LOWE DIED OF ENTERIC AT LADYSMITH 6th MARCH 1900 AGED 23 YEARS

BUGLER ALBERT EDWARD PEASGOOD A NATIVE OF OAKHAM DIED OF ENTERIC AT KROONSTAD 27th MAY 1900 AGED 19 YEARS

PRIVATE WILLIAM MANCHESTER DIED OF THROMBOSIS AT SPRINGFONTEIN 12th DECEMBER 1900 AGED 28 YEARS

TROOPER EDWARD DOBSON KILLED IN ACTION NEAR WELVERDIERED 24th DECEMBER 1900 AGED 20 YEARS

TROOPER ERNEST ALFRED BAKER DIED OF ENTERIC AT KROONSTAD 1st JUNE 1901 AGED 18 YEARS

PRIVATE WILLIAM REDMILE DIED OF ENTERIC AT ALIWAL NORTH 14th SEPTEMBER 1902 AGED 18 YEARS

PRIVATE JOHN HENRY GREEN DIED 12th SEPEMBER 1902 UPON HIS RETURN HOME FROM DISEASE CONTRACTED IN SOUTH AFRIVA AGED 22 YEARS

“WHEN THE PEOPLE OFFERED THEMSELVES WILLINGLY”

“HONOUR TO WHOM HONOUR IS DUE”

As part of the unveiling ceremony, a parade of the Melton Mowbray volunteers took place including the Melton and Gaddesby troops of the Leicestershire Imperial Yeomanry, twenty-nine members of the Oakham detachment of “N” Company of the Leicestershire Volunteers, under Sergt. J. C. Kernick and the Church Lads Brigade and a regimental band from Leicester was also in attendance.

A large congregation assembled in the Church and the unveiling ceremony was performed by General Brocklehurst who raised a toast to the King and an appropriate dissertation was also read by the vicar, Rev R Blakeney.

After the unveiling, the Last Post, and the anthem ‘Blest are the departed’ by Spohr was sung by the choir.

Another example of a Boer War memorial is that which can be found in the Town Hall Square Leicester on the corner of Every Street & Horsefair Street. This memorial takes on a different for to the plaque in St Mary’s and is a low granite wall with bronze plaques containing the names of 315 of Leicestershire’s men who died in the war. It is made up of a central squat pedestal with bronze kneeling angel in flowing robes holding sword and olive branch, showing Peace. Figures of grief & war are also mounted on the end pillars.

During my travels across the UK, and even overseas, when I come across a war memorial, I will always pay it a visit, read the inscription and take photographs of it. There are plenty of the memorials that are lovingly cared for and maintained by local authorities and communities. Sadly though, this is not always the case as it was slowly dawning on me that a lot of these memorials were either neglected or suffering from effects such as weathering, pollution, and in some cases vandalism.

Coming across quite a few memorials that, shall we say were not in the best of conditions for whatever reason, I decided several years ago to join the War Memorials Trust as a member and also as a Regional Volunteer to ‘do my bit’ and try to ensure that “We will remember them” and the individuals named on the memorial inscriptions are “Not Forgotten.”

Throughout the United Kingdom, there are estimated to be over 100,000war memorials. They were, and still are today, erected by communities and in the majority of cases via public subscription as a means for communities to focus their grief and provide a means of Remembrance because so many who died or are classed as missing were never repatriated or have no known grave.

As I have discovered during my travels, many memorials are treasured, maintained and cared for with maintenance plans in place, but others are sadly neglected, vandalised or left to suffer the effects of ageing and weathering.

This is where the War Memorials Trust comes in. They want to ensure that each and every memorial is preserved and the memory of the individuals recorded, whether they be from past or present conflict, civilian or service personnel, remembered.

Who are the War Memorials Trust?

Back in 1997 an ex-Royal Marine, by the name of Ian Davidson, went to one of the Committee Rooms at the House of Commons to report on the ‘scandal’ of Britain’s war memorials.

Ian Davidson shocked those in attendance with his report that although the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was doing a magnificent job caring for the graves and memorials to our war dead abroad (post 1914), no one – and no organization – took responsibility for the care of Britain’s war memorials at home, estimated to number more than 50,000 at the time.

