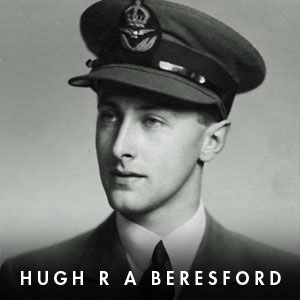

In Blog 22, I looked at the story of Flt Lt Hugh Richard Aden Beresford and how his body was recoevered forty years after being shot down in his Hurricane fighter.

In this blog, I look at some of the other Beresford family members that made the ultimate scarifice serving their country.

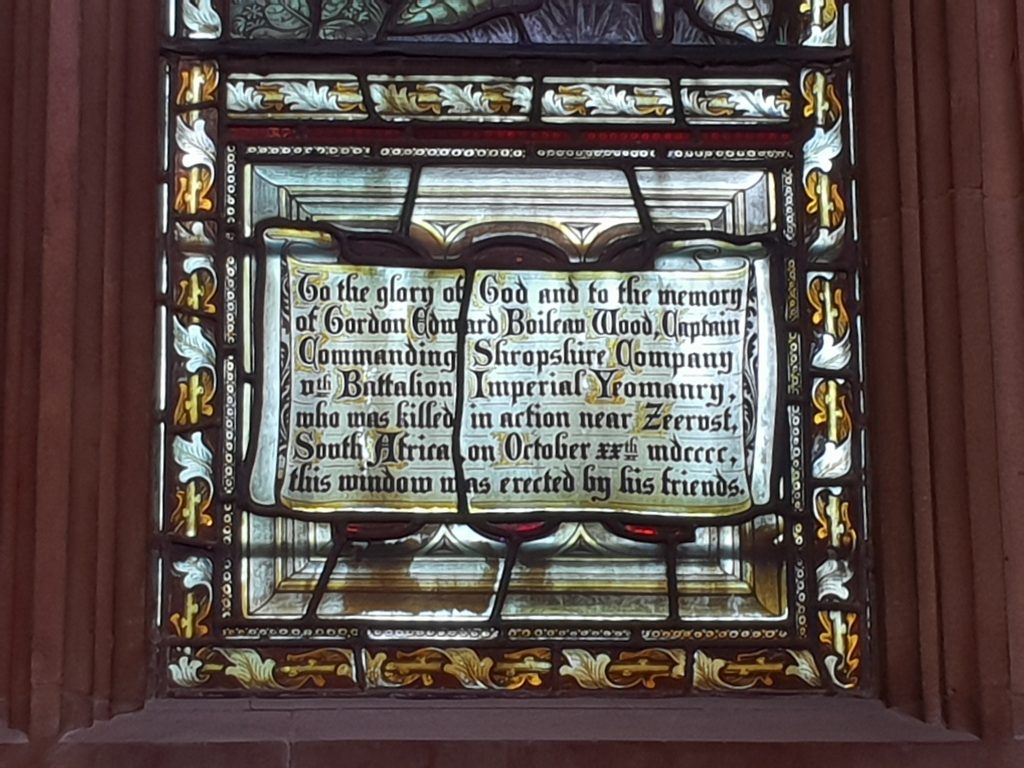

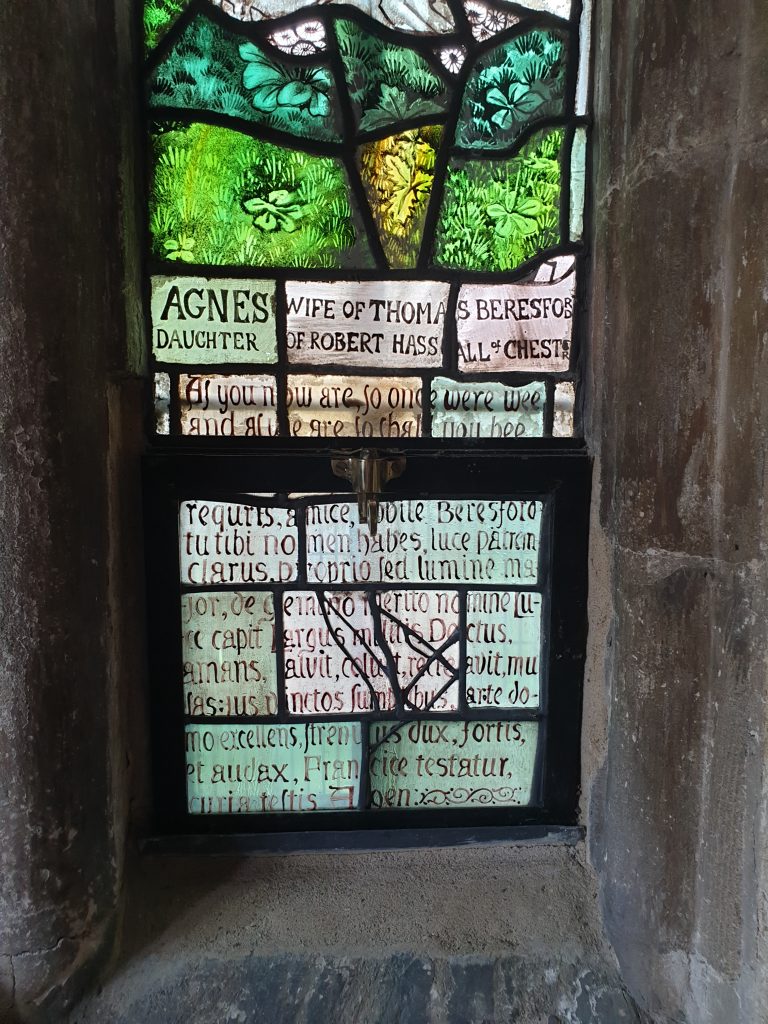

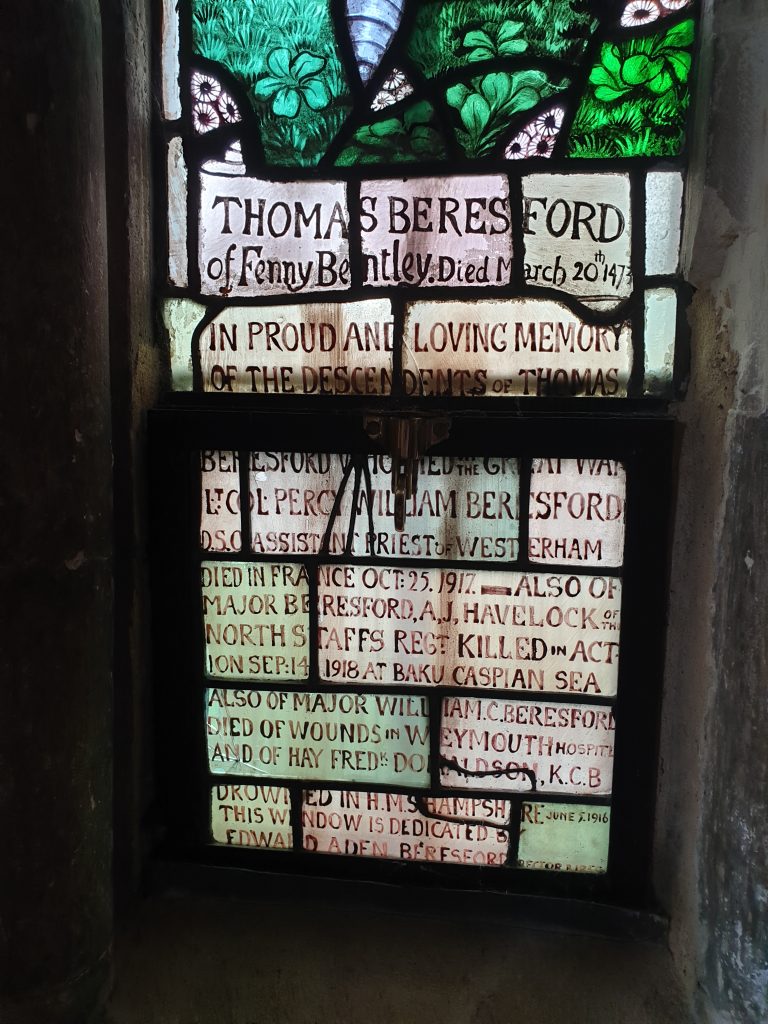

Opposite the Memorial to Hugh, his father and grandmother, you will see the stained-glass window, appropriately named the South Chancel Memorial Window, and as its name suggests can be found in the South Chancel and was installed in the early 1920s. It was gifted to the Church by Hugh’s grandparents, Rev Edward Aden Beresford and his wife Annie Mary Beresford and their initials appear at the very top of the window.

