“Courageous Duty Done In Love, He Serves His Pilot Now Above”, is the personal inscription or epitaph, written on the Commonwealth War Grave headstone of Victoria Cross recipient Flight Sergeant John Hannah, who is buried at Birstall St James the Great Churchyard in Leicester. What is Courageous Duty?

John, although a V.C. winner, is so typical of many veterans that I have come across in my career with the Royal Air Force and also in my time as a welfare caseworker with the Royal Air Forces Association, the charity that supports the RAF Family.

Many service personnel are too proud to ask for help and try and resolve their issues via their own means, sadly at times, only asking for help when it is too late. John was a prime example.

Being a shy and reserved character, John was not a fan of all the publicity he was receiving following his award of the V.C. and disliked having to go on tours giving public speeches.

In this blog, I try and tell the story of John, not only for his heroic deeds when he showed ‘valour in the presence of the enemy’ which earned him the V.C., but also his bravery and courage in fighting his life debilitating illness and the courage he showed in overcoming his shyness in giving talks to provide a means of income to support his family. I also look at his widow and three daughters and how they showed bravery and courage to fight through their daily struggles following his death.

John Hannah was born on 27th November 1921 in Paisley, Glasgow, to his parents, James a dock crane foreman with the Clyde Navigation Trust and his wife. John was educated at Bankhead Elementary School and Victoria Drive Secondary School in Glasgow, and he was also a member of the 237th Glasgow (Knightswood Church) Boys’ Brigade Company and played football for the local team. After leaving school he took up employment as a salesman in a local boot company.

He has an elder brother James, aged 25 who served in the Green Howards. There was also a younger brother Charlie, who described John as having a reserved disposition.

On the 15th August 1939, just 3 weeks before Britain declares war on Germany, John aged only 17 enlists in the Royal Air Force on a 6 year engagement. Following completion of his initial training at RAF Cardington, he was posted on the 14th September 1939 to the No 2 Electrical and Wireless Training School at RAF Yatesbury to train as a wireless operator.

John and his fellow students would have attended classes from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. six days a week to learn the theory of wireless and how to maintain and operate various types of wireless sets including the Marconi R1155 receiver and the T1154 transmitter.

They were instructed in morse code and how to transmit and receive messages. A competitive system was set up between the students where they would strive to achieve a standard of six words per minute in the sending and receiving of morse code.

After meeting the criteria of six words per minute, they moved on to another table that demanded eight words per minute and worked their way up to the required standard of twelve words per minute. In addition to learning about wireless transmitters and morse, the students were also taught the use of the Aldis signalling lamp for visual communication in morse code.

Once his ground training was completed, John would have then undertaken aerial training as part of his wireless course. The aerial training would have consisted of a series of air experience flights in De Havilland Dominie aircraft operated by the “Yatesbury Wireless Flight”, piloted by civilian employees of the Bristol Aircraft Company. During the air experience flights, John would have been introduced to radio receiver training consisting of sending and receiving messages from base and practicing the art of transmitter tuning by calibration and back tuning to the transmitter.

After completing his training at Yatesbury, John was next posted to the No 4 Bombing and Gunnery School at RAF West Freugh for a short course in air gunnery. After successfully finishing his course in air gunnery, he was next assigned to No 16 Operational Training Unit at RAF Upper Heyford on 18th May 1940 for the final part of his training before qualifying as a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner (WOp/AG).

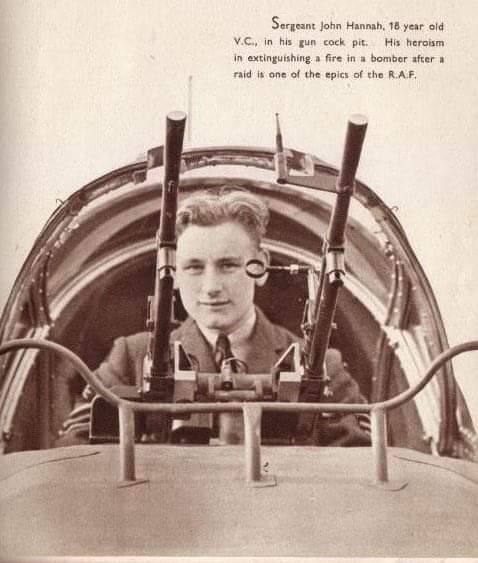

After successfully completing his WOp/AG training, he was promoted to Sergeant and posted on the 1st July 1940 to his first front line unit as what is known as a “Rooki”, serving with 106 Squadron at RAF Thornaby in Yorkshire who operated Handley Page Hampden bombers.

John didn’t serve on 106 Sqn for long as on the 11th August he was posted to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire to join 83 Sqn who again operated the Hampden bomber.

83 Sqn was one of the few Bomber Command units that went into action on the first day of the Second World War by carrying out a bomber sweep over the North Sea searching for German warships. The Sqn continued with daylight ‘precision’ raids against German naval and coastal targets throughout 39/40, but as the daylight operations became more costly, they switched to night operations.

The summer of 1940 has become famous in RAF history for the actions during the Battle of Britain where RAF Fighter Command pilots became known as “The Few”.