As a fall out from this meeting, a new organisation known originally as Friends of War Memorials was formed, changing its name to War Memorials Trust in January 2005.

The War Memorials Trust works with communities, supporting them to provide care for their war memorials which remain a shared ongoing tribute and responsibility. They encourage best conservation practice giving the greatest chance of preserving the original war memorials as they were seen by those who lost loved ones. As current custodians we are acting today not just for ourselves but for those who went before, and will come after, us.

As a charity War Memorials Trust provides advice, offers grants and works with others to achieve its objectives. But it needs help as it relies entirely on voluntary donations to enable it to protect and conserve war memorials in the UK. Gifts, subscriptions, grants and in-kind contributions all assist the charity to achieve its aims and objectives.

The war memorial in the village of Great Dalby near Melton Mowbray commemorates 11 men of the village who died in the Great War and it was unveiled on 25 July 1920. In 2006 a project was undertaken on the memorial to restore it to its former glory. The fence surrounding the memorial needed to be repaired to ensure it was safe and the War Memorials Trust contributed £215 towards this work.

Egerton Lodge War Memorial Gardens are part of landscaped gardens surrounding Egerton Lodge, a grade II listed residential home for the elderly in Melton Mowbray.

In 2008, the War Memorials Trust gave a grant of £2,500 towards the restoration of the terrace. This included cleaning the balustrade and re-pointing the structure with lime mortar. Additionally, the tarmac surface of the upper terrace was replaced with stone paving. The York paving slabs had originally been used on the platform of the Great Northern Station on Scalford Road, Melton, until it’s closed in 1953. When the war memorial was restored in 2008/9, it was decided to use the stone labs on the upper terrace as it was deemed appropriate that those who gathered on the terrace to honour the towns fallen heroes would be standing on the same slabs as some of those who did not return may have stood during their embarkation when they went off to war.

The War Memorials Trust also relies on the efforts of volunteer Contributors to report on the condition of war memorials around the country. These volunteers used to be called Regional Volunteers and they looked after the memorials in their County but that volunteering scheme has now ended as more and more members of the public are also contributing.

If you want to get involved in any way, to help protect and conserve our nation’s war memorial heritage, you can join the Trust as a member. Members donate either an annual subscription of £20 or make a one-off payment of £150 for life membership.

Alternatively, you can get involved by volunteering and reporting on the condition of our war memorials. You can do this by registering online with their War Memorials Online website and then submit photos and condition reports of any war memorials you come across.

In addition to the War Memorials Trust, there are other organisations that help look after War Memorials such as the Imperial War Museum who maintain the War Memorials Register.

Another great organisation is Historic England who provide great advice via their series of downloadable publications providing advice and guidance on preserving war memorials. See their website for more information.

If you’re based in Scotland, then the Historic Environment Scotland website provides similar advice for Scottish memorials. See their website for more information.

And for those of you in Wales, the CADW website also provides information relating to Welsh memorails.

If you are responsible for a war memorial that is metal, did you know that you can help protect it witht he uese of smart water should it be stolen. See the In Memoriam 2014 website for further information.

To help clean memorials, there are also several corporate companies that provide cleaning services. For example the War Memorial Conservation Company , the Independent Memorial Inspection or SMB Restoration Ltd are just some examples of comapnies that provide a memorial cleaning service.

I would recommend that before entering into a contract with any commercial company regarding the cleaning of your war memorial, I would visit the websites of the War Memorials Trust or English Heritage or the equivalent for Scotland and Wales and seek their advice in the first instance.

Sadly, some war memorials are in danger of being lost due to the closure of Churches, Chapels, Factories, and Schools with some building being demolished or others closed or converted into domestic accomodation.

Not always will any war memorials be preserved and unfortunately, some end up being destroyed, dumped in skips or even sold to the scrap man!

Luckily, local organisations such as the Leicester City, County & Rutland At Risk War Memorials Project exist to preserve the war memorials and their aim is “to keep them safe” by taking those at risk into their custody, but wherever possible they try and relocate the memorial to another location within the community from where it came.

For more information about their work, please visit their website here.

If you have any questioins about war memorials, please don’t hesitate to send a message using the email address: email: meltonhistoryfare@gmail.com and I will try and help you or signpost onto a suitable organisation.