The Beresford family have been Rectors for Hoby cum Rotherby for many years since Reverend Gilbert Beresford became Rector in 1838. He married Anne Browne, the only daughter of Rev Henry Browne of Hoby, in 1805. The last Beresford to hold the post was Hugh’s father the Reverend Hans Aden Beresford.

The bottom panels of the window lists the members of the extended Beresford family who were killed whilst serving their country during the First World War and as such, it is classified as a war memorial by the War Memorials Trust and the Imperial War Museum.

The Beresford’s commemorated on the window are all descendants of, or married to descendants of, Rev Gilbert & Anne Beresford.

The inscription on the light windows reads:

THOMAS BERESFORD OF FENNY BENTLEY, DIED MARCH 20TH 1473 IN PROUD AND LOVING MEMORY OF THE DESCENDENTS OF THOMAS BERESFORD WHO DIED IN THE GREAT WAR LT COL PERCY WILLIAM BERESFORD D.S.O ASSISTANT PRIEST OF WESTERHAM DIED IN FRANCE OCTOBER 25 1917 – ALSO OF MAJOR BERESFORD A.J. HAVELOCK OF THE NORTH STAFFS REGT KILLED IN ACTION SEP 14 1918 AT BAKU, CASPIAN SEA. ALSO OF MAJOR WILLIAM C. BERESFORD DIED OF WOUNDS IN WEYMOUTH HOSPITAL AND OF HAY FREDK DONALDSON, K.C.B./ DROWNED IN H.M.S. HAMPSHIRE JUNE 5TH 1916 THIS WINDOW IS DEDICATED BY EDWARD ADEN BERESFORD RECTOR FROM 1855 AND HANS ADEN BERESFORD BORN 1884

Who were these members of the extended Beresford family that made the ultimate sacrifice during World War One?