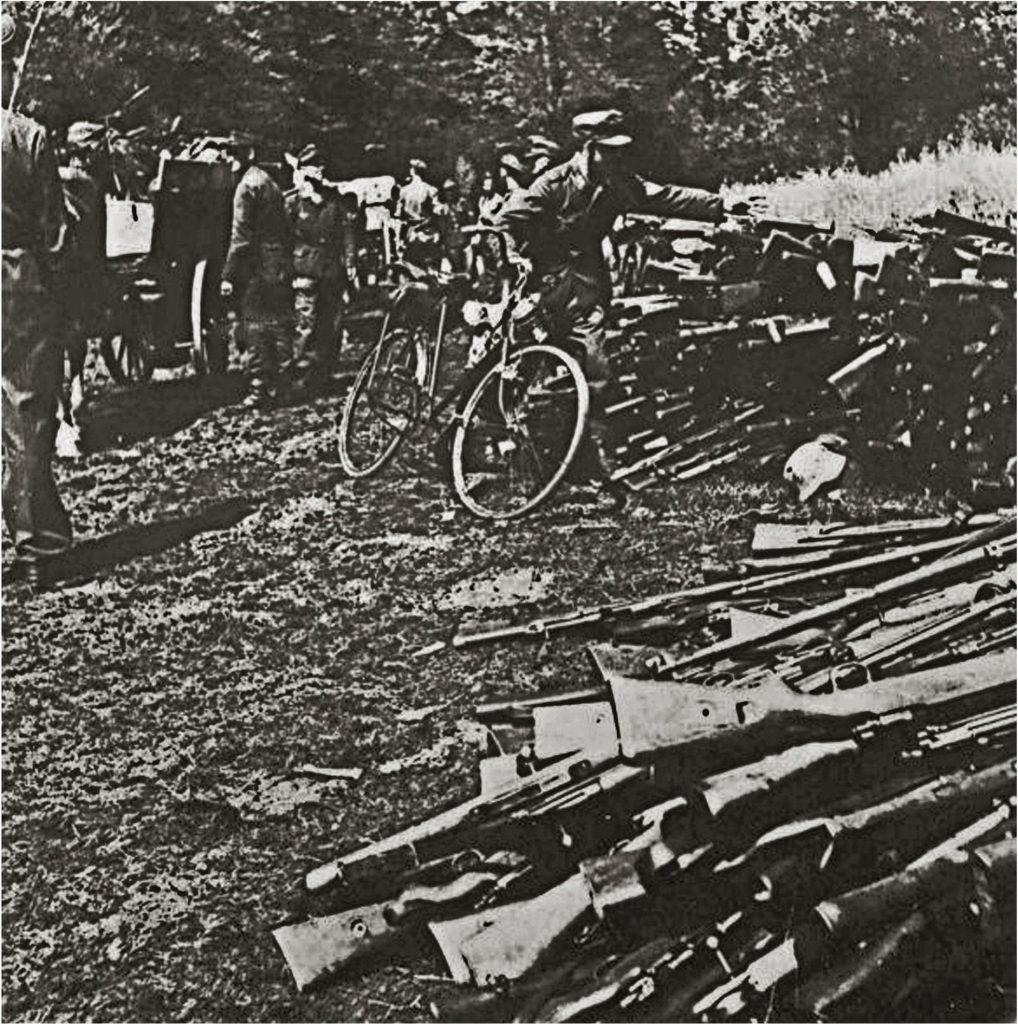

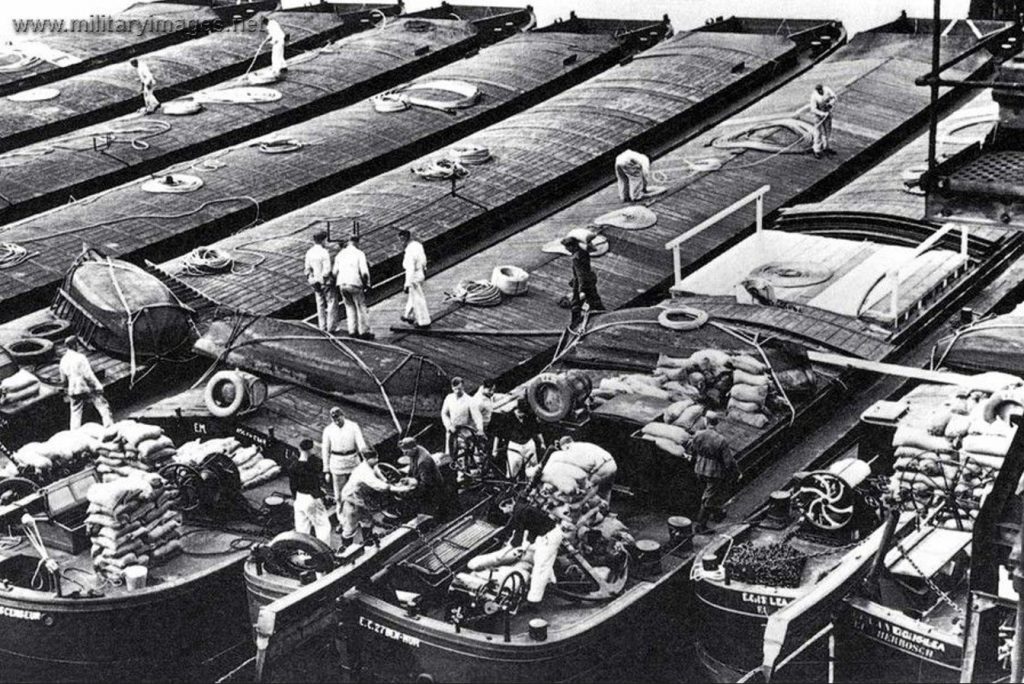

Whilst Fighter Command were heavily engaged in defending the skies above Britain intercepting the German Luftwaffe, Bomber Command units were sent out night after night to attack the naval forces that Hitler was amassing as part of his preparations for the seaborne invasion of Britain known as Operation Sea Lion.

Huge numbers of barges had been observed making their way down the River Rhine as well as other European rivers to congregate in the Channel ports like Antwerp. No 83 Sqn had been flying against concentrations of invasion shipping in the Channel Ports and Germany during the late summer and autumn of 1940.

On Sunday 15th September 1940, the Luftwaffe launched its largest and most concentrated attack against London in the hope of drawing out the RAF into a battle of annihilation in order to destroy its airpower before Operation Sea Lion could be commenced. Around 1,500 aircraft took part in the air battles which lasted until dusk. The action was the climax of the Battle of Britain with the RAF Fighter Command defeating the German raids and the day is now known as Battle of Britain day.

During the daylight hours on the 15th, Bomber Command dispatched 12 Blenheim bombers on sea and coastal sweeps, but all bombing sorties were abandoned due to ‘too-clear’ weather.

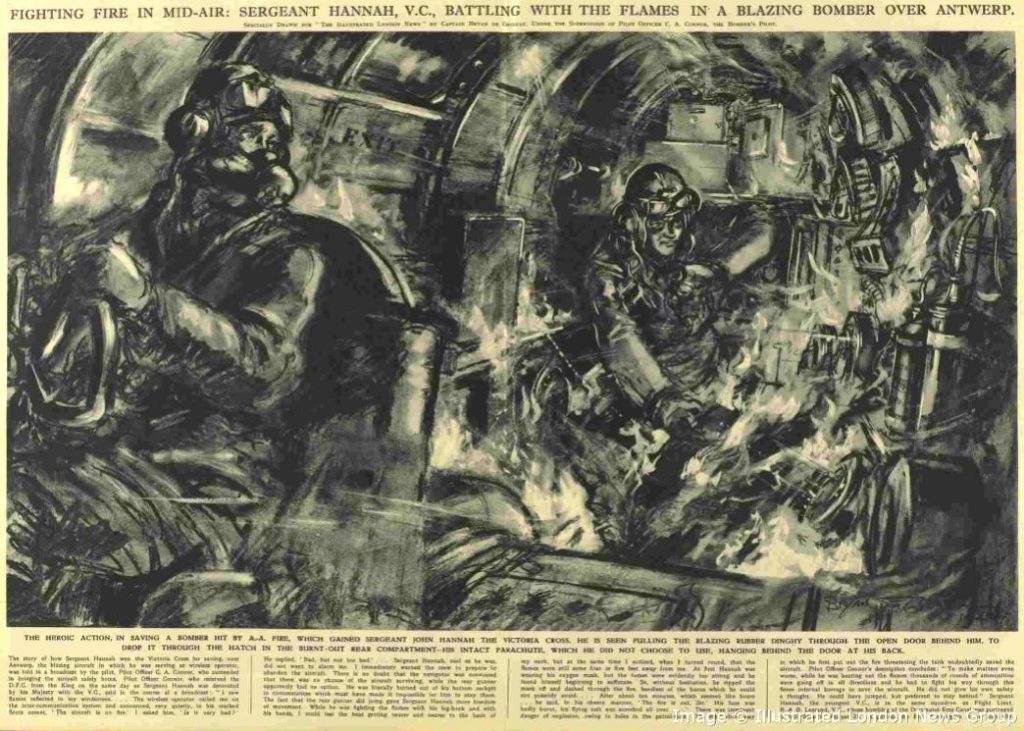

Bomber Command were in action again during the night of the 15th/16th September with 155 aircraft taking part in operations against Channel ports and various targets in Germany against the barges and naval forces Hitler was amassing. No 83 Sqn dispatched 15 Hampdens as part of this force to attack target “Z11” at Antwerp.

All 15 of 83 Sqn’s Hampdens were detailed to attack barges in selected basins at target ID Z11. Eight successfully attacked the target, one aircraft attacked Antwerp in error, two aircraft successfully bombed the secondary target at Flushing (CC2), one aircraft had temporary engine trouble and had to jettison its bombs. One aircraft experienced electrical issues which prevented it from releasing its bombs when attacking the target and another returned to base with its bomb load. Another a/c failed to identify either the primary or secondary targets but attacked a ship in Dunkirk roads on its return leg to base.

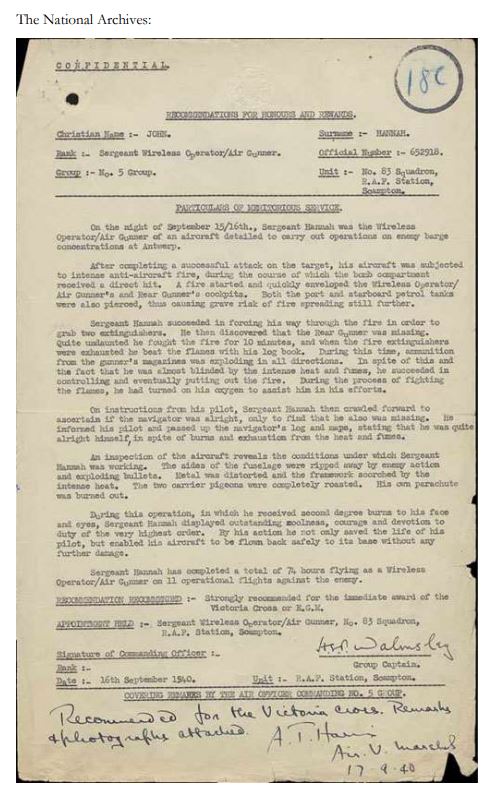

John Hannah took part in this Op as the WOp/AG on Hampden P1355 OL-W. His pilot was Pilot Officer Clare Arthur Connor, with Sergeant Douglas A E Hayhurst as the Navigator and Leading Aircraftman George James as Rear Gunner.

During the first run over the target, the approach was inaccurate, and no bombs were dropped so the pilot went round again. In the second approach at 2,000 feet, the aircraft was subject to intense fire from the ground, but the attack was pressed home successfully. During the attack the bomb compartment was shattered by anti-aircraft fire and the port wing and tail boom were also damaged.

Fire soon broke out in the fuselage, enveloping both the wireless operators and rear gunners’ cockpits. Both port and starboard fuel tanks had been pierced by shrapnel giving risk to the fire spreading. Hannah forced his way through the flames only to discover that the rear gunner had left the aircraft.

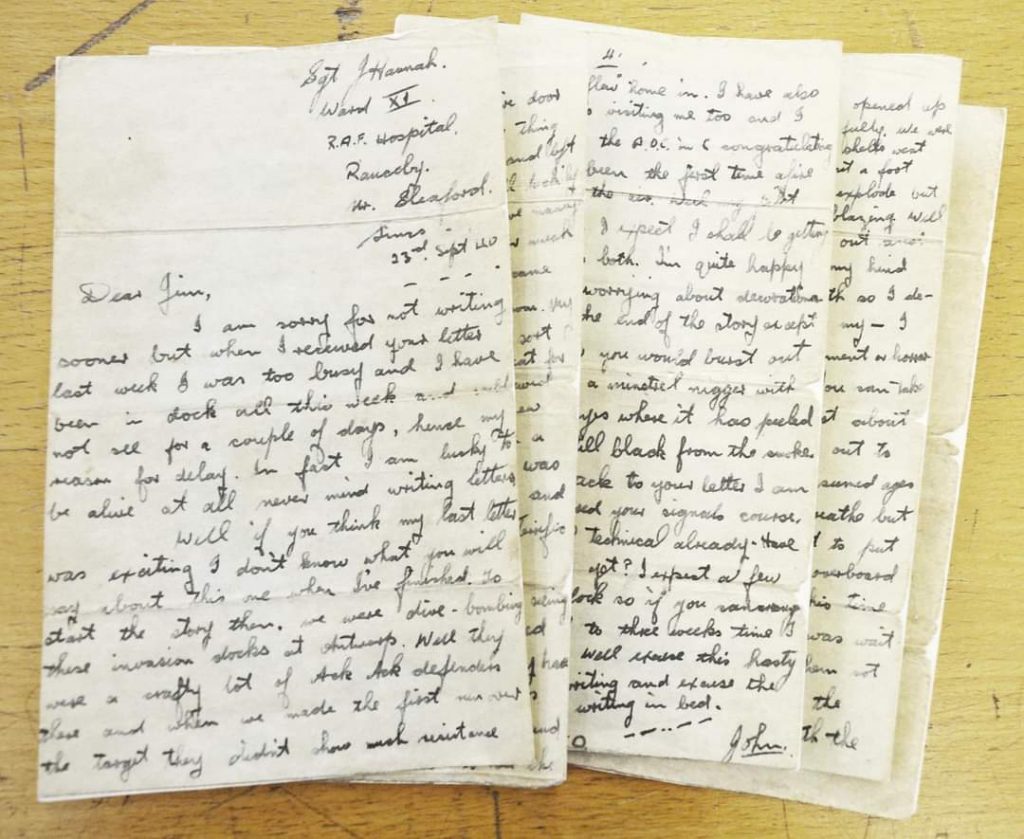

He said in a letter to his parents “I am very lucky to be alive. When we got into a terrible ack-ack barrage, the plane caught fire and my whiskers were singed. It looked as if the plane would blow up. We made for our parachutes, but mine was on fire. By that time, the navigator and gunner had bailed out. The plane was a blazing mess and a perfect target for the ack-ack, which was still batting away. I did some quick thinking and started throwing out parts. During this time, the ammunition on the kite was going off at ten a penny and the heat was terrific.”

Thousands of rounds of ammunition was exploding all around Hannah and he was almost blinded by the intense heat. Air being admitted into the fuselage via the holes made by the ack-ack made the compartment an inferno with all the aluminium sheeting on the floor having melted away.

Using his oxygen mask plus returning to his WOp/AG cockpit for fresh air, he managed to fight the fire for 10 minutes using two extinguishers. Once they had run out, he used his log books and bare hands to successfully put the fire out. He then crawled forward and found that the navigator had also left the aircraft, and passed his log books and maps to the pilot.

On landing at Scampton, the true extent of the damage to the aircraft and the actions of the crew became apparent. The pilot, Canadian Pilot Officer Clare Connor was recommended for a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), the navigator Sergeant Douglas A E Hayhurst was recommended for a Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) and the WOp/AG Sergeant John Hannah was recommended for the Victoria Cross. Unfortunately, the rear gunner, Leading Aircraftman George James didn’t receive any recommendations.

The Air Ministry announced on the 1st October 1940:-

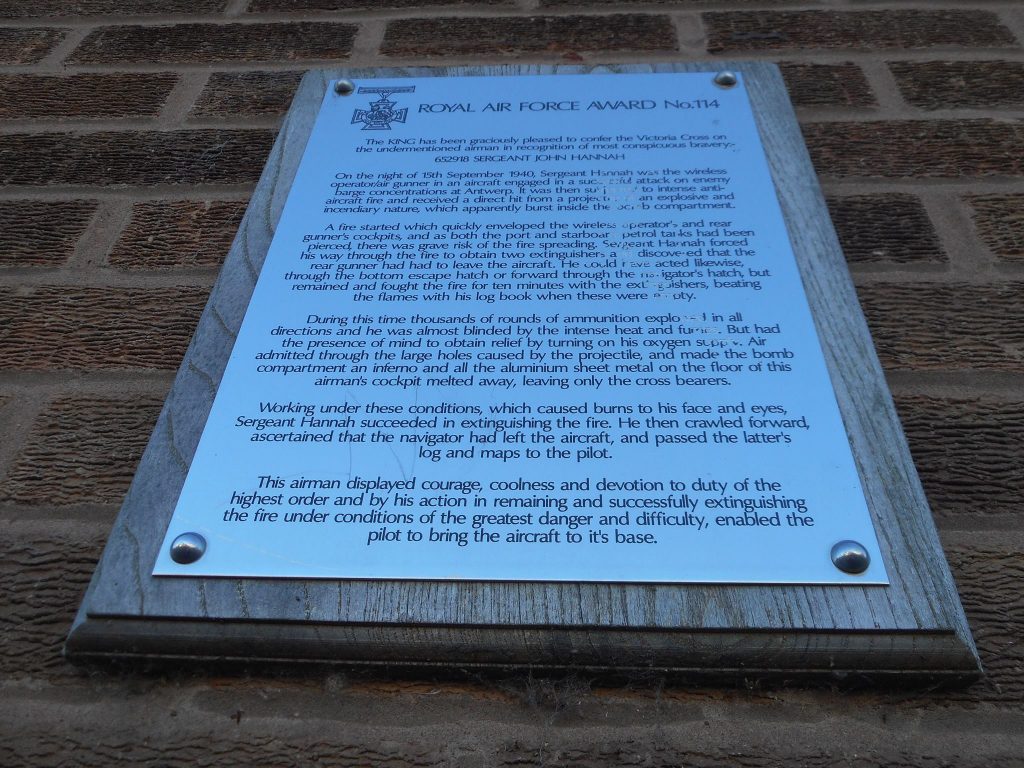

“The KING has been graciously pleased to confer the Victoria Cross on the undermentioned airman, in recognition of most conspicuous bravery:-

652918 Sergeant John Hannah

On the night of 15th September, 1940, Sergeant Hannah was the wireless operator/air gunner in an aircraft engaged in a successful attack on enemy barge concentrations at Antwerp. It was then subjected to intense anti-aircraft fire and received a direct hit from a projectile of an explosive and incendiary nature, which apparently burst inside the bomb compartment. A fire started which quickly enveloped the wireless operator’s and rear gunner’s cockpits, and as both the port and starboard petrol tanks had been pierced there was grave risk of fire spreading. Sergeant Hannah forced his way through the fire to obtain two extinguishers and discovered that the rear gunner had had to leave the aircraft. He could have done acted likewise, through the bottom escape hatch or forward through the navigator’s hatch, but remained and fought the fire for ten minutes with the extinguishers, beating the flames with his log books when these were empty. During this time, thousands of rounds of ammunition exploded in all directions and he was almost blinded by the intense heat and fumes, but had the presence of mind to obtain relief by turning on his oxygen supply. Air admitted through the large holes caused by the projectile made the bomb compartment an inferno and all the aluminium sheet metal floor of this airman’s cockpit was melted away, leaving only the cross bearers. Working under these conditions, which caused burns to his face and eyes, Sergeant Hannah succeeded in extinguishing the fire. He then crawled forward, ascertained that the navigator had left the aircraft, and passed the latter’s log and maps to the pilot.