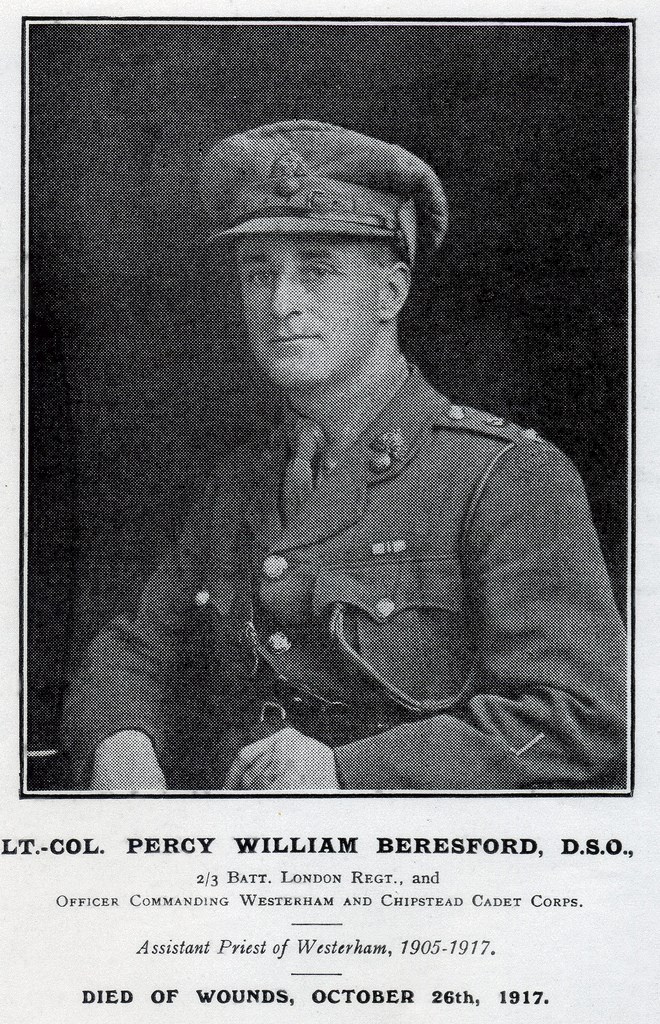

Lt. Col. Percy William Beresford D.S.O

Percy was born in 1875 and was the son of Frank Gilbert and Jessie Ogilvie Beresford. He was baptised 2nd Dec 1875 at St Phillip and St James Church at Whitton near Richmond upon Thames. He was educated at Rossel School and Magdalen College, Oxford.

After graduating from Magdalen College he had hoped to enter the Church, but the ill health of his father, a Wharfinger on the Thames, meant he had to join the family business.

In 1900, he was promoted from Second Lieutenant to Lieutenant whilst he was serving with the 4th Volunteer Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment,

In 1902 he moved to Westerham in Kent where he set up the first parish cadet corps in the country – the Westerham and Chipstead Cadet Corps, which was attached to the 1st Volunteer Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment. He apparently felt that military training acted as a sort of national university.

On the 10th October 1903, The London Gazette announced that Captain R. Galloway resigns his Commission with the 3rd Volunteer Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) and Lieutenant P. W. Beresford to be Captain.

In 1905 he went to Kings College London where he studied Theology, after which his earlier wish was fulfilled, and he was ordained as a Deacon. The following year he was ordained as a Priest by the Bishop of Rochester and was fortunate enough to be appointed as curate to the Rev. Sydney Le Mesurier, vicar of St. Mary’s, Westerham, where he was working when war was declared.

On 1st April 1908 it was announced that Captain Percy William Beresford of the 3rd Volunteer Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) is appointed to the 3rd Battalion, City of London (Royal Fusiliers) Regiment; with rank and precedence as in the Volunteer Force.

In the London Gazette, his promotion from Captain to Major in the 3rd (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) was published on 16th August 1910.

Following the outbreak of World War One, he was initially sent to Malta after which he saw a lot of action across the Channel in France and Flanders. He was wounded in April 1915 and was gassed at Loos in September the same year and allegedly it was reported that, within a week of him being gassed, he was back with his battalion where he officiated at a celebration of Holy Communion, though hardly able to speak.

It was at Bullecourt in March, 1917 where he won his DSO: For conspicuous gallantry and ability in command of his battalion during heavy enemy counter-attacks. The skill with which he handled his reserves was of the utmost assistance to the division on his right, and his determination enabled us to hold on to an almost impossible position. He repulsed three counter-attacks and lost heavily in doing so.

He was killed in action during the 3rd Battle of Ypres on 26th October 1917 whilst commanding the 2nd / 3rd Battalions when a shell burst close beside him and he only lived a few minutes after being hit. He was known to his men in the Royal Fusiliers as “Little Napoleon”.