This airman displayed courage, coolness and devotion to duty of the highest order and, by his action in remaining and successfully extinguishing the fire under conditions of the greatest danger and difficulty, enabled the pilot to bring the aircraft safely to its base.”

His V.C. Award was Gazetted in the London Gazette Issue 34958 page 5788/5789 dated 1st October 1940.

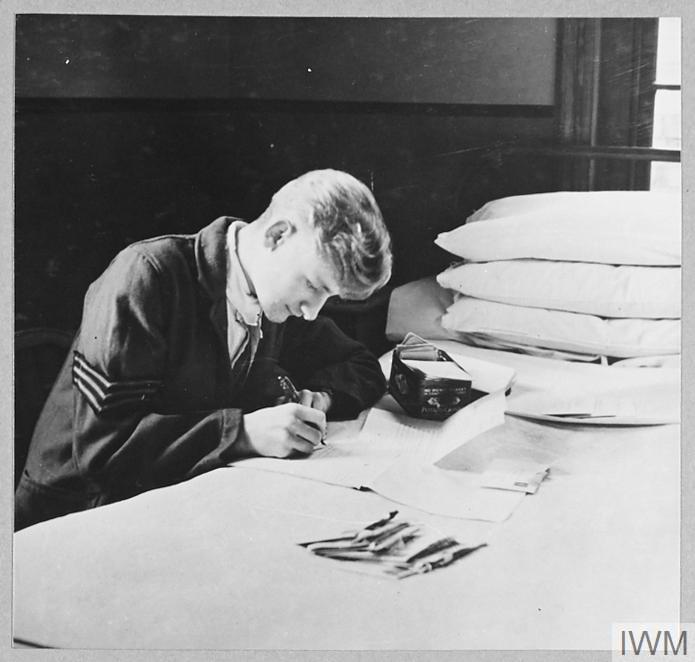

It also became apparent how serious the injuries were to Johns hands and face and he was immediately dispatched to the nearby RAF hospital at RAF Rauceby, just 5 miles South of RAF Cranwell.

John was in Rauceby hospital undergoing treatment for about 3 weeks and whilst there, he said in a letter to his parents “I have had so many C.O’s and big shots visit me that I feel I’m a big shot too.” He goes on to say “Apparently, it was the first time a fire has been put out in the air. My pilot got a DFC, so I expect that I will be getting something too. But if you feel the way I do you will be quite thankful that I am alive without worrying what I am getting or am going to look like. They were worrying about shock when I came in, but I seem to be OK. The only snag I have is that I cannot eat. My skin is all frizzled up. You won’t likely know me when you see me. I have gone thin already and if they change my face, I hope I don’t get lost looking for my home”.

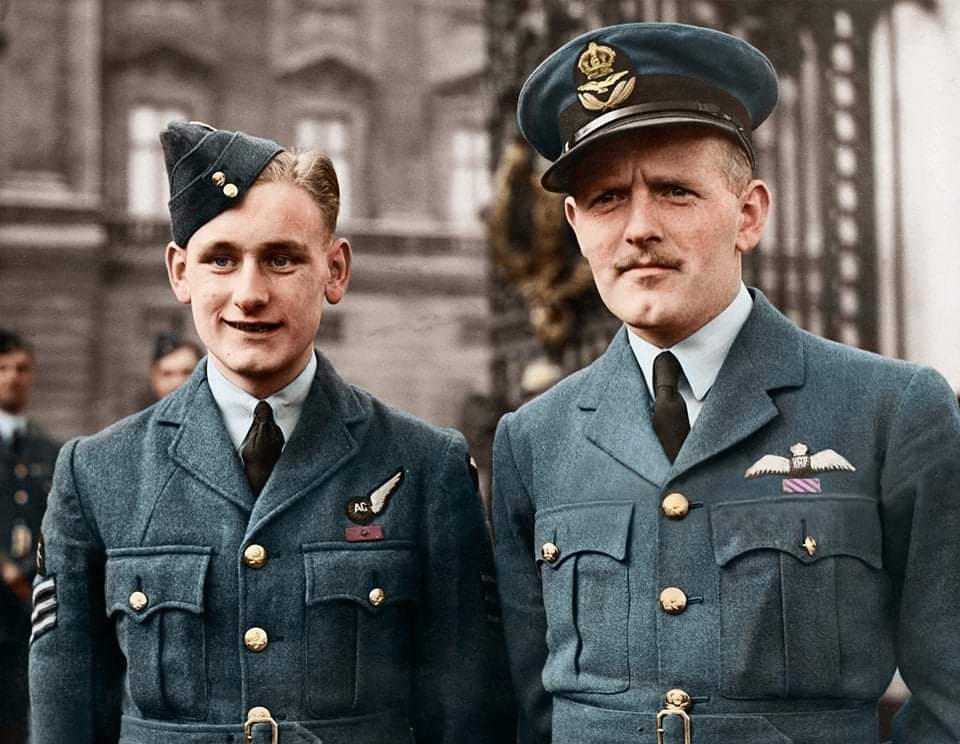

It was whilst a patient at Rauceby that he found out about his award. He was discharged from the hospital on 7th October, and on the 10th he accompanied Pilot Officer Clare Connnor to Buckingham Palace where they received their V.C. & DFC awards from the King.

Sergeant Douglas Hayhurst didn’t receive his award of the DFM as he and the rear gunner Leading Aircraftman George James were now both prisoners of war due to bailing out over enemy territory and imprisoned in Stalag 357 Kopernikus. Both were to survive the war and return to England in late 1945.

Many years later, Douglas Hayhurst was the branch manager of the Eagle Star Insurance Company in Coventry and in 1966 there was an article in the Coventry Evening Telegraph about an annual reunion with a friend from Bristol that began in a POW camp. He recalled the incident when he bailed out “I bailed out, so did the rear gunner. We were taken to a prisoner of war camp. Two weeks later when new prisoners were brought into the camp, we learned that Hannah had won the V.C. We had thought the aircraft crashed. They told us that Hannah’s chute was burnt and he could not get out and the pilot stayed with him.”

On the 2nd November, the Strathearn Herald published a poem “A Schoolgirl’s Appreciation of Sergeant John Hannah V.C.”

O noble John Hannah, how much we admire you,

With your wonderful coolness and courage so true,

When you stayed in that ‘plane all riddled with bullets,

And fought with the flames which were eating it through.

O what did you feel in that terrible air-flight,

When the gas and the smoke must have blinded your sight?

Or were you benumbered by the sense of great danger?

And did you just do what you thought to be right?

O how joyful and proud will your dear mother be,

When she hears how you gallantly won the V.C.,

Her Brave son in safety she’s longing to see.

S.M.C.D.

Following his discharge from hospital, John didn’t return to operational flying and on the 4th November 1940, he was posted to No 14 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RAF Cottesmore as an instructor.

Before he was posted to 14 OTU, he had public duties to perform as the Guest of Honour to Lord Hamilton of Dalzell. He had been invited along with his younger brother and their parents to the official opening of the German Junkers 88 exhibit at Motherwell to raise money for their Spitfire fund.

In March 41, more public duties followed when John was presented to the workers of an aircraft factory by the aircraft designer Mr Frederick Handley Page. It was reported that when he met the staff in the lunchtime break, they wanted him to speak and all he could say was “Thank you. I am very glad to be with all you boys and girls” due to being scared of the audience.

John Hannah and another V.C. winner from Scampton, Flight Lieutenant Roderick Learoyd of 49 Sqn, were honoured in a ceremony at the Scampton Base. As both men had won their V.C.s whilst operating as crew members on the Handley Page Hampden bomber, the aircraft designer Mr Frederick Handley Page, commissioned Mr Frank O Salisbury to paint their portraits.

The paintings were presented to the two men at a ceremony at Scampton by Mr Frederick Handley Page on 21st June 1941. At the ceremony, both airmen immediately handed the painting over to the Station Commander for safe keeping. Among those present at the ceremony were Air Vice-Marshal Arthur T Harris and Air Vice-Marshal Norman Bottomley who were both later to become Air Officer Commanding In Chief Bomber Command.

This wasn’t the first time he had had his portrait painted as back in October, shortly after his award of the V.C., his portrait was painted by the official war artist Eric Kennington.

Whilst at Cottesmore, John started a relationship with a local girl from Oakham by the name of Janet Beaver whose father was awarded the Military Medal whilst serving with the 5th Leicestershire Regiment during the First World War.

On Saturday 21st June 1941, Janet and John got married in secret at Oakham Register Office. The Sunday Mirror on the 22nd June published a feature on their wedding and a photo of the happy couple. It stated “Sergeant John Hannah V.C., nineteen-year-old RAF, bomber hero, was shy over his decoration, but shyer still over his wedding yesterday. He married Miss Janet Beaver, of Oakham, at the register office in that town and he had made careful plans to keep his romance secret.”

The Wednesday after his wedding, John was undertaking more public duties when he attended the Headquarters of the Market Harborough and District Air Training Corps where he and Squadron Leader J E C G E Gyll-Murray met the district flights of Market Harborough and Kibworth at the County Grammar School and made speeches to the cadets. After the speeches, there was great competition between the cadets to obtain the autographs of the two airmen, who duly obliged.

John stayed at Cottesmore until September 41 when he was promoted to Flight Sergeant and posted from 14OTU to No 4 Signals School at RAF Yatesbury as an instructor.

In November 1942, John was medically discharged from the RAF with a full pension as a result of being to unfit to serve due to his health deteriorating and the onset of Tuberculosis (TB) brought on from his injuries sustained in the fire.

John and his wife Janet and their children set up home in Birstall on the outskirts of Leicester. It was around this time that John had joined the Leicester Branch of the Royal Air Forces Association. On Friday 15th January 1943, John attended a ball held at the Palais de Danse in Leicester for “warriors of the present battles of the skies” sponsored by the old pilots and observers of the Royal Flying Corps on behalf of the Leicester branch of RAFA.

The Daily Record reported on 23rd January 1943 that he had been discharged from the RAF and the article went on to quote him as saying “I have been given a pension for a year. It will be reviewed at the end of that time after I have been before a medical board. I have a 100% pension, just now – £3 7s. 3d. a week for himself, his wife and his child.”

Asked why he is in Leicester, he pointed out that his wife was from Oakham and had worked in Leicester. He went on to say “I am here, also, because of the official attitude in Glasgow towards me. When I won the V.C., they had the bands out for me, but little has been done for me since. The people of Leicester have done more for me in a week or two than Glasgow has done for me in a long time. Dances and other functions are being organised for a testimonial fund for me, and I much appreciate what the people here are doing for me – so different from Glasgow.”

The Lord Provost of Glasgow, Mr John Riggar, expressed great surprise that Sergeant John Hannah V.C. should criticise official Glasgow. He stated “I have heard nothing of Mr Hannah from the time before I took office. That was over a year ago, when I believe, he was being recommended for a commission. We have not heard anything from him at all, and did not know where he was.”

Another article a few days later in the Daily Mirror quoted him as saying “I long to be back in the Royal Air Force again and to fly with the boys. After getting my V.C. I had two serious crashes and had to come off flying. My nerve gave way and I could not carry on, and was discharged. I love being home with my wife and daughter, but I should prefer to be behind my gun in the air. The medical authorities have told me I must not work for six months. I am now taking life easy and passing time giving short talks on flying, as I cannot forget the RAF. Everyone has been very kind to me, both at my home town in Glasgow, and here in Leicester.”.

Since being discharged from the RAF, he had returned to Glasgow to look at businesses in the area and had numerous offers of employment from various people in Leicester, but he had turned them all down as he wanted to concentrate on improving his health.

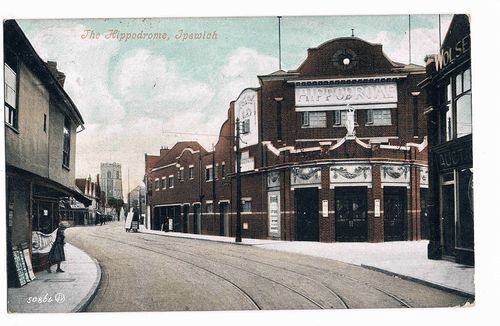

However, due to his much-reduced income, he had decided to take to the stage and his first appearance would be at the Hippodrome Theatre in Ipswich starting on Monday 15th February 1943. His stage manager was comedian Len Childs who introduced him to the audience.

His turn came about halfway through the show, just after a knockabout turn by the Tracey Brothers and O’Leary. The curtain went down on O’Leary singing “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime” and swung up again on Len Childs singing “Lords of the Air”.

After his opening song, Childs went on to say: “I would Like to pay tribute to the Air Force, of which I was a member in the last war”. With that and amid cheering, Hannah walked on stage wearing his RAF Flight Sergeant uniform with his Air Gunner’s badge and V.C. ribbon.

Hannah told the audience a funny story about when he was a ‘Rookie’, another about his first flight and then about the flight during which he won the V.C. for batting out the flames with his bare hands over Antwerp. Afterwards he saluted the audience and marched off to whistle and applause to autograph the photos of himself which were being sold for 2s each in aid of the RAF Benevolent Fund.

After his debut, he told the Daily Mirror “I have a wife and kiddie in Leicester, and I need the money. My pension is £3 7s. 3d. a week and I have been living on the £70 I saved while I was in hospital. I am receiving treatment for tuberculosis, and I cannot make a regular stage contract because I do not know how I shall feel”.

The first few nights of his shows he appeared on stage wearing his RAF Uniform, but after the show on Friday, he was approached by an RAF Officer accompanied by a Police Officer who told him it was illegal for him to wear his Flight Sergeant uniform and that he would be prosecuted if he continued to do so. After the show, he went with the officers to the Police Station where the regulations were read out to him.

On the Saturday, he appeared on stage wearing civilian clothes without his V.C. ribbon. Instead, he wore the badges of the British Legion and Royal Air Forces Association on his jacket lapels.

Even though he said he cannot make a regular stage contract due to his ongoing treatment, he still undertook public duties as the week after his Ipswich stage shows, he was touring Munitions factories on behalf of the Ministry of Information.

The dispute over Glasgow’s support towards John continued throughout 43 and in March 44, Johns father, James wrote to the Sunday Post “To the Editor of the Sunday Post. I am the proud father of John Hannah, first and youngest V.C. of this war. I read your article on Carluke doing its V.C’s proud. There are many conflicting rumours about Glasgow’s recognition of my son. It has been said that he got £500 from Glasgow, and even as much as £1000. I would like to make it known that he received £25 in War Savings Certificates from the people of Knightswood and a wallet containing £12 from the personnel of Victoria Drive School. That was all, apart from a few personal gifts. I hope this letter will put an end to the rumours. James Hannah.”

Over the next couple of years, John took up employment as a taxi driver when he and a friend purchased two cars and started the taxi business. It was a struggle for them and the business was wound up in early 1945.

In January 1945, John branched out and opened his own cycle shop in Leicester.

Unfortunately, by 1947, his health had deteriorated to such a state that he became bed ridden in January 1947. By this time, Janet & John now had three daughters: Josephine, Jacqueline and Jennifer.

In January, Mr A E Carr, of Victoria Street London, who was a Cpl Instructor with John at Yatesbury in 1943 put out a call to the public to subscribe to a fund to send him to Switzerland for treatment.