The Adjutant of his battalion was present when Beresford was mortally wounded gives a graphic picture of the last scene; and so, does Dr. Maude, who was in the same regiment with him. After being hit, he turned to the Adjutant saying, “I’m finished carry on”. A painful pause; then, to the field-doctor who went to see what could be done for him, “I’m finished; don’t bother about me, attend to the others”. A smile lit up his pale, handsome, and still boyish face. “Look after my sister. ..” A longer pause, and, “This is a fine death for a Beresford”, and he was gone.

He is buried in Gwalia Cemetery, Belgium (Near Poperinghe) where upon his gravestone is inscribed the following inscription “HE BRINGETH THEM UNTO THE HAVEN WHERE THEY WOULD BE”. See his CWGC Casualty Record for more information.

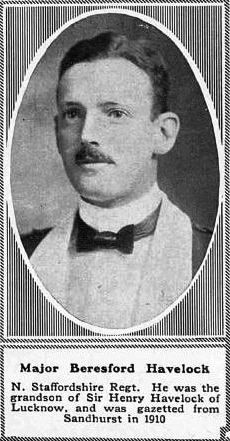

Major Beresford Arthur Jardine-Havelock

He saw action at Neuve Chapelle, Hohenzollern Redoubt. Bullecourt, Ypres & Givenchy, the Duck’s Bill, and Poelcapelle and on the 23rd May 1916 was appointed as an acting Lt. Col of 2nd/3rd Royal Fusiliers.

He was born on the 10th October 1889 in Bankura, India and was the son of George Broadfoot Havelock, late Bengal Police, and Annie Helen Beresford. He married Kathleen Margaret Smith on the 6th March 1916 and they had two children Patricia Margaret Helen and Beresford Aileen.

He joined Elizabeth College on the island of Guernsey in 1903, becoming a member of their Dramatic Society in 1904 and a prefect in 1906. He left in Dec.1906 when he went to the military college at Sandhurst, leaving in 1907.

He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion (Prince of Wales) 98th. North Staffordshire Regiment on 6th February 1909. Just over a year later he was promoted to Lieutenant on the 1st April 1910, (Army List), followed by Captain in 1915 then Major in 1917.

He was serving with the 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment in Mesopotamia from 1914 – 1918. After Mesopotamia, he was sent to Baku, Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea, most probably as part of the Dunsterforce “Hush Hush Army” to help support the City of Baku. Dunsterforce was named after General Lionel Dunsterville and consisted of about 1000 men and undertook a 220 miles journey in a convoy of Ford vans and cars from Hamadan near Quajar in Iran to Baku in Azerbaijan.

The Dunsterforce fought in the Battle of Baku from 26th August to 14th September 1918 between the Ottoman–Azerbaijani coalition forces led by Nuri Pasha and Bolshevik–Dashnak Baku Soviet forces, later succeeded by the British–Armenian–White Russian forces.

The Dunsterforce received orders to leave Baku as the Ottoman forces were bombarding the port and shipping with artillery fire. Two ships had been readied in the port for the evacuation of the force. Major Havelock and his unit, the 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, were providing rear-guard cover during the night of the 14th/15th September allowing the main force to retreat to the port when he was killed on the 14th September 1918 aged 28. He was mentioned in dispatches and is commemorated on the Baku Memorial.

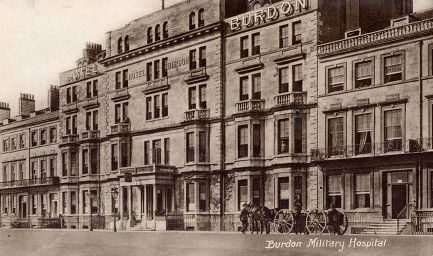

Major Cecil William Beresford

Cecil was born in 1875 and was the son of a Barrister of Law, Cecil Hugh Wriothesley Beresford and his wife Caroline Felicie Octavia. He was baptised on 24th June 1875 at the Holy Innocents Church, Kingsbury in Middlesex.

On the 10th December 1892, the South Wales Daily News announced his Commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Volunteer Rifles the 1st (Pembrokeshire) Volunteer Battalion of the Welsh Regiment.