Mr Carr told a reporter “if the Government at this late date cannot see their way clear to do what I am sure all air crew and indeed the whole of the Royal Air Force, believe to be their duty, then I think we members of the public, who are now being thanks for raising £7000 for China relief in cinema collections over the last few days should demand that a similar appeal be made immediately.”

Mr Carr goes on to say “Shy and reserved, he was persuaded to travel the country giving talks in aircraft factories and other war plants. We knew he hated this duty, but it was probably that experience which gave him the courage to go on music hall stages to try and earn sufficient money, not only to maintain his wife and children but to pay the expense of his treatment.”

As a result of the appeal being launched, a Government official from the Ministry of Pensions was instructed to visit John and his family to find out what help he needed. They had heard that he had to be fed on milk, brandy and eggs and that his wife was struggling to make ends meet. The People newspaper published on 27th January 1947 reported that they had been informed by a Ministry official “We are looking into his case immediately to see if we can give extra aid through the King’s Fund, and, possibly, an increase to his pension.”

The recent newspaper reports about Johns deterioration in his health also stimulated another former RAF airmen into trying to provide help and assistance. Mr Norman Dodds, who was an ex-ranker, was the MP for Dartford and the President of the Dartford branch of the Royal Air Forces Association had been in touch with his Czech friends in London who were in discussions with their Government in Prague about getting an invitation for John to go to one of their sanitoria and that the Association were prepared to pay the costs. However, John didn’t want any of this as his response was “I appreciate what Mr Dods and my old RAF friends are doing. I don’t want to seem ungracious, but I have always tried to stand on my own feet. If I go anywhere, I prefer Switzerland.”

John told a newspaper reporter that “I have had offers to go to Switzerland, but my doctors are against me taking the risk of making a journey to Switzerland or Czechoslovakia. I would prefer to go to the Swiss mountains but if I did so, I would have to accept the responsibility. It is heartening to know so many people are willing to help, and I hope they will not think I am ungrateful if I say I would like to go under my own steam. I have been advised to enter a local sanatorium, where I can build up my strength, but I believe I can do that by resting at home. There the matter must rest at the moment.”

When advised of Johns views, Norman Dodds replied “The offer remains open, and if at any time he is able to accept, Mr Hannah’s old colleagues of the RAF will be only too happy to render every assistance possible. I hope to visit Leicester shortly, and will state our views personally to him.” Mr Dodds mentioned that for some time, negotiations had been in progress between representatives of the Czech Government and Squadron Leader A J O Warner, Secretary of the RAF Association, for sick RAF men to visit Czechoslovakia for medical treatment.

A few days later, Norman Dodds visited John in his Birstall home and reported that John was frank about his attitude. He does not seek charity nor want it, and he cannot rid his mind of the thought that in some way he would be accepting charity by taking advantage of the offers made. Norman went on to say that “The Leicester Branch of the RAF Association are in close touch with the position, and in view of the several requests made to me to convey help to the V.C., I point out that Flying Officer W F Watson, Chairman of the Leicester RAF Association, will deal with these if made direct to him at the branch headquarters, Charles Street, Leicester.”

John was admitted to Markfield Sanitorium on 31st January 1947 after being seriously ill in bed at home for several weeks. His wife Janet, as well as looking after their three daughters, had also been his nurse at home.

The Markfield Sanitorium or Markfield Hospital was the County Sanitorium and Isolation hospital on Ratby Lane and was opened in September 1932 by Sir George Newman, the Chief Medical Officer to the Ministry of Health.

It had 203 beds in six wards, with isolation for fever patients and a sanatorium for patients with tuberculosis (TB). Fever patients were usually children, with fevers including diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhoid, smallpox and meningitis. Those with TB were mostly between aged 17 and 26 or were older people.

Stays were often lengthy, with TB patients there for up to two years. This was before more effective medicines became available, with the main treatment for TB being lots of bed rest, good food grown on the hospital farm and fresh air – patients were exposed to the Markfield winter air and snow too! Medical treatment for TB included PAS, an unpleasant medicine taken four times daily, streptomycin injections and air treatment for the lungs.

She had been overwhelmed by the large numbers of telephone enquiries and offers of assistance she had received at their home in Stonehill Avenue Birstall. “My husband’s illness has brought in its train inquiries and offers of practical help, not only from neighbours and friends, but from well-wishers in all parts of the country. The number has been legion, and it is beyond my powers to answer each one individually. I do hope that through the Evening Mail, many of them will learn of my heartfelt appreciation of their kindness.”

Mr Neil McKinnon Willmot, a veteran of Alamein and who was now a farmer in the Cape Province region of South Africa offered his home to the Hannah family. He said that if Hannah could be brought out to South Africa, he, as well as his family, could remain at his farm until he got better. He felt certain the South African climate together with plenty of good food would cure the RAF hero.

The Leicester Evening Mail on the 7th June 1947 reported that John had passed away in Markfield Sanitorium. Johns wife Janet, told one of their reporters “he was too proud to accept anything that had the appearance of charity. He had lived to regret having the V.C.. It meant nothing to him. All he wanted was good health and a chance of happiness with the children.” John was receiving full disability pension of £4 5s. a week for himself and his family and was in the process of buying the family home through a building society when he died. His wife Janet went on to say “It will be a struggle and I’m worried about the children’s education, but I’m not able to think of anything at the moment, except that I shall never see John again.”

On hearing the news of Johns death, Flying Officer W F Watson, Chairman of the Leicester RAF Association conveyed to Janet, on behalf of the whole of the membership of the Association, their deepest sympathy in her loss.

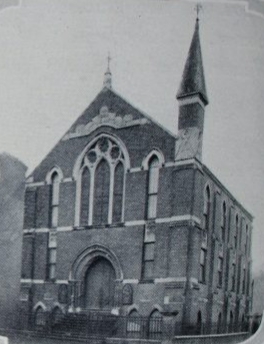

The funeral service was arranged for Wednesday 10th June, ironically, the day of his daughter Jacqueline third birthday. The service would be held at St James the Great Church in Birstall commencing at 1:30pm followed by the internment in the church cemetery.

The service was officiated by the Reverends Francis Pratt, the vicar of St James the Greater and Reverend Charles A Turner, Rector of Broughton Astley and Padre to the Leicester Branch of the RAF Association. The funeral arrangements were discussed with the Air Ministry, local units of the Royal Air Force and Air Training Corps.

At his funeral, the coffin was draped in the RAF Ensign and carried by a bearer party of RAF personnel from nearby RAF Wymeswold. The station also provided a firing party under the command of Squadron Leader C Wright from the base. The Leicester Air Training Corps Squadron provided drummers and trumpeters who sounded the Last Post. A contingent of RAF personnel also attended from RAF Leicester East airfield.

The family mourners were: Mrs Hannah, widow; Mr and Mrs James Hannah, parents; Mr James Hannah, brother; Mr Hugh McColl and Mr John Hannah, uncles; and Mr and Mrs Arthur Beaver, father-in-law and mother-in-law.

Among those present were Mr Montague Turnor, Mr Craston White, Mr Dick Kerr, Miss Henson representing SSAFA, Group Captain A P Ellis, representing the RAF Benevolent Fund; Mr R D Buxton, hon. Secretary and members of the Leicester Branch of the RAF Association, Mr J P Moore, chairman; Mr C Williams, vice-chairman; and members of the Birstall branch of the British Legion and Flying Officer W F Watson, representing the Leicester ATC.

The Nottingham Journal published an article on the 10th June “Immediate Pension for V.C.’s widow. Because it was first thought that her husband was a Sergeant (instead of Flight Sergeant) the Ministry of Pensions announced yesterday that Mrs Hannah, widow of Britain’s youngest RAF V.C., who died in Markfield Sanatorium (Leics.) on Saturday, would receive personal allowance of 37s. She will in fact get 38s. a week. In addition, she will receive 11s. for each of her three daughters and another 5 s. for each of the younger two. This makes a total of £4 1s. compared to the nearly £7 a week which John Hannah received while alive.”

Children’s Education but Mrs Hannah will be eligible for a rent allowance (maximum 15s. a week) and can also apply for educational allowances for the children. “Mrs Hannah has already filled in the necessary application forms” said a Ministry of Pensions official “and we shall make her a provisional allowance to help her and the children until such a time as the procedure is completed and then make any necessary adjustments.”

Following John’s death, a fund had been opened in Leicester to support Janet and her children. Money was donated from various things and in July the Fleckney British Legion Women’s Section donated £4 from the proceeds of a whist drive that they held in the school.

The setting up of this local fund had caused questions to be asked in the House of Commons. Air Commodore Arthur V Harvey, MP for Macclesfield, asked the Minister of Pensions, Mr J B Hynd, after he had announced the amount awarded to Janet “Do you consider that the pension is suitable for a man who served his country so conspicuously?”

Mr Hynd said that the pension and allowances amounted in all to £3 17/- a week. In addition, the normal family allowance of 10/- weekly was being paid. Mrs Hannah had been invited to apply for an education grant. The pension was the maximum payable under the Royal Warrant.

Mr Barnet Janner, (Soc Leister W.) asked – “Are you aware that owing to the very serious condition in which the widow and children find themselves, a public subscription list has been opened in Leicester and will you do what you can to see that this very deserving case is looked into quickly?” Mr Hynd said he was not aware of the circumstances being so hard as suggested.

John Hannah is commemorated in different ways. As mentioned at the start, at the head of his grave at St James the Greater churchyard, is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone showing the V.C. medal. He is also commemorated on the Birstall war memorial at St James’.

There are also a couple of other memorials to him in Birstall, the first being a row of shops being named Hannah Parade and there you will find a memorial plaque with his V.C. citation.

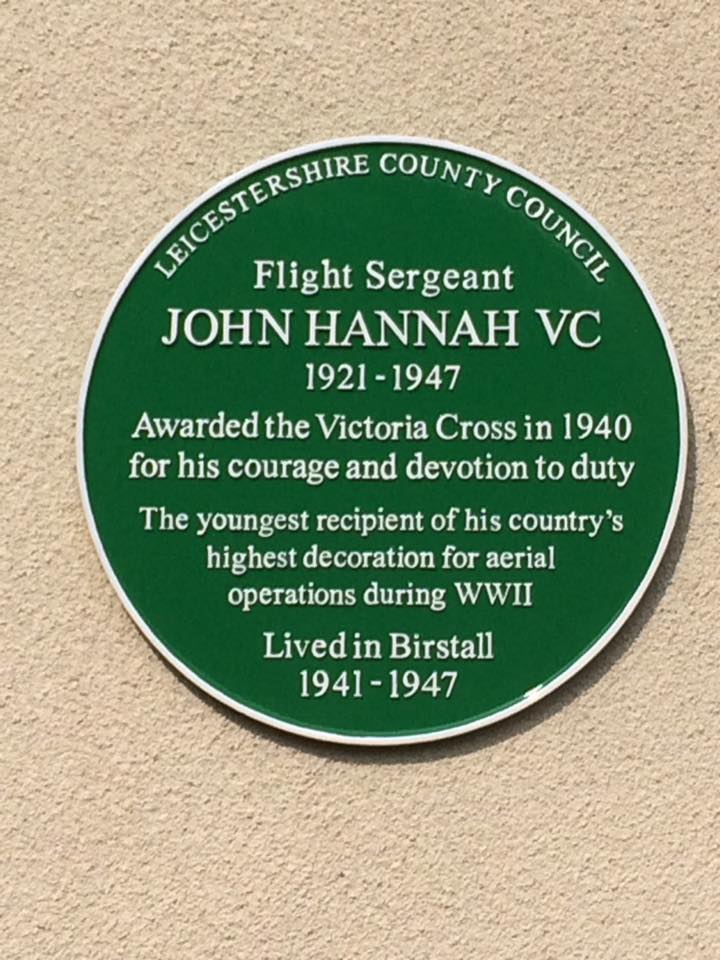

On the 15th September 2016, a green plaque was unveiled at the Royal British Legion in Birstall.

In 2007, a new memorial stone commemorating the Victoria Crioss recipients from Paisley was unveiled and dedicated in Hawkhead Cemetery. The meorial contains the names of 5 Paisley men who won the VC, 2 from the Crimean War, 2 from WW1 and John from WW2.

On VE Day 2020, Johns relatives attended the dedication of five memorial trees and plaques commemorating members of the Army, Royal Navy and RAF that were unveiled at the veterans’ monument in Knightswood, Glasgow.

A Rose Garden has been dedicated with special roses in memory of JOhn at the St John the Baptist Church Scampton.

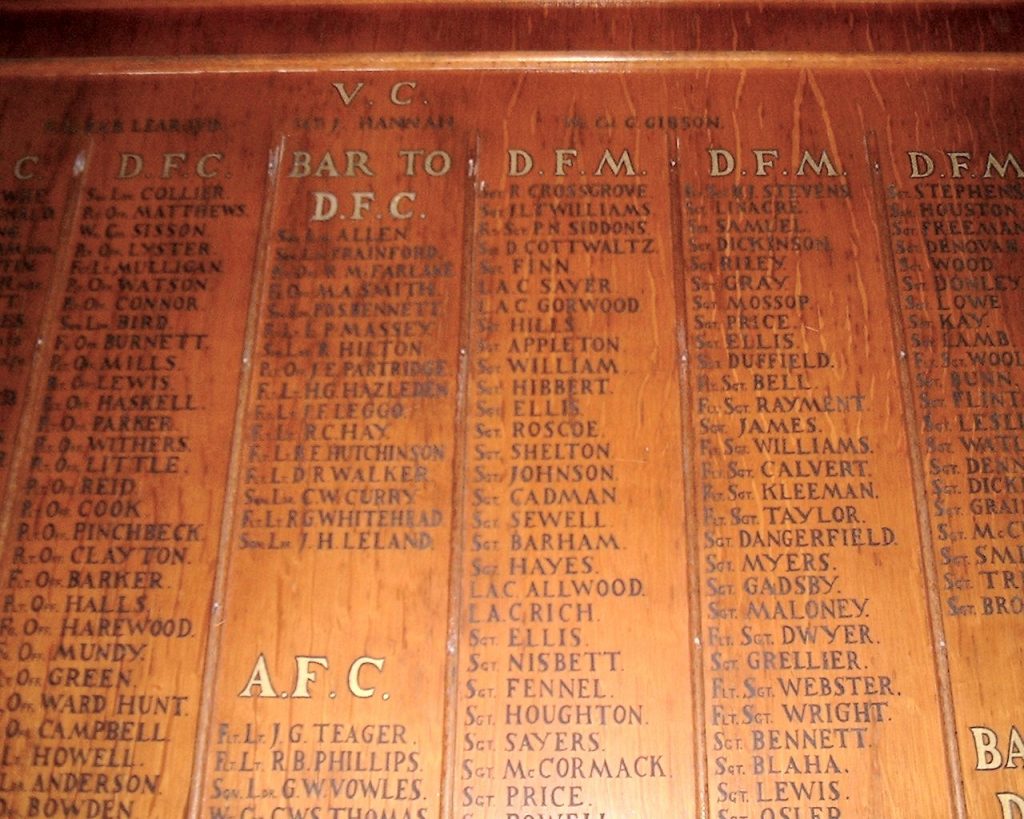

Inside St John the Baptist Church Scampton there is the Honours and Awards Memorial Board from RAF Scampton on which John is name as one of the VC winners along with Flt Lt Learoyd & Wg Cdr Guy Gibson.

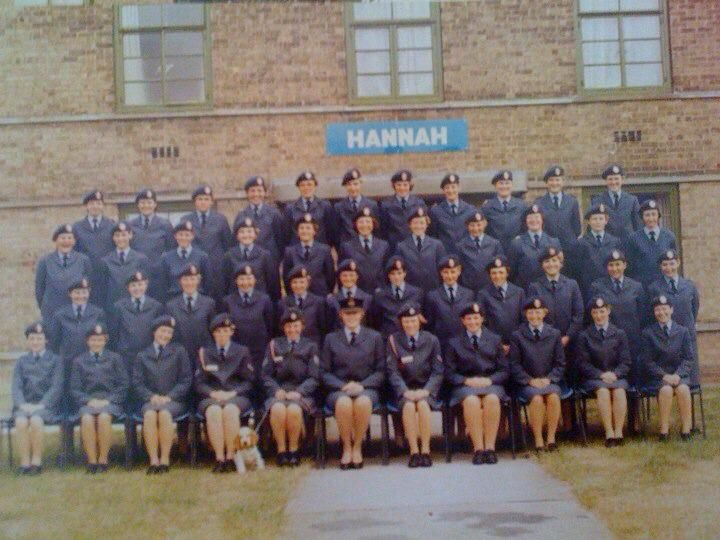

At RAF Swinderby, one of the accommodation blocks was named ‘Hannah’ in honour of John.