He was educated at Trinity Hall Cambridge University entering the college in 1895.

The London Gazette published on 14th October 1910 announced the promotion of 2nd Lieutenant Cecil Beresford to Lieutenant with the 10th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Irish Rifles).

His promotion from Lieutenant to Captain was announced on the 26th July 1912 in the London Gazette, along with his transfer from the 10th Bn to the 18th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Paddington Rifles).

He was subsequently promoted from Captain to Major remaining with the 18th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Paddington Rifles) which was announced in the London Gazette on the 6th April 1915. A few months later the Gazette announced his promotion to Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel on the 19th July 1915.

On the 10th April 1916, the London Gazette announced that he relinquished his rank as Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel due to an alteration in posting. It is not clear what happened next in his military career, but when he died, he was serving with the Royal Defence Corps (RDC).

The RDC was formed in March 1916 by converting the Home Service Garrison Battalions which were made up of soldiers that were either too old or medically unfit for front line service. The role of the RDC was to provide troops for security and guard duties inside the UK, guarding important locations such as ports or bridges and prisoner of war camps.

He died of wounds on 9th October 1917 at Burdon Military Hospital Weymouth and is buried at Weston Super Mare.

See his CWGC Casualty Record for more information.

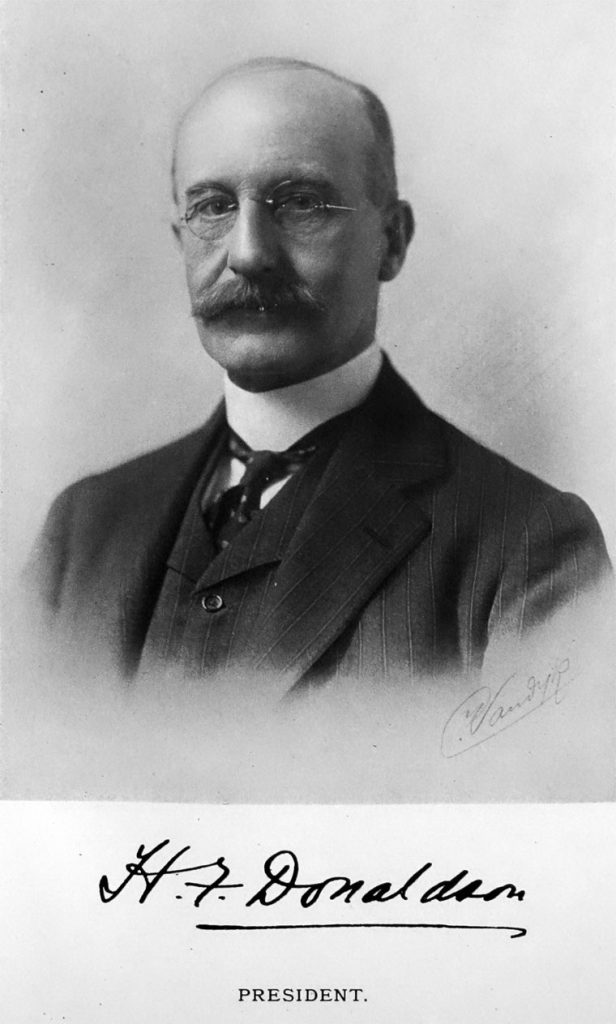

Brigadier General Sir Hay Frederick Donaldson KCB

Hay Frederick Donaldson was born on 7th July 1856 in Sydney Australia and was the son of Sir Stuart Alexander Donaldson, the first Premier of New South Wales, and his wife Amelia Cowper.

Although he was born in Australia, he studied mechanical engineering at Eton College, Trinity College, Cambridge, University of Edinburgh and Zurich University.

After leaving University, he was initially employed at the locomotive works at Crewe in Cheshire working for the London and North Western Railway locomotive works.