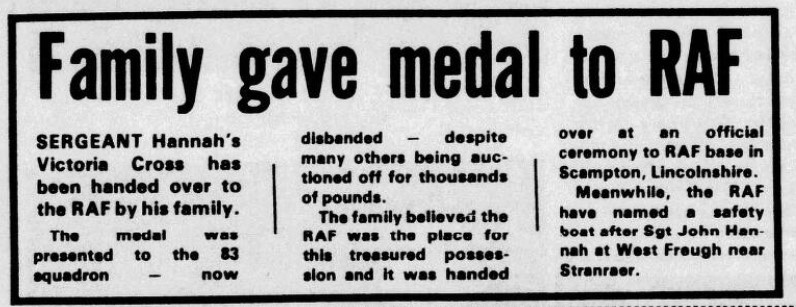

The RAF also named a rescue boat Sgt John Hannah at West Freugh near Stranraer in Scotland.

A trophy, initiated by Ron Durran, a former Cadet Airmen who was instructed by John at Yatesbury has been introduced at John’s old school, the Victoria Drive Secondary in Scotstoun, Glasgow for the ‘most distinguished pupil’.

At the RAF Museum in Hendon, there is a dispolay of a few of Johns items. As mentioned poreviously there is a letter he wrote to his brother whiolst in hospital. The dispaly also included his Flying Helmet and Goifggles and intercomm/mic tel lead plus his VC Medal that his wife Janet donated to 83 Squadron.

In 1953, John’s widow, Janet was allocated one of the four seats at Westminster Abbey for the Coronations of Queen Elizabeth II. The four seats had been reserved for widows of United Kingdom V.C.’s through the Ministry of Pensions who provided accommodation in London and provided transport to take her to the Abbey.

The Leicester Illustrated Chronicle published an article in January 1956 about Janet and the three girls. “Sergeant John Hannah who won the V.C. at the age of 18 and died at 25, was a modest man. But he would be proud of today. Proud of the wife and family he left at 87 Stonehill Avenue, Birstall. Proud of their courage, their ambitions – and their happiness.” In the article, Janet says how life was grim after his death and she had to sink or swim. She supplemented her pension of about £4 by doing hairdressing for friends. The Leicester Mercury organised a fund to help make life easier for the fatherless family “And the Ministry of Pensions and the RAF Association have been good to me” she said. The article finishes by saying “But his widow, who has so squarely faced the challenge to her own bravery, and those three fine children carry on the Hannah reputation for courage.” To read the full article click here: Leicester Chronicle 28 January 1956

On Tuesday 26th June 1956, Janet joined in with the ceremony where 300 V.C. recipients paraded in Hyde Park. The ceremony was an echo of the great parade that took place 99 years previous when Queen Victoria, accompanied by the prince Consort, rode to Hyde Park to present the V.C. to 62 men which she instituted.

Also, at Hyde Park with Janet were six V.C. winners from Leicestershire: Lt-Col John Cridland Barrett V.C.; Captain Tom Steel V.C.; Captain Robert Gee V.C.; The Rev Arthur Proctor V.C.; Robert Edward Cruikshank V.C. and Richard Burton V.C.

At the same time as the Queen made her speech, a poppy wreath was laid on John’s grave in Birstall. The Queen said “Today, I am proud to stand here, with men and women from all parts of the Commonwealth, to do honour to the successors of that gallant band, to the 300 brave men who are present and to those who can be with us only in spirit, or in the memory of family and friends.”

By 1962, Janet was looking at trying to stand on her own two feet instead of relying on charity and she was considering selling her husbands V.C. in the hope that it would raise £1,000 so that she could start her own hairdressing business. Her daughter, Josephine who was now 19 and married, told the Daily Herald “She’s had a tremendously hard fight bringing us up. Now all she wants is security. She’s grateful for the help she has received but she wants to make her own way now”. Officials from the RAF Association contacted Janet in the hope that the association’s financial aid may persuade her not to part with the V.C.

Janet had received offers around £1,000 for the medal from all over the UK including the Imperial War Museum. She had even turned down an offer of nearly £1,750 from an individual in New York plus offers from Australia, New Zealand and parts of Europe.

“I want to make sure it goes to the right place. I don’t want to cash in on the medal. I simply want to raise enough money to start a hairdressing business and preserve my independence. The money will be shared with my three daughters. They have agreed this is the right thing to do. The second eldest wants to train as a hairdresser. I have been a widow for 15 years and it has been a struggle to make ends meet. I could go on another 15 years and still be in the same position. Without immediate capital, I could not start a business and selling the medal is the only way I can raise it. My husband was a practical man and I am sure he would have approved.”

An unexpected offer of help came in from a former World War One pilot meant that she may not have to sell the V.C. Mr S Burgess of Worcester was the principal of the Worcester School of Hairdressing and offered to give Janet as long a refresher course in hairdressing as she needed and providing her with accommodation during training. At the same time, his friend, Mr W Calway who was a manufacturing chemist had offered to provide her with £1,000 worth of hairdressing equipment. Mr Calway stated “We felt full of compassion for her in having to sell the V.C. and considered something should be done to help her in her predicament. There are no strings attached to these offers and Mrs Hannah may pay for the equipment whenever she can without the addition of any interest.”

Janet and her three daughters agreed not to sell the V.C. stating “I’m tired to death of all the worry and publicity my family has received. It was never intended this way. All I wanted was security for myself and family.”

After declining many offers for her husband’s medal, she eventually decided to give it away free by presenting it to John’s old Squadron, No 83 Squadron who had reformed and were back at RAF Scampton operating the Vulcan bomber. She said “Naturally, there were times when I was tempted to sell the medal. I’m glad I kept it, and I feel I am doing the correct thing in donating the V.C. to John’s old Squadron. I think they should have it for safe keeping.”

Johns Victoria Cross medal and several of hid belonging including his flying helmet, mic-tel lead and goggles plus a letter he wrote to his brother are now on display in the RAF Museum at Hendon.

In the Illustrated London News published on 1st September 1979, they published an article by John Winton titled “The high price of valour” – The qualities that make a man a hero in war do not necessarily fit him for a successful life in times of peace. The author looks at the sad histories of some winners of the Victoria Cross.

The article looks at various V.C. winners and how they coped after leaving the military and John Hannah is one of those mentioned.

“Suicide rates among VCs have dropped drastically since the horrific levels of 100 years ago; the last were two first World War VCs, in the 1950s. But memories are notoriously short (only a few years after the Armistice Boy Cornwell’s grave was found overgrown and neglected) and even in modern times life has not been easy for some VC’s. Officers seem generally to have prospered; Sir Tasker Watkins is a judge and Leonard Cheshire found a second fame as a philanthropist.

But for some, other ranks the going has been much harder. Private Speakman, the Korean War VC, found it extremely difficult to settle down in civilian in life. John Hannah, the 18 year old RAF Sergeant who won a VC for putting out a fire in a Hampden bomber over Antwerp in 1940, was hard pressed to support his young family after the war and died in a sanatorium aged 25.

Leading Seaman Magennis, the ‘frogman VC’, was the only Ulster VC winner of the Second World War and he was naturally feted when he went home to Belfast. But he and his wife soon spent the money raised for them and Magennis sold his Cross for £75. “We are simple people” his wife said. “We were forced into the limelight” Ian Fraser, Magennis’s captain, who also won the VC in the same exploit, put the problem in a nutshell: “A man is trained for the task that might win him the VC. He is not trained to cope with what follows.”

Going back to the question in the opening paragraph –“What is Courageous Duty?” Does it only apply to you while serving and something you carry out as part of a task that you have been trained for, or does it apply after you leave the service and apply to your duties of supporting your family?

I think that following his injuries, John and his wife both showed courage in their duties fighting Johns illness and supporting their family, especially Janet when she was having to nurse John and later bring up the three daughters all on her own with very little income.