He married Selina Beresford on 15 July 1884 in Kensington shortly before moving to Goa in India working on railway and harbour construction until 1887. Whilst in India, the couple had 3 children: Amy Elizabeth, Stuart Hay Marcus and Ethel Adeline.

After India, he returned to England working on the Manchester Ship Canal from 1887 to 1891 followed by becoming the Chief Engineer at London’s East India Docks from 1892 to 1897.

At the same time as working on the Manchester Ship Canal and the East India Docks, he was also the Chief Mechanical Engineer at the Royal Ordnance Factories at Woolwich from 1889 to 1903. Whilst at Woolwich, he served as the Deputy Director-General from 1989-99. In 1903 he was appointed Director-General, a role in which he continued until 1915.

In 1909, he was awarded a CB, Companion to The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, followed by the KCB (Knight Commander) in 1911.

In September 1915, he resigned from the position of Director-General to take up the role of Chief Technical Advisor to the Ministry of Munitions

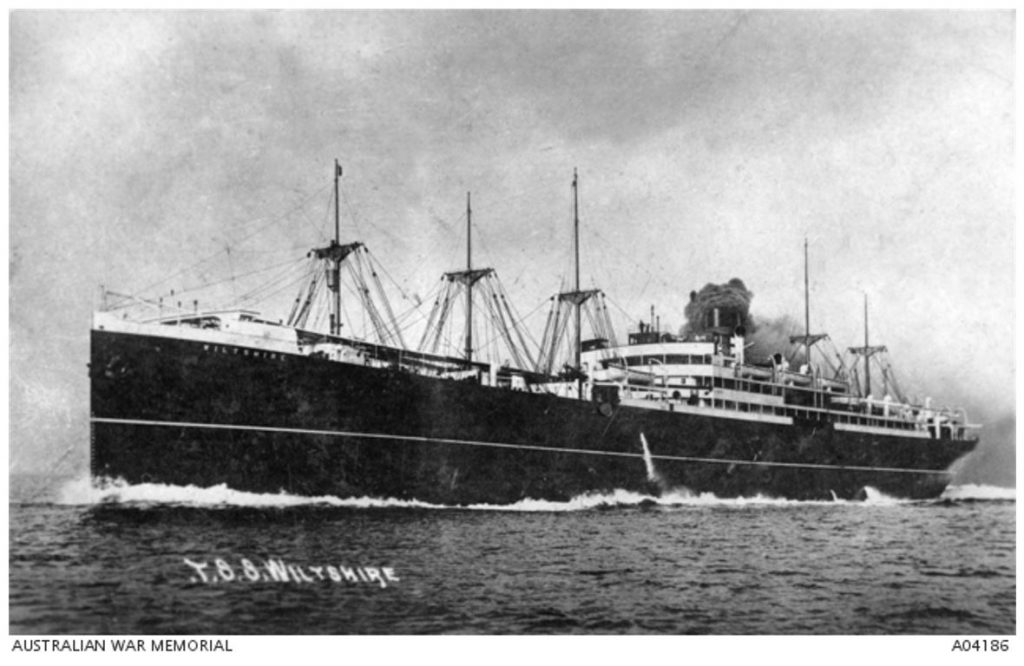

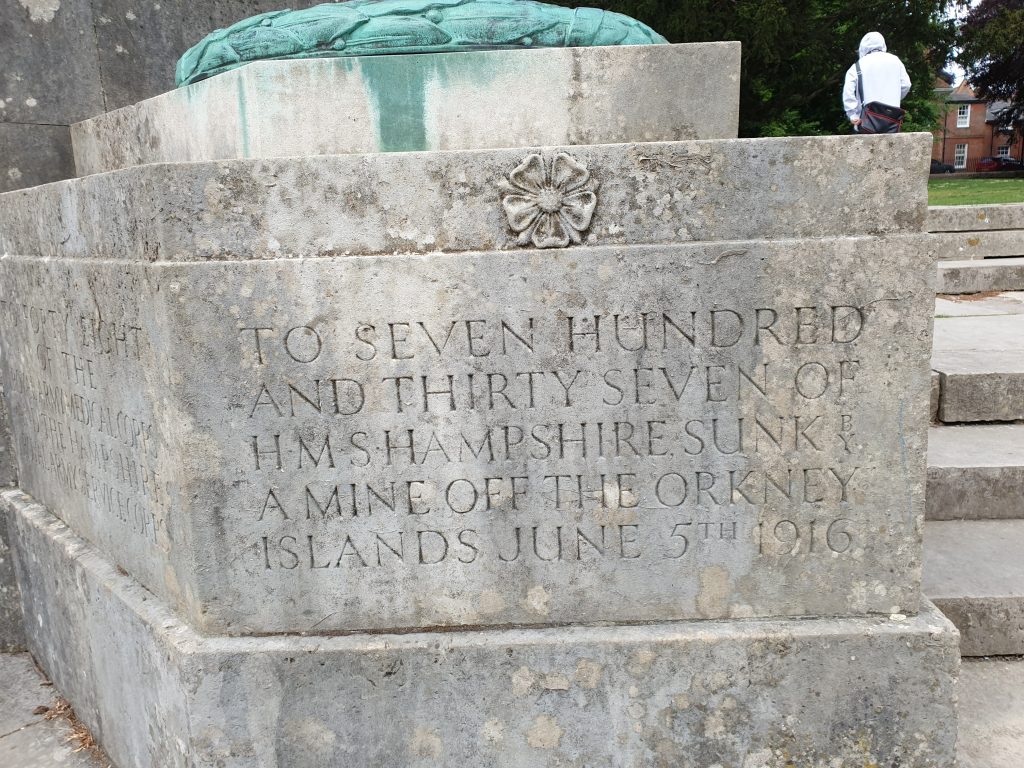

In June 1916, he was selected as one of the advisers to accompany the Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener on his mission to Russia. HMS Hampshire had been ordered to take Lord Kitchener from Scapa Flow on his diplomatic mission to Russia via the port of Arkhangelsk.

The Hampshire set sail from Scapa Flow at 16:45Hrs on the 5th June 1916 and due to gale force winds, it was decided that she would sail through the Pentland Firth, then turn North along the western coast of the Orkneys. Approximately an hour after setting sail, she rendezvoused with her escorts, two Acasta class destroyers, the Unity and Victor.

As the convoy turned North west, the gales increased and shifted direction resulting in the ships facing it head on, causing the escorts to fall behind the Hampshire. The Commanding Officer of the Hampshire, Captain Savill, believed it was unlikely that enemy submarines would be active in the area due t the weather conditions, so he ordered Unity and Victor to return to Scapa Flow.

About 1.5 miles off Orkney, between the Brough of Birsay and Marwick Head, the Hampshire was sailing alone in rough seas when at 19:40Hrs she struck a mine laid by a German minelaying submarine. The mine was one of several laid by U-75 just before the Battle of Jutland on the 28th/29th May.

The Hampshire had been holed between the bow and the bridge, causing her to heel to starboard. Approximately 15 minutes after the explosion, the Hampshire began to sink bow first. Out of the crews compliment of 735 crew members and 14 passengers aboard, only 12 crew members survived. A total of 737 lives were lost including Lord Kitchener and all the members of his missionary party. He is commemorated on the CWGC Hollybrook Memorial at Southampton.

The ships crew are also commemorated on the Hampshire, Isle of Wight and Winchester War Memorial outside Winchester Cathedral.

In 2010, the War Memorials Trust gave a grant of £150 for conservation works to the memorial window and its ferramenta. On the Beresford window at Hoby, the ferramenta had rusted and this was causing problems to the stonework of the church on the window which the ferramenta is fixed to and if left untreated could cause damage and cracking to stonework. To see more information about this grant, see the grant showcase.